Rapid and Continuous Production of LiFePO4/C Nanoparticles in Super Heated Water*

YU Wenli (于文利), ZHAO Yaping (赵亚平),** and RAO Qunli (饶群力)

Rapid and Continuous Production of LiFePO4/C Nanoparticles in Super Heated Water*

YU Wenli (于文利)1, ZHAO Yaping (赵亚平)1,** and RAO Qunli (饶群力)2

1School of Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China2Instrumental Analysis Centre, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China

LiFePO4/C, nanoparticle, super heated water

1 INTRODUCTION

Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) is a cathode material for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries [1]. Because of its favorable electrochemical properties, relatively low cost, low toxicity, and high safety, this material is regarded as the substitute for LiCoO2used in commercial Li-ion batteries to power portable electronic products and hybrid electrical vehicles.

However, LiFePO4has its intrinsic disadvantages including low electronic conductivity and low lithium ions diffusivity, which make it difficult to make full use of it in lithium-ion batteries. To overcome these disadvantages, some measures including reduction of particle size and carbon coating have been proposed. It has been observed that the electronic conductivity of LiFePO4can be enhanced significantly by either reducing their particle size or by surface coating LiFePO4particles with thin layers of carbon (LiFePO4/C) [2-7].

As for the synthesis of LiFePO4, the traditional methods were solid phase synthesis [8], co-precipitations [9], emulsion-drying [10], and hydrothermal synthesis [5],., which usually take several steps or several hours’ heat-treatment under high temperature in inert gases or used costly metal-organic compounds as reagents, making the production process time-consuming, energy-hungry, and costly.

Super heated (sub-, super-critical) water [11] has recently gained great interest as a green and controllable media for synthesis of inorganic nano-particles. Because of its rapid mass transfer rate in a single phase, it provides a rapid mixing, nucleation and crystallization environment within a sealed (or continuous flow) reactor, integrating traditional mixing of inorganic salts, precipitation, nucleation, and crystallization processes into one rapid and continuous process. Teja. [12, 13] produced the nanoparticles of LiFePO4in sub- and super-critical water with a batch-type and continuous type reactor. It has been reported [14] that the carbon-coating LiFePO4/C nanoparticles displayed much higher electrochemical performance than pure LiFePO4. But no one attempted to prepare LiFePO4/C nanoparticles in super heated water, to our knowledge.

The main purpose of this article is to report a rapid and continuous production method for LiFePO4/C nanoparticles in super heated water.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 Reagents

Water-soluble starch, ferrous sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O), lithium hydroxide (LiOH), phosphoric acid (-H3PO4), ammonia (NH3), and vitamin C were analytical grade and bought from Shanghai Chemcial Co. No.1, Shanghai, China.

2.2 Experimental procedure

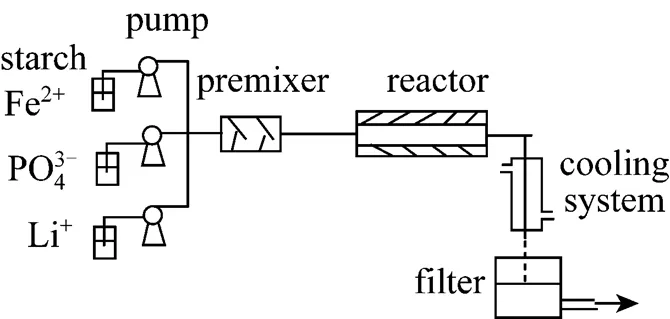

Figure 1 Continuous tubular reactor

2.3 XRD analysis

The particles obtained in the experiments were characterized by a Philips powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with a Cu Kαradiation source (Model PW 1800, Phillips, MA, USA).

2.4 TEM analysis

The morphology of the particles was investigated using a transmission electronic microscope (TEM, JEM-2010/INCA OXFORD). The particles was re-dispersed in ethanol and cast in copper mesh with carbon film before TEM observation. The particle size of every sample was analyzed by using the TEM pictures with software image pro plus 6.0.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 Experimental design

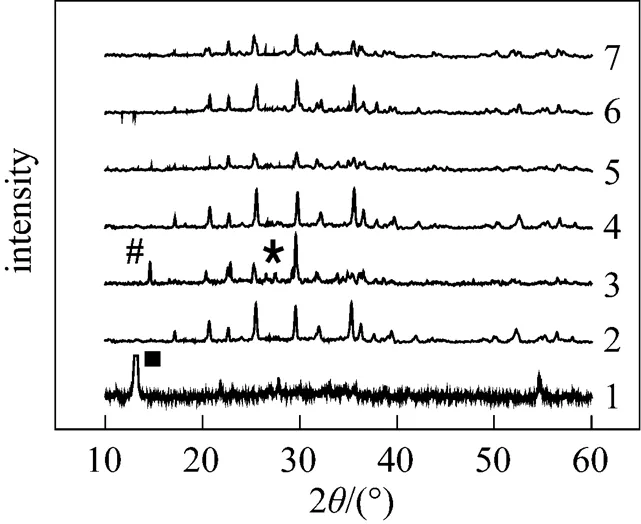

When pH is equal to 5.5, the diffraction peaks could be ascribed to Fe3(PO4)2·8H2O or Fe3(PO4)2[Fig. 2 (1)], that is, the step (2) couldn’t happen in acidic condition; when pH is equal to 9, the diffraction peaks could be ascribed to the mixture of LiFePO4, Fe3(PO4)2, and Fe3(PO4)2(OH)2. The Fe3(PO4)2(OH)2was thought to be the reaction result between excessive OH-with Fe3(PO4)2.

Figure 2 XRD patterns of samples in Table 1

The carbonization of organic substances into carbon materials in aqueous solution has widely been reported [15]. In our preliminary experiments, we found that the soluble starch could be carbonized into carbon materials in super heated water. In this article, we chose soluble starch as carbon precursor to make LiFePO4/C material. Fig. 3 shows the TEM photos of samples listed in Table 1. It could be found that the LiFePO4/C occurred as particles with less than 200 nm size, and LiFePO4was covered by a carbon layer; and the existence of carbon, oxygen, iron, and phosphorus in sample 2 was confirmed by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (Fig. 4) and the carbon layer could be directly observed in the enlarged photo of 2. As it is known that soluble starch is a kind of linear macromolecules composed of a number of glucose units with-1-4 linkages (Fig. 5), having many hydroxyl groups. The starch molecules could chemically bond on the surface of the resultant LiFePO4particlesits hydroxyl groups, and then, carbonize on the surface by dehydration and deoxygenation in super heated water. But the detailed mechanism here should be explored further.

The investigations on the effects of flow rate, temperature, and pressure on the mean particle size (mPS) of LiFePO4/C are shown in Fig. 6. It could be found that the flow rate was a significant factor on the mPS of resultant particles. Higher flow rate led to smaller mPS by comparing samples 2, 4 and 5. The reason might be because of the shorter residence time in reactor at higher flow rate, thus, avoiding the aggregation of particles under excessive heating. This result was consistent with the fact that higher temperature led to larger mPS obtained by comparing samples 2 and 7. In addition, the pressure also played an important role on the mPS of the resultant particles. Higher pressure led to smaller particles by comparing samples 2 and 6, which could be explained by the rapid nucleation of LiFePO4in higher pressure.

Figure 3 TEM photos of LiFePO4/C samples obtained in super heated water

Figure 4 EDS spectrum of LiFePO4/C

Figure 5 Molecular formula of soluble starch

Figure 6 Variation of mean particle size for samples listed in Table 1

1 Padhi, A.K., Nanjundaswamy, K.S., Goodenough, J.B., “Phosphoolivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries”,..., 144, 1188-1194 (1997).

2 Fey, G.T.K., Lu, T.L., “Morphological characterization of LiFePO4/C composite cathode materials synthesizeda carboxylic acid route”,., 178, 807-814 (2008).

3 Zaghib, K., Striebel, K., Guerfi, A., Shim, J., Armand, M., Gauthier, M., “LiFePO4/polymer/natural graphite: low cost Li-ion batteries”,., 50, 263-270 (2004).

4 Bewlay, S.L., Konstantinov, K., Wang, G.X., Dou, S.X., Liu, H.K., “Conductivity improvements to spray-produced LiFePO4by addition of a carbon source”,.., 58, 1788-1791 (2004).

5 Yang, S., Song, Y., Zavalij, P.Y., Whittingham, M.S., “Hydrothermal synthesis of lithium iron phosphate cathodes”,..,3, 505-508 (2001).

6 Huang, H., Yin, S.C., Nazar, L.F., “Approaching theoretical capacity of LiFePO4at room temperature at high rates”,.-., 4, A170-A172 (2001).

7 Franger, S., Le Cras, F., Bourbon, C., Rouault, H., “LiFePO4synthesis routes for enhanced electrochemical performance”,.-., 5, A231-A233 (2002).

8 Uematsu, K., Ochiai, A., Toda, K., Sato, M., “Solid chemical reaction by microwave heating for the synthesis of LiFePO4cathode material”,...., 115, 450-454 (2007).

9 Arnold, G., Garche, J., Hemmer, R., Strobele, S., Vogler, C., Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M., “Fine-particle lithium iron phosphate LiFePO4synthesized by a new low-cost aqueous precipitation technique”,., 119, 247-251(2003).

10 Cho, T.H., Chung, H.T., “Synthesis of olivine-type LiFePO4by emulsion-drying method”,., 133, 272-276 (2004).

11 Hao, Y., Teja, A.S., “Continuous hydrothermal crystallization of Fe2O3and Co3O4nanoparticles”,..., 18, 415-422 (2003).

12 Lee, J., Teja, A.S., “Synthesis of LiFePO4micro and nanoparticles in super heated water”,.., 60, 2105-2109 (2006).

13 Xu, C.B., Lee, J., Teja, A.S., “Continuous hydrothermal synthesis of lithium iron phosphate particles in subcritical and super heated water”,.., 44, 92-97 (2008).

14 Gao, F., Tang, Z.Y., Xue, J.J., “Preparation and characterization of nano-particle LiFePO4and LiFePO4/C by spray-drying and post-annealing method”,, 53, 1939-1944 (2007).

15 Mochidzuki, K., Sato, N., Sakoda, A., “Production and characterization of carbonaceous adsorbents from biomass wastes by aqueous phase carbonization”,, 11, 669-673 (2005).

2008-03-05,

2008-07-18.

Shanghai Special Foundation on Nanomaterials (0243nm305).

** To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: ypzhao@sjtu.edu.cn

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2009年1期

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2009年1期

- Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering的其它文章

- Modeling and Optimization for Scheduling of Chemical Batch Processes*

- Simulation of Droplet-gas Flow in the Effervescent Atomization Spray with an Impinging Plate*

- Numerical Investigation of Constructal Distributors with Different Configurations*

- The Kinetics of the Esterification of Free Fatty Acids in Waste Cooking Oil Using Fe2(SO4)3/C Catalyst

- Multiple Model Soft Sensor Based on Affinity Propagation, Gaussian Process and Bayesian Committee Machine*

- Measurement and Correlation of Solid-Liquid Equilibria of Phenyl Salicylate with C4 Alcohols