几种冷冻稀释液与单胺类防冻剂对中缅树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响

平述煌, 王彩云, 唐文如, 罗 瑛, 杨世华

(昆明理工大学 生命科学与技术学院衰老与肿瘤分子遗传学实验室, 云南 昆明 650500)

几种冷冻稀释液与单胺类防冻剂对中缅树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响

平述煌, 王彩云, 唐文如, 罗 瑛, 杨世华*

(昆明理工大学 生命科学与技术学院衰老与肿瘤分子遗传学实验室,云南 昆明650500)

该文实验精子采自昆明地区经笼养驯化的树鼩(Tupaia belangeri), 检测其冷冻前后运动度、顶体完整率以及检测部分冷冻精子的受精能力。实验一:选用8种已报道的冷冻稀释液TTE、TCG、TCF、TTG、BWW、BTS、DM、SR稀释鲜精,并添加0.4 mol/L DMSO,4℃预冷平衡2h后,TTE、DM和SR稀释液的精子的运动度与鲜精无差别(P>0.05),其余处理组均显著下降(P<0.05)。冷冻复苏后,各组的运动度显著低于预冷平衡处理后的运动度(P<0.05);DM组的复苏运动度显著高于其他稀释液组(P<0.05),BWW组最低(P<0.05)。对于顶体完整率,与鲜精相比,4℃平衡2h后,TTE和DM组精子的顶体完整率显著高于BWW、BTS和SR组(P<0.05)。冷冻复苏后,DM组精子的顶体完整率显著高于其它(除了TTE)冷冻组(P<0.05)。实验二:在DM稀释液基础上分别添加4种浓度0.2、0.4、0.8和1.2 mol/L的二甲基甲酰胺(DF)、甲酰胺(F)、二甲乙酰胺(DA)和乙酰胺(A)以及0.4 mol/L DMSO,经过预冷平衡处理后,与鲜精相比,各防冻剂组的精子运动度没有下降(P>0.05);冷冻解冻后,各冷冻组精子的运动度显著低于预冷平衡处理后的精子运动度(P<0.05);0.8 mol/L DF和0.4 mol/L DMSO组精子的运动度显著高于其它冷冻组(P<0.05)。对于顶体完整率,预冷平衡处理后各高浓度组的比率显著下降;冷冻复苏后,0.4 mol/L F 和0.4 mol/L DF组精子的顶体完整率相对较高。实验三,人工授精实验中,DM+0.8 mol/L DF冷冻精子的受精率为16.7%,DM+0.4 mol/L DMSO的受精率为50.0%。以上实验结果提示,含卵黄的非离子冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻保护效果好,但单胺类防冻剂的防冻效果还需进一步深入研究。

树鼩; 精子冷冻保存; 冷冻稀释液; 单胺类防冻剂

树鼩具有许多灵长类动物的特征(Poonkhum et al, 2000), 被广泛应用于生物医学研究中, 如神经生物学(Remple et al, 2007)、人类病毒性肝炎(Xu et al, 2007; Li et al, 2009)、视觉系统发育(Poveda & Kretz , 2009)、群体社会阶层应激(Kozicz et al, 2008; Zambello et al, 2010)、生殖和发育生物学(Collins et al, 2007)等。不仅如此, 它的体型小, 世代周期短、繁殖效率高, 将会越来越多地应用于生物医学研究领域。由于树鼩具有比较丰富的遗传多样性(Chen et al, 2011), 精子冷冻能够经济、有效地保存有价值的遗传资源, 但到目前为止, 仅有一篇文献报道了冷冻降温速率、冷冻平衡时间和冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响(Ping et al, 2011), 而其他冷冻稀释液和冷冻剂对树鼩精子的冷冻影响以及能否提高冷冻存活率还有待研究。

冷冻稀释液是影响精子冷冻存活率和受精能力的一个重要因素, 而关于树鼩精子冷冻稀释液的选择, 仅有一篇文献比较了基于Tris-TES的两种冷冻稀释液——TTE和TEST对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响(Ping et al, 2011)。然而, 已经有很多种稀释液被应用于哺乳动物精子冷冻保存中, 如基于Tris-TES的TTE和TTG分别用于非人灵长类动物和羊的精子冷冻保存 (Si et al, 2000: Li et al, 2005);基于Tris-Citric acid的TCG和TCF稀释液用于山羊(Santiago-Moreno et al, 2008)、牛(Rasul et al, 2001)、兔(Moce et al, 2003)和狗(Yildiz et al, 2000)的精子冷冻保存; 基于盐和糖的BWW和BTS稀释液用于人类(Martins et al, 2003)和猪(Yeste et al, 2008) 的精子冷冻保存; 基于Lactose-egg yolk的DM稀释液可用于食蟹猴(Li et al, 2006)的精子冷冻保存, 且可以提供类似于TTE液的冷冻保护作用;基于Skim milk- Raffinose的SR稀释液被广泛用于小鼠(Sztein et al, 2000)精子的冷冻保存。尽管有很多冷冻稀释液被用于哺乳动物精子的冷冻保存, 但仅有为数不多的文献比较了几种冷冻稀释液对灵长类动物精子冷冻保存的影响(Li et al, 2006; Leverage et al,1972; Chen et al, 1994)。同时, 哺乳动物精子冷冻保存的方法多数倾向于经验性和实验性。因此, 有必要比较多种冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻保存的影响, 以便探索适合树鼩精子冷冻保存的冷冻稀释液。

在精子冷冻过程中, 防冻剂是影响精子存活率的另一个重要因素。到目前为止, 甘油(Gly)、乙二醇(EG)、二甲基亚砜(DMSO)和丙二醇(PG)作为常用的渗透性防冻剂被广泛应用于哺乳动物精子的深低温冷冻保存(Si et al, 2004; Fermandez- Santos et al, 2005; Li et al, 2005; Fermandez-Santos et al, 2006; Kashiwazaki et al 2006; Farshad et al, 2009)。在前期的实验中, 通过比较不同浓度的甘油、乙二醇、二甲基亚砜和丙二醇对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响,我们发现TTE+0.4 mol/L DMSO 可获得较好的冷冻保护效果(这部分结果已经投稿)。另外, 胺类, 如二甲基甲酰胺、甲酰胺、二甲乙酰胺和乙酰胺等也作为重要的渗透性防冻剂用于哺乳动物精子冷冻保存, 比较二甲基甲酰胺、甲酰胺和甘油对犬精子冷冻保存的效率,表明甲酰胺具有类似甘油的冷冻保护效果(Futino et al, 2010); 比较5%二甲基甲酰胺、5%二甲乙酰胺、5%甲酰胺和3%甘油对野猪精子冷冻保存的效率,表明5%二甲乙酰胺具有最佳的冷冻保存效果(Bianchi et al, 2008); 比较甘油、二甲基亚砜、乳酰胺和乙酰胺对日本兔精子保存存活率的影响, 表明乳酰胺和乙酰胺的冷冻保护效果优于甘油(Kashiwazaki et al, 2006)。由此可见, 胺类可作为渗透性防冻剂被考虑用于哺乳动物的精子冷冻保存。然而, 在树鼩精子的冷冻保存中单胺类防冻剂及其与冷冻稀释液配伍能否产生最佳的冷冻保存效果, 以及冷冻稀释液和防冻剂的冷冻保护作用机制仍不清楚。因此, 本研究目的为选择适用于树鼩精子冷冻保存的最佳冷冻稀释液, 并探讨单胺类防冻剂类型及浓度对树鼩精子冷冻保存的影响。

1 材料与方法

1.1 冷冻液的配制

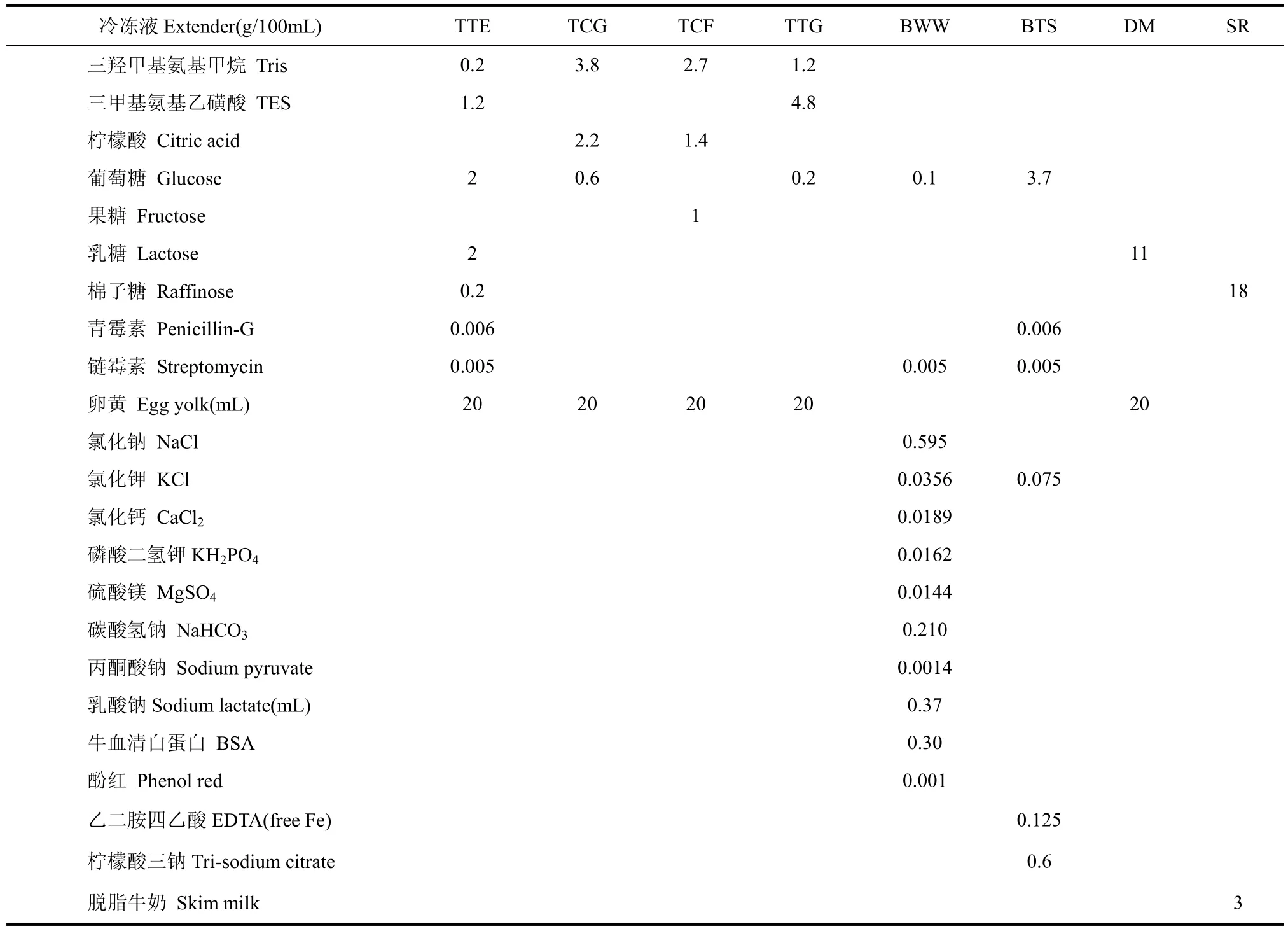

除特殊说明外, 其它所有的化学试剂均购自Sigma公司(St. Louis, MO, USA)。本实验选用8种精子冷冻稀释液, 其组成成分见表1, 配制方法来源于文献报道(Coulter & Foote, 1975; Tateno & Mikamo, 1987; Si et al, 2000; Dube et al, 20024; Li et al, 2005; Kaneko et al, 2006; Santiago-Moreno et al, 2006; Santiago-Moreno et al, 2009)。卵黄均取自于溶液配制当天生产的鸡蛋, 小心敲破蛋壳并去除蛋清,随后用超纯水冲洗完整的卵黄3~5次并用脱脂滤纸吸干卵黄周围的水分, 用10 mL注射器小心刺破卵黄膜并吸取卵黄。将称量好的药品和卵黄溶于超纯水并混匀, 于7 000 r/min,4 ℃离心1 h, 取上清弃沉淀, 并用盐酸或NaOH调上清液pH值至7.0~7.2, 分装于15 mL离心管中储存于-80 ℃冰箱中待用, 其储存期限不超过两周, 使用前于37 ℃水浴中解冻。精子洗涤液为TALP-HEPES, 其配制方法见Bavister et al报道(1983)。分别加入0.2、0.4、0.8和1.2 mol/L的胺类防冻剂(二甲基甲酰胺, dimethyl-formamide, DF; 甲酰胺, formamide, F; 二甲乙酰胺, dimethylacetamide, DA; 乙酰胺, acetamide, A)于选用的冷冻稀释液中, 以配制不同类型、不同浓度防冻剂的冷冻液; 0.4 mol/L DMSO为阳性对照, 不加防冻剂的冷冻液为阴性对照。

表1 8种精子冷冻保存稀释液的组成成分Tab. 1 Components of eight extenders for diluting semen

2.2 实验动物

21只成年雄性树鼩和10只成年雌性树鼩, 体重为110~140 g, 来自昆明医学院, 饲养于昆明理工大学生命科学与技术学院的实验动物房, 饲养时间均不超过2周。所有动物早、中、晚均喂食高压消毒的颗粒饲料, 并补充鸡蛋、牛奶和新鲜水果。动物饲养在100 cm×50cm×40cm(长×宽×高)的笼子中, 单只单笼,室温20~25 ℃, 光照时间为7:00-19:00。所有实验均在5-7月完成。

2.3 精液采集

通过外科手术从睾丸中分离出附睾尾和输精管, 用TLAP-HEPES冲洗离体附睾并小心去除血液和脂肪组织, 随后将附睾尾置于含1 mL 37 ℃TLAP-HEPES的平皿中, 用精细手术剪剪碎附睾尾,继续于37 ℃孵育10 min让精子游离出来。取10 μL精液样品检测精子运动度和顶体完整性, 运动度超过60%的精子样品用于实验。剩余的精子样品用1 mL TLAP-HEPES洗2次, 250 r/min离心4 min。弃上清液, 并立即将精子沉淀用冷冻稀释液稀释混匀,室温维持10 min。

2.4 实验设计

2.4.1 实验一:不同冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响 来自6只雄性树鼩的每份精子样品被均匀分成8等分, 分别用TTE、TCG、TCF、TTG、BWW、BTS、DM、SR冷冻稀释液稀释, 并且将这8份精子冷冻稀释混合液置于4 ℃冰箱中预冷处理2 h, 随后向已经平衡好的精子冷冻稀释混合液中加入0.4 mol/L的DMSO(我们已证实0.4 mol/L DMSO能有效保护树鼩精子, 其结果已经投稿), 继续平衡预冷处理30 min, 取10 μL精子冷冻液检测精子的运动度和顶体完整率, 再将剩余的精子冷冻液分别取150 μL装入冷冻麦管中, 并用热封机封口,每份样品装2管。然后, 将以上的精子冷冻液麦管置于距液氮面4 cm的位置冷冻降温10 min, 最终将所有麦管投入液氮冷冻保存(Ping et al, 2011) 。冷冻保存精子超过3 d后, 直接从液氮中取出并投入37 ℃水浴中复苏2 min, 用TALP-HEPES稀释至1.5 mL, 于250 r/min离心5 min去除防冻液, 取样检测精子运动度和顶体完整性。

2.4.2 实验二:不同渗透性防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响 来自10只雄性树鼩的每份精子样品被均匀分成18等份, 利用实验一选择出的DM冷冻稀释液稀释处理, 然后将这18份含精子冷冻稀释液置于4 ℃冰箱中预冷处理2 h, 随后向已经平衡好的18份精子冷冻稀释液中, 分别加入等体积的含0.4、0.8、1.6和2.4 mol/L的渗透性防冻剂DF、F、DA、A, 以及0.8 mol/L的DMSO、无防冻剂的冷冻稀释液,使得冷冻液中的防冻剂分别为0.2、0.4、0.8和1.2 mol/L的渗透性防冻剂DF、F、DA、A, 以及0.4 mol/L DMSO和无防冻剂的冷冻液, 继续平衡预冷处理30 min, 取10 μL精子冷冻液检测精子运动度和顶体完整率, 再将剩余的精子冷冻液分别取约150 μL装入冷冻麦管中, 并用热封机封口,每份样品装2管。然后, 将以上的精子冷冻液麦管置于距液氮面4 cm的位置冷冻降温10 min, 最终将所有麦管投入液氮冷冻保存。冷冻保存精子超过3 d后, 直接从液氮中取出并投入37 ℃水浴中复苏2 min, 用TALP-HEPES稀释至1.5 mL, 于250 r/min离心5 min去除防冻剂, 取样检测精子运动度和顶体完整性。

2.4.3 实验三:评估冷冻精子的受精能力 来自于5只雄性树鼩的精子被均分两等份,分别配置0.4 mol/L DMSO及0.8 mol/L DF冷冻精液。解冻后的精子分别用1 mL预热的TALP-HEPES复苏, 250 r/min 离心5 min洗两次, 随后用TALP- HEPES将精子稀释到(2.1±0.3)×107/mL活精子的浓度。与此同时, 10只雌性动物进行以下处理:暴露经过诱导排卵处理的雌性树鼩子宫, 将100 μL冷冻精子注射到树鼩的两侧子宫中进行人工授精。其中, 冻存精子的复苏运动度和顶体完整率需分别不低于30%和50%。

对雌性树鼩进行诱导排卵的方法见Coscioni et al(2001)的研究报道, 对雌性树鼩肌肉注射60 IU PMSG, 间隔24 h后分别肌肉注射30 IU PMSG和30 IU HCG。在注射HCG 8 h后, 利用冷冻精子作子宫内人工授精, 步骤如下:利用盐酸氯胺酮(40 mg/kg body weight)对动物进行麻醉处理, 随后将树鼩仰式固定, 刮去腹部的毛, 75%酒精消毒后用已消毒的手术剪刀在腹部正中央打开一个约7 mm的创口, 暴露子宫, 用16#无菌针头在靠近子宫颈且血管分布少的地方刺洞, 接着将直径为0.38 mm并含有100 μL冷冻精子的导管通过洞分别插入到两侧的子宫宫管中, 将精子注射到输卵管的开口附近,最后利用标准的外科手术法缝合伤口并注射5 000 IU的青霉素和止痛药以防止伤口感染和疼痛。待人工授精40 h后, 利用相同的外科手术暴露子宫、输卵管和卵巢, 手术摘除卵巢及其输卵管, 在体视显微镜下利用TALP-HEPES液收集胚胎, 倒置显微镜下观察计数超排卵母细胞和已分裂成2-细胞以上胚胎的数量, 以此计算出受精率, 即受精率=2-细胞以上胚胎数量/总的超排卵母细胞数×100%(Ping et al, 2011)。

2.5 精子功能检测

2.5.1 精子运动度的检测 取10 μL精子混合液(新鲜或预冷处理后或冷冻/解冻后)滴加到已预热至37 ℃的血细胞计数板上, 在光学显微镜下计数向前运动度精子占整个精子群的百分比率, 其操作步骤参考相关Saragusty et al(2009)的研究报道。每次至少计数200个精子, 重复两次。注意:所有样本的运动度评估均由一个熟练的操作者执行; 解冻后的精子运动度应在TALP-HEPES洗涤后, 立即计数运动度;为减少评测的误差, 操作者应盲测所有样本。

2.5.2 顶体完整率检测 采用荧光染料FITC-PNA检测精子的顶体完整率, 其操作见文献报道(Bathgate et al, 2006):将精子样品用TALP-HEPES离心洗2次, 稀释至适当精子浓度, 取20 μL滴在载玻片上, 风干后, 在通风橱中用甲醇溶液固定。待风干后, 加入40 μg/mL的 FITC-PNA与精子样品在37 ℃培养箱中避光孵育30 min, PBS洗去多余的染料, 在荧光显微镜下检查, 其激发光波长和发射光波长分别为490 nm和515 nm, 顶体完整的精子被染成均匀的苹果绿色, 而顶体不完整的精子部分着色或不着色。计数顶体完整和不完整的精子, 每次至少计数200个, 并计算顶体完整率。

2.6 统计分析

所有数据以平均值±标准误(Mean±SE)表示, 精子运动度、运动度复苏率和顶体完整率等百分率数据经过平方根的反正弦转换, 经完全随机设计的单因素方差分析(one way ANOVA)和最小显著差数法(1east significant difference test)检验数据间的差异显著性; 利用Paired-Samplest-test比较鲜精和冷冻精子的受精率;P<0.05为差异显著。以上所有数据的处理及文章中图均通过SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) 软件完成。

3 结 果

3.1 不同冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响

冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻-解冻运动度的影响见表2。相比鲜精而言, 经过预冷平衡处理后, TTE、DM和SR稀释液稀释的精子的运动度未显著性下降(P>0.05), 而其余冷冻稀释液稀释的精子却显著性下降(P<0.05), 且BWW、TTG、BTS组显著低于其他冷冻稀释液组(P<0.05)。冷冻复苏后, 各稀释液组复苏精子的运动度显著低于预冷平衡处理后的运动度(P<0.05); DM组冷冻解冻精子的运动度显著高于其它稀释液冷冻组(P<0.05); TTE和SR组, 显著高于TTG、BWW和BTS组(P<0.05); BWW冷冻组精子的运动度最低(P<0.05)。

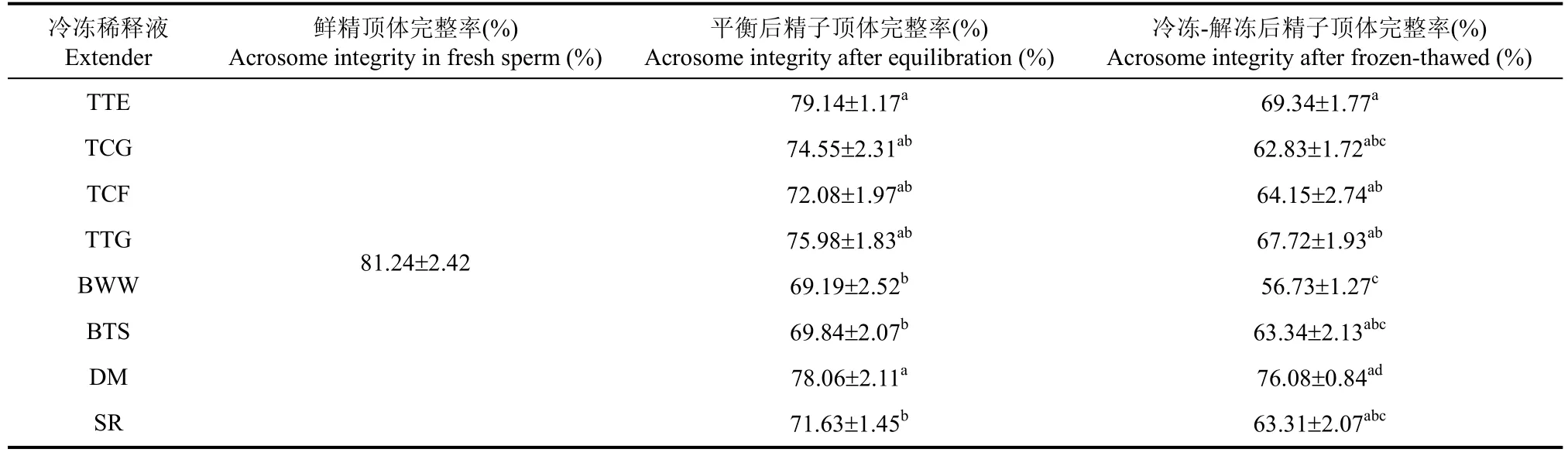

冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻解冻后顶体完整率的影响见表3。相比鲜精, TCF、BWW、BTS和SR组平衡后顶体完整率显著性下降(P<0.05), 而TTE和DM组精子的顶体完整率显著高于BWW、BTS和SR组(P<0.05)。冷冻解冻后, DM组精子的顶体完整率显著高于其他冷冻组(P<0.05), 但与TTE组之间没有显著性差异(P>0.05)。

3.2 不同渗透性防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响

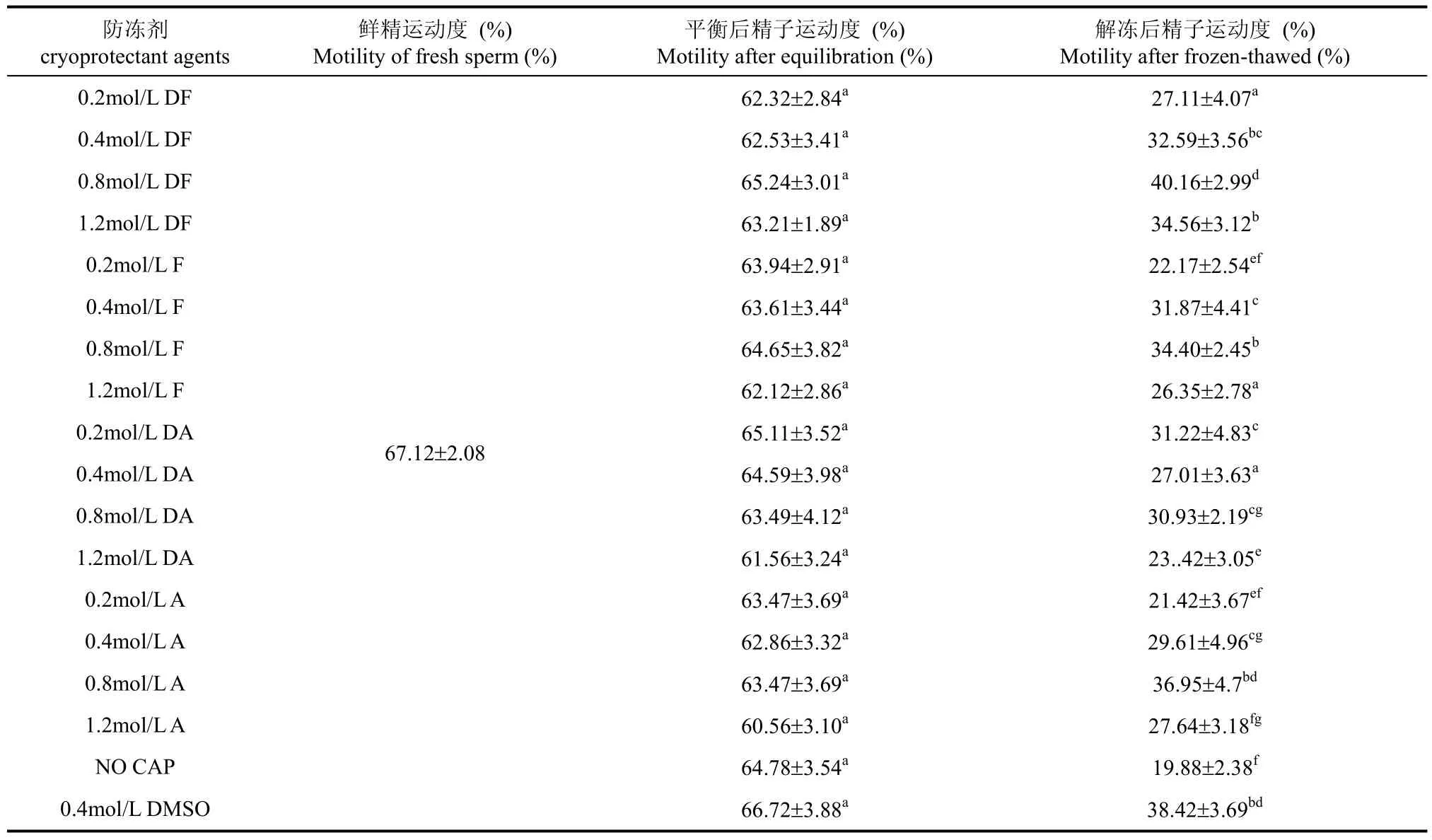

不同防冻剂对树鼩冷冻解冻精子运动度的影响见表4。相比鲜精, 经过预冷平衡处理后, 各防冻剂组的精子运动度未显著性下降(P>0.05)。经过冷冻解冻后, 各组精子的运动度显著低于其预冷平衡处理后的精子运动度(P<0.05); 0.8 mol/L DF组精子的运动度显著高于其它冷冻组, 但与0.8 mol/L A和0.4 mol/L DMSO组之间没有显著性差异(P>0.05)

表2 比较8种不同冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻-解冻运动度的影响(n=6)Tab. 2 Effects of eight extenders on motility during sperm cryopreservation in tree shrews (n=6)

表3 比较8种不同冷冻稀释液对树鼩精子冷冻-解冻顶体完整率的影响Tab. 3 Effects of eight extenders on acrosome integrity in sperm cryopreservation of tree shrews (n=6)

表4 胺类防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻-复苏后精子运动度的影响(n=10)Tab. 4 Effects of monoamines on motility in sperm cryopreservation in tree shrews (n=10)

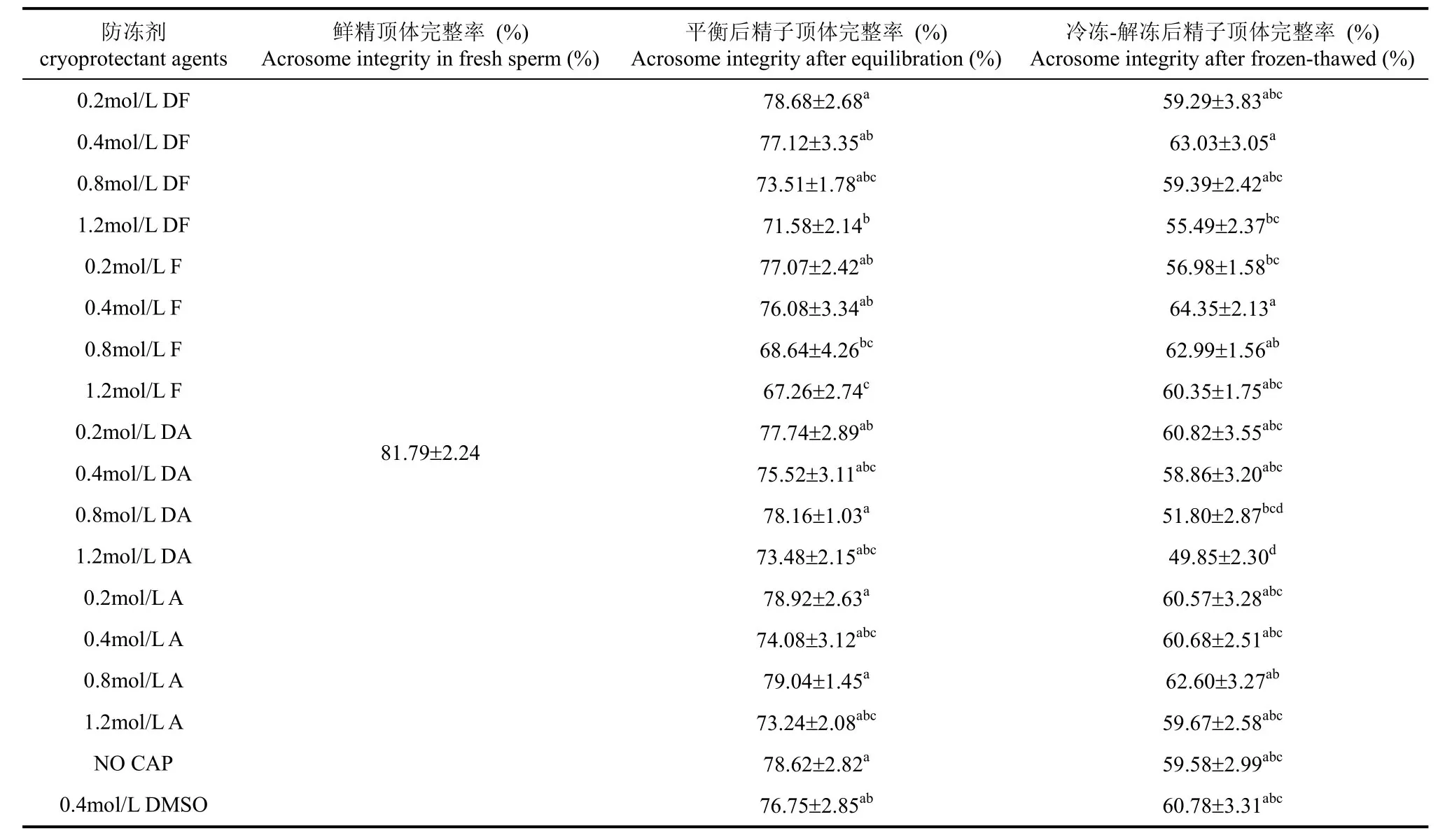

不同防冻剂对树鼩冷冻解冻精子的顶体完整率的影响见表5。经过预冷平衡处理后, 0.2 mol/L DF、0.8 mol/L DA、0.8 mol/L A、0.2 mol/L A和无防冻剂组的顶体完整率显著高于1.2 mol/L DF、0.8 mol/L F和1.2 mol/L F组(P<0.05)。冷冻解冻后, 0.4 mol/L F 和0.4 mol/L DF组精子的顶体完整率显著高于1.2 mol/L DF、0.2 mol/L F、0.8 mol/L DA和1.2 mol/L DA组(P<0.05)。

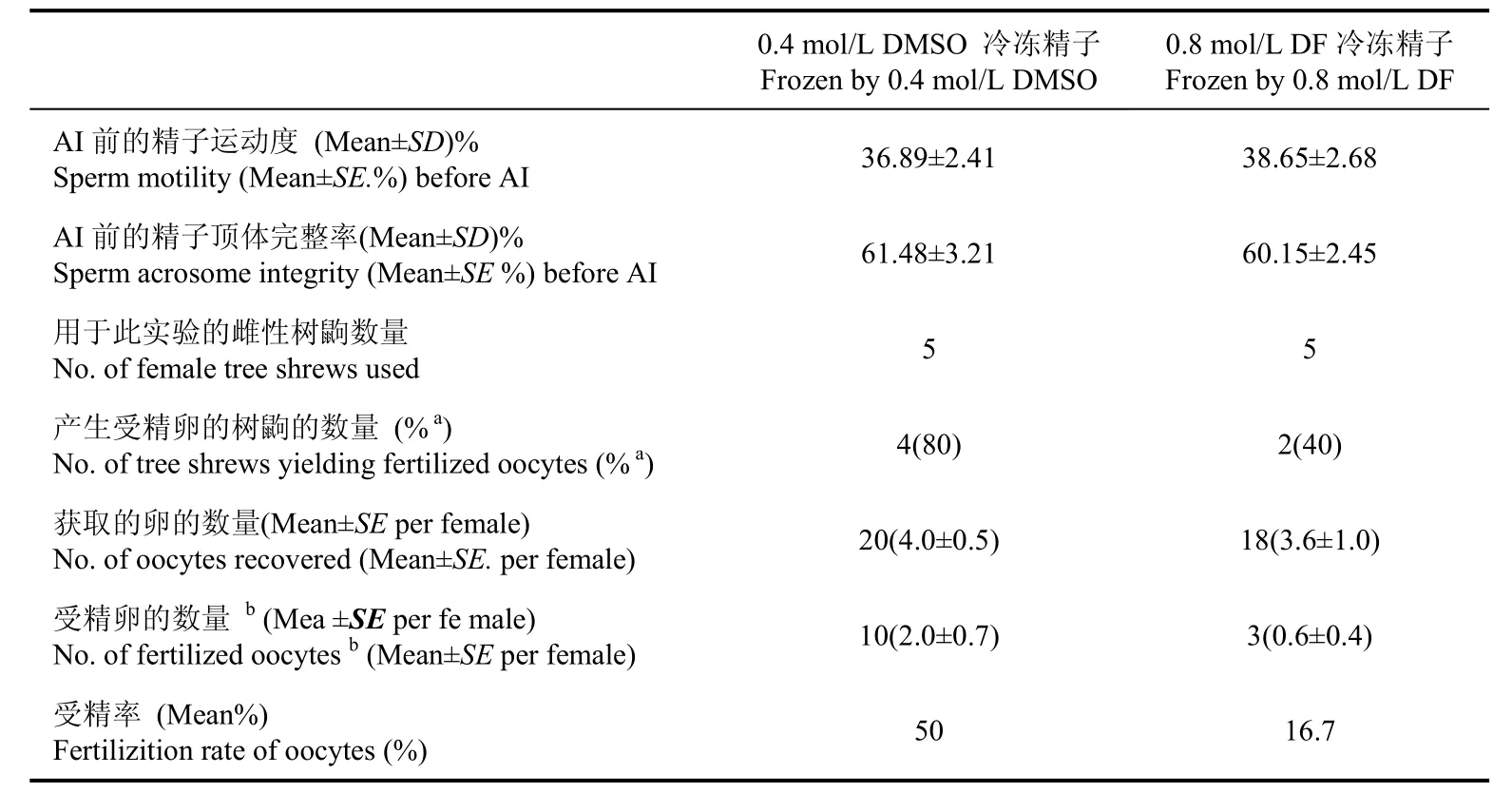

3.3 冷冻精子受精能力的检测结果

如表6所示, 0.8 mol/L DF冷冻精子的受精率(16.7%)与0.4 mol/L DMSO的受精率(50.0%)有显著性差异(P<0.05)。

4 讨 论

本研究首次比较了8种常用冷冻稀释液和4种单胺类渗透性防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响。Ping et al (2011)报道, 适用于树鼩精子冷冻的最佳卵黄浓度、降温速率和冷冻降温平衡时间分别为20%、–172 ℃/min和10 min; 通过比较甘油、乙二醇、二甲基亚砜和丙二醇对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响, 结果表明最佳的防冻剂为0.4 mol/L DMSO,但是仍然存在可提升的冷冻效率空间, 故本次研究在此基础上探讨冷冻稀释液和胺类防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻效率的影响, 以优化树鼩精子冷冻保存方

法。探讨冷冻稀释液和胺类渗透性防冻剂对树鼩这一物种精子的低温生物学特性无疑将有助于提高树鼩精子冷冻保存效率, 为建立一套完整高效可行的低温冷冻方法提供实验依据, 这将有利于提高树鼩在生物医学中的利用率。

表5 防冻剂对树鼩精子冷冻-复苏后精子顶体完整率的影响(n=10)Tab. 5 Effects of monoamines on acrosome integrity in sperm cryopreservation in tree shrews (n=10)

表6 0.8 mol/L DF和0.4 mol/L DMSO冷冻精子的受精能力Tab. 6 Fertilizing ability of tree shrew sperm frozen with 0.8 mol/L DF and 0.4 mol/L DMSO

在精子冷冻保存过程中, 冷冻稀释液成分具有极其重要的作用。这8种冷冻稀释液被广泛应用于哺乳动物的精子冷冻保存过, 并且因物种的不同而冷冻效果不同。比较基于Tris-TES的两种冷冻稀释液(即TTE和TEST)对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响,结果表明, TTE的冷冻保护效果优于TEST, 其原因可能是高浓度的三羟甲基氨基甲烷盐酸(Tris)和三甲基氨基乙磺酸(TES)对树鼩精子造成盐害而受损伤或乳糖和棉子糖给树鼩精子冷冻提供较好的保护作用 (Garde et al, 2008; Ping et al, 2011)。在此8种冷冻稀释液中, TTE和TTG是以Tris-TES为缓冲体系的稀释液, 但TTE的冷冻保护效果优于TTG,其原因可能是TTG中的Tris-TES浓度高于TTE且TTE中的糖浓度和种类多于TTG, 这与Ping et al (2011)报道的结果一致; TCG和TCF是基于Tris-citric acid的稀释液, 虽然TCG的盐浓度高于TCF, 但是冷冻保护效果一样, 其原因可能TCG中Tris的浓度升高不足加剧负面影响; BWW和BTS是基于盐和葡萄糖的两种稀释液, 对树鼩精子的冷冻保护效果最差, 其原因可能是缺少卵黄, 或者盐的存在; DM的主要成分为乳糖和卵黄, 对树鼩精子的冷冻保存效率最高, 与TTE、TTG、TCF、TCG相比, DM稀释液中没有Tris-TES和盐分的存在; SR的主要组成成分为棉子糖和脱脂奶, 但其冷冻保存效率低于DM, 其原因可能是卵黄的冷冻保护效果优于脱脂奶。综上所述, 在树鼩精子冷冻保存过程中, 卵黄是冷冻稀释液中不可缺少的的成分, 但是过多的Tris-TES和金属离子可能易造成树鼩精子冷冻损伤。

在哺乳动物的精子冷冻保存中, 最常用的渗透性防冻剂是甘油, 其次是乙二醇和二甲基亚砜, 胺类防冻剂在犬类 (Futino et al, 2010)、兔 (Kashiwazaki et al, 2006)、羊 (Moustacas et al, 2011)、猪 (Bianchi et al, 2008)、马 (Juliani & Henry, 2008)的精子冷冻保存中作过研究, 但未见到有关胺类防冻剂在灵长类动物精子保存中的研究报道。比较四种不同浓度(0.2、0.4、0.8和1.2 mol/L)的胺类防冻剂(二甲基甲酰胺、甲酰胺、二甲乙酰胺、乙酰胺)对树鼩精子冷冻存活率的影响, 结果表明, 最佳的胺类防冻剂为0.8 mol/L DF, 其冷冻精子运动度和顶体完整率与0.4 mol/L DMSO没有差异, 因此, 0.8 mol/L DF可以替代0.4 mol/L DMSO作为渗透性防冻剂用于树鼩精子冷冻保存。事实上, 运动度和顶体完整率并不是评估冷冻复苏精子功能的最有说服力的指标,而精子受精能力才是衡量精子冷冻是否成功的关键性指标。然而, 具有完整顶体且能运动的精子是人工授精过程中能够受精的必须条件。在哺乳动物中, 许多物种可以利用冷冻精子人工授精产生后代(Gabriel Sanchez-Partida et al, 2000; De Graaf et al, 2010; Underwood et al , 2010), 但是, 冷冻精子受精率和受孕率可能与精子及雌性动物受孕能力有关,如精子冷冻-解冻方法 (O'Meara et al, 2005)、诱导发情同步化的方法、发情的检测、受精时间等 (Anel et al, 2005)。本研究从雌性动物输卵管中获取并计数超排的卵和已经分裂成2-细胞的胚胎, 以受精率来评估冷冻精子的受精能力而不是受孕率。在前期实验中, 我们证明了0.4 mol/L DMSO冷冻精子具有受精能力。因此, 我们比较0.8 mol/L DF 和0.4 mol/L DMSO冷冻精子的受精率。在本研究中, 我们可以从每只雌性动物中获取2~5枚卵或胚胎, 这与Cao et al (2001) 的报道一致。0.8 mol/L DF和0.4 mol/L DMSO冷冻精液受精率分别为16.7%和50%。DF冻精受精能力低下的原因可能是其冻精在移植后存活的时间短或精子内部残存的DF对树鼩受精能力有所影响, 具体原因还有待进一步研究。由此推测, 从人工受精率方面来说, 0.8 mol/L DF应于树鼩精子的冷冻保存还有待进一步研究。

综上所述, 含卵黄的非离子冷冻稀释液可能更有利于树鼩精子冷冻保存, 但单胺类防冻剂的防冻效果还有待进一步证实。

Anel L, Kaabi M, Abroug B, Alvarez M, Anel E, Boixo JC, de la Fuente LF, de Paz P. 2005. Factors influencing the success of vaginal and laparoscopic artificial insemination in churra ewes: a field assay[J]. Theriogenology ,63(4): 1235-1247.

Bathgate R, Maxwell WM, Evans G. 2006. Studies on the effect of supplementing boar semen cryopreservation media with different avian egg yolk types on in vitro post-thaw sperm quality[J]. Reprod Domest Anim,41(1): 68-73.

Bavister BD, Leibfried ML, Lieberman G. 1983. Development of preimplantation embryos of the golden hamster in a defined culture medium[J]. Biol Reprod ,28(1): 235-247.

Bianchi I, Calderam K, Maschio EF, Madeira EM, da Rosa Ulguim R, Corcini CD, Bongalhardo DC, Correa EK, Lucia T Jr, Deschamps JC, Correa MN. 2008. Evaluation of amides and centrifugation temperature in boar semen cryopreservation[J]. Theriogenology,69(5): 632-638.

Cao XM, Ben KL, Wang XL. 2001. Ovulation in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) induced by gonadotrophins[J]. Reprod Fertil Dev,13(5-6): 377-382.

Chen S, Xu L, LüLB, Yao YG. 2011. Genetic diversity and matrilineal structure in Chinese tree shrews inhabiting Kunming, China [J]. Zool Res (in Chinese), 32(1): 17-23.

Collins PM, Tsang WN, Urbanski HF. 2007. Endocrine correlates of reproductive development in the male tree-shrew (Tupaia belangeri) and the effects of infantile exposure to exogenous androgens[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol154(1-3): 22-30.

Coscioni AC, Reichenbach HD, Schwartz J, LaFalci VS, Rodrigues JL, Brandelli A. 2001. Sperm function and production of bovine embryos in vitro after swim-up with different calcium and caffeine concentration[J]. Anim Reprod Sci,67(1-2): 59-67.

Coulter GH, Foote RH. 1975. Lipid deficient extender for bovine spermatozoa: its development and use in measuring freezing-induced lipid loss[J]. J Dairy Sci58(1): 82-87.

De Graaf SP, Evans G, Maxwell WM, Cran DG, O'Brien JK. 2007. Birth of offspring of pre-determined sex after artificial insemination of frozen-thawed, sex-sorted and re-frozen-thawed ram spermatozoa[J]. Theriogenology,67(2): 391-398.

Dube C, Beaulieu M, Reyes-Moreno C, Guillemette C, Bailey JL. 2004. Boar sperm storage capacity of BTS and Androhep Plus: viability, motility, capacitation, and tyrosine phosphorylation[J]. Theriogenology,62(5): 874-886.

Farshad A, Khalili B, Fazeli P. 2009. The effect of different concentrations of glycerol and DMSO on viability of Markhoz goat spermatozoa during different freezing temperatures steps[J]. Pak J Biol Sci,12(3): 239-245.

Fernandez-Santos MR, Esteso MC, Montoro V, Soler AJ, Garde JJ. 2006. Influence of various permeating cryoprotectants on freezability of Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) epididymal spermatozoa: effects of concentration and temperature of addition[J]. J Androl,27(6): 734-745.

Fernandez-Santos MR, Esteso MC, Soler AJ, Montoro V, Garde JJ. 2005. The effects of different cryoprotectants and the temperature of addition on the survival of red deer epididymal spermatozoa[J]. Cryo Letters,26(1): 25-32.

Futino DO, Mendes MC, Matos WN, Mondadori RG, Lucci CM. 2010. Glycerol, methyl-formamide and dimethyl-formamide in canine semen cryopreservation[J]. Reprod Domest Anim,45(2): 214-220.

Gabriel Sanchez-Partida L, Maginnis G, Dominko T, Martinovich C, McVay B, Fanton J, Schatten G. 2000. Live rhesus offspring by artificial insemination using fresh sperm and cryopreserved sperm[J]. Biol Reprod,63(4): 1092-1097.

Garde JJ, del Olmo A, SolerAJ, Espeso G, Gomendio M, Roldan ER. 2008. Effect of egg yolk, cryoprotectant, and various sugars on semen cryopreservation in endangered Cuvier's gazelle (Gazella cuvieri) [J]. Anim Reprod Sci,108(3-4): 384-401.

Juliani GC, Henry M. 2008. Effects of glycerol, ethylene glycol, acetamide, and dried skim milk in cryopreservation of equine sperm[J]. Arq Bras Med Vet Zoo,60(5): 1103-1109.

Kaneko T, Yamamura A, Ide Y, Ogi M, Yanagita T, Nakagata N. 2006. Long-term cryopreservation of mouse sperm[J]. Theriogenology,66(5):1098-1101.

Kashiwazaki N, Okuda Y, Seita Y, Hisamatsu S, Sonoki S, Shino M, Masaoka T, Inomata T. 2006. Comparison of glycerol, lactamide, acetamide and dimethylsulfoxide as cryoprotectants of Japanese white rabbit spermatozoa[J]. J Reprod Dev,52(4): 511-516.

Kozicz T, Bordewin LA, Czeh B, Fuchs E, Roubos EW. 2008. Chronic psychosocial stress affects corticotropin-releasing factor in the paraventricular nucleus and central extended amygdala as well as urocortin 1 in the non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus of the tree shrew[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology ,33(6): 741-754.

Li Y, Wan DF, Wei W, Su JJ, Cao J, Qiu XK, Ou C, Ban KC, Yang C, Yue HF. 2008. Candidate genes responsible for human hepatocellular carcinoma identified from differentially expressed genes in hepatocarcinogenesis of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinesis) [J]. HepatolRes,38(1): 85-95.

Li YH, Cai KJ, Kovacs A, Ji WZ. 2005. Effects of various extenders and permeating cryoprotectants on cryopreservation of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) spermatozoa[J]. J Androl, ,26(3): 387-395.

Li YH, Cai KJ, Li J, Dinnyes A, Ji WZ. 2006. Comparative studies with six extenders for sperm cryopreservation in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) and rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) [J]. Am J Primatol,68(1): 39-49.

Li YH, Cai KJ, Su L, Guan M He XC, Wang H, Kovacs A, Ji WZ 2005. Cryopreservation of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) spermatozoa in a chemically defined extender[J]. Asian J Androl,7(2): 139-144.

Martins SG, Miranda PV, Brandelli A. 2003. Acrosome reaction inhibitor released during in vitro sperm capacitation[J]. Int J Androl,26(5): 296-304.

Moce E, Vicente JS, Lavara R. 2003. Effect of freezing-thawing protocols on the performance of semen from three rabbit lines after artificial insemination[J]. Theriogenology,60(1): 115-123.

Moustacas V, Cruz B, Varago F, Miranda D, Lage P, Henry M. 2011. Extenders containing dimethylformamide associated or not with glycerol are ineffective for ovine sperm cryopreservation[J]. Reprod Domest Anim,46(5): 924-925

O'Meara CM, Hanrahan JP, Donovan A, Fair S, Rizos D, Wade M, Boland MP, Evans AC, P Lonergan. 2005. Relationship between in vitro fertilisation of ewe oocytes and the fertility of ewes following cervical artificial insemination with frozen-thawed ram semen[J]. Theriogenology,64(8): 1797-1808.

Paudel KP, Kumar S, Meu SK, Kumaresan A. 2010. Ascorbic acid, catalase and chlorpromazine reduce cryopreservation-induced damages to crossbred bull spermatozoaa[J]. Reprod Domest Anim,45(2): 256-262.

Ping S, Wang F, Zhang Y, Wu C, Tang W, Luo Y, Yang S. 2011. Cryopreservation of epididymal sperm in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) [J]. Theriogenology,76(1): 39-46.

Poonkhum R, Pongmayteegul S, Meeratana W, Pradidarcheep W, Thongpila S, Mingsakul T, Somana R. 2000. Cerebral microvascular architecture in the common tree shrew (Tupaia glis) revealed by plastic corrosion casts[J]. Microsc Res Tech,50(5): 411-418.

Poveda A , Kretz R. 2009. c-Fos expression in the visual system of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) [J]. J Chem Neuroanat,37(4): 214-228.

Rasul Z, Ahmad N, Anzar M. 2001. Changes in motion characteristics, plasma membrane integrity, and acrosome morphology during cryopreservation of buffalo spermatozoa[J]. J Androl,22(2): 278-283.

Remple MS, Reed JL, Stepniewska I, Lyon DC, Kaas JH. 2007. The organization of frontoparietal cortex in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri): II. Connectional evidence for a frontal-posterior parietal network[J]. J Comp Neurol,501(1): 121-149.

Santiago-Moreno J, Coloma MA, Dorado J, Pulido-Pastor A, Gomez-Guillamon F, Salas-Vega R, Gomez-Brunet A, Lopez-Sebastian A. 2009. Cryopreservation of Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) sperm obtained by electroejaculation outside the rutting season[J]. Theriogenology,71(8): 1253-1260.

Santiago-Moreno J, Coloma MA, Toledano-Diaz A, Gomez-Brunet A, Pulido-Pastor A, Zamora-Soria A, Carrizosa JA, Urrutia B, Lopez-Sebastian A. 2008. A comparison of the protective action of chicken and quail egg yolk in the cryopreservation of Spanish ibex epididymal spermatozoa[J]. Cryobiology,57(1): 25-29.

Santiago-Moreno J, Toledano-Diaz A, Pulido-Pastor A, Dorado J, Gomez-Brunet A, Lopez-Sebastian A. 2006. Effect of egg yolk concentration on cryopreserving Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) epididymal spermatozoa[J]. Theriogenology,66(5): 1219-1226.

Saragusty J, Gacitua H, Rozenboim I, Arav A. 2009. Protective effects of iodixanol during bovine sperm cryopreservation[J]. Theriogenology,71(9): 1425-1432.

Si W, Zheng P, Li YH, Dinnyes A, Ji WZ. 2004. Effect of glycerol and dimethyl sulfoxide on cryopreservation of rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) sperm[J]. Am J Primatol,62(4): 301-306.

Si W, Zheng P, Tang X, He X, Wang H, Bavister BD, Ji W. 2000. Cryopreservation of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) spermatozoa and their functional assessment by in vitro fertilization[J]. Cryobiology,41(3): 232-240.

Sztein JM, Farley JS, Mobraaten LE. 2000. In vitro fertilization with cryopreserved inbred mouse sperm[J]. Biol Reprod,63(6): 1774-1780.

Tateno H, Mikamo K. 1987. A chromosomal method to distinguish between X- and Y-bearing spermatozoa of the bull in zona-free hamster ova[J]. J Reprod Fertil,81(1): 119-125.

Underwood SL, Bathgate R, Maxwell WM, Evans G. 2010. Birth of offspring after artificial insemination of heifers with frozen-thawed, sex-sorted, re-frozen-thawed bull sperm[J]. Anim Reprod Sci,118(2-4): 171-175.

Xu XP, Chen HB, Cao XM, Ben KL. 2007. Efficient infection of tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) with hepatitis C virus grown in cell culture or from patient plasma[J]. J Gen Virol88: 2504-2512.

Yeste M, Briz M, Pinart E, Sancho S, Garcia-Gil N, Badia E, Bassols J, Pruneda A, Bussalleu E, Casas I, Bonet S.2008. Hyaluronic acid delays boar sperm capacitation after 3 days of storage at 15 degrees C[J]. Anim Reprod Sci,109(1-4): 236-250.

Yildiz C, Kaya A, Aksoy M, Tekeli T. 2000. Influence of sugar supplementation of the extender on motility, viability and acrosomal integrity of dog spermatozoa during freezing[J]. Theriogenology ,54(4): 579-585.

Zambello E, Fuchs E, Abumaria N, Rygula R, Domenici E, Caberlotto L. 2010. Chronic psychosocial stress alters NPY system: different effects in rat and tree shrew[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry ,34(1): 122-130.

Effects of some extenders and monoamines on sperm cryopreservation in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri)

PING Shu-Huang, WANG Cai-Yun, TANG Wen-Ru, LUO Ying, YANG Shi-Hua

(Laboratory of Molecular Genetics of Aging and Tumor, Faculty of Life Science and Technology, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650500, China)

The tree shrew may be an important experimental animal for disease models in humans. The effects of some extenders and momamines on sperm cryopreservation will provide helpful data for experimentation of strains and conservation of genetic resources in tree shrews. Epididymal sperm were surgically harvested from male tree shrews captured around Kunming, China and sperm motility, acrosome integrity and fertility were assessed during cryopreservation. In Experiment 1 eight extenders (TTE, TCG, TCF, TTG, BWW, BTS, DM, and SR) supplemented with 0.4 mol/L DMSO were used to dilute the sperm: only TTE, DM and SR showed no differences in motility and acrosome integrity compared to fresh controls after equilibration. After freezing and thawing, sperm in any extender showed lower motility than fresh control and sperm in DM showed higher motility than other groups. However, BWW produced the lowest motility. For acrosome intergrity, TTE and DM showed higher than BWW, BTS and SR after equilibration. The parameter in DM was higher than other groups (except TTE) after thawing. In Experiment 2 four penetrating cryoprotectant agents (CPA) [dimethyl-formamide (DF), formamide (F), dimethylacetamide (DA), and acetamide (A)] at 0.2 mol/L, 0.4 mol/L, 0.8 mol/L, and 1.2 mol/L, respectively were added to the DM extender. Motility showed no difference among CPA groups and non-CPA group (control) after equilibration, but all thawed sperm showed lower values in motility and acrosome intergrity than pre-freezing groups. However, sperm in 0.8 mol/L DF and 0.4 mol/LDMSO showed higher values in both parameters than that in other CPA groups (P>0.05). In Experiment 3 the fertilization rate of oocytes inseminated with 0.4mol/L DMSO (50%) were higher than that with 0.8mol/L DF (16%). In conclusion, non-ion extenders supplemented with egg yolk may be better for sperm cryopreservation in tree shrews and cryoprotectant effects of monoamines agents should be further studied in this species.

Tree shrew; Sperm cryopreservation; Extender; Monoamines

Q954.43; Q959.832; Q492

A

0254-5853-(2012)01-0019-10

10.3724/SP.J.1141.2012.01019

2011-11-01;接受日期:2011-12-28

国家自然科学基金项目(31071279, 31040055);云南省科技创新人才计划项目(2011CI009)资助

∗通信作者(Corresponding author),E-mail: huashiyang@hotmail.com