Dwindling in the mountains: Description of a critically endangered and microendemic Onychodactylus species (Amphibia, Hynobiidae) from the Korean Peninsula

DEAR EDITOR,

Species that are not formally described are generally not targets for conservation, regardless of their threatened status.While habitat degradation has increased over the past several decades in the Republic of Korea, taxonomic and conservation efforts continue to lag. For instance, a clade ofOnychodactylusclawed salamanders from the extreme southeastern tip of the Korean Peninsula, which diverged ca.6.82 million years ago from its sister speciesO. koreanus, is under intense anthropogenic pressure due to its extremely restricted range, despite its candidate species status. Here,using genetics, morphometrics, and landscape modeling, we confirmed the species status of the southeast KoreanOnychodactyluspopulation, and formally described it asOnychodactylus sillanussp. nov. We also determined threats,habitat loss, and risk of extinction based on climatic models under different Representative Concentration Pathways(RCPs) and following the IUCN Red List categories and criteria. Based on several climate change scenarios, we estimated a decline in suitable habitat between 87.6% and 97.3% within the next three generations, sufficient to be considered Critically Endangered according to Category A3 of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. These findings should help enable the development of conservation programs and civic activities to protect the population. Conservation action plans are a priority to coordinate the activities required to protect this species.

Current anthropogenic activities continue to have a tremendous impact on global biodiversity, leading to the world’s sixth mass extinction event (Ceballos et al., 2015).Consequently, biodiversity is reaching a tipping point for future self-sustainment (Rinawati et al., 2013), and conservation efforts are critical for the continuity of natural evolutionary patterns and the avoidance of anthropomorphic selection(Otto, 2018). However, conservation first requires a formal description of the species. This is especially true for highly threatened amphibians (www.iucnredlist.org), where habitat loss is a leading driver of species decline (Lindenmayer &Fischer, 2013). Species protection relies on explicit and recognized taxonomy, much of which is still under consideration in East Asia (Kim et al., 2016; see Supplementary Materials for examples and links between taxonomy and conservation).

Despite recent taxonomic developments in amphibians inhabiting the Republic of Korea (hereafter R. Korea), diversity within the clawed salamander genusOnychodactylus(Caudata, Hynobiidae) remains poorly understood (details on genus taxonomy are provided in the Supplementary Materials). Based on genetic data, two potentially undescribedOnychodactylusspecies exist in R. Korea (Poyarkov et al.,2012; Suk et al., 2018), one from southern Gyeongsang Province (Poyarkov et al., 2012; Suk et al., 2018) and one from Gangwon Province (Suk et al., 2018). The southern Gyeongsang population is increasingly threatened by habitat loss, threats shared with that ofHynobius yangidue to overlapping habitats (Borzée & Min, 2021), and resulting in legal challenges aiming at their protection(https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/34985). With the continuing decline in the genusOnychodactylus(Maslova et al., 2018; Suk et al., 2018; see Supplementary Materials for additional information), the aim of this study was to determine the taxonomic and threat status ofOnychodactyluspopulations in Yangsan and Miryang in southeastern R.Korea.

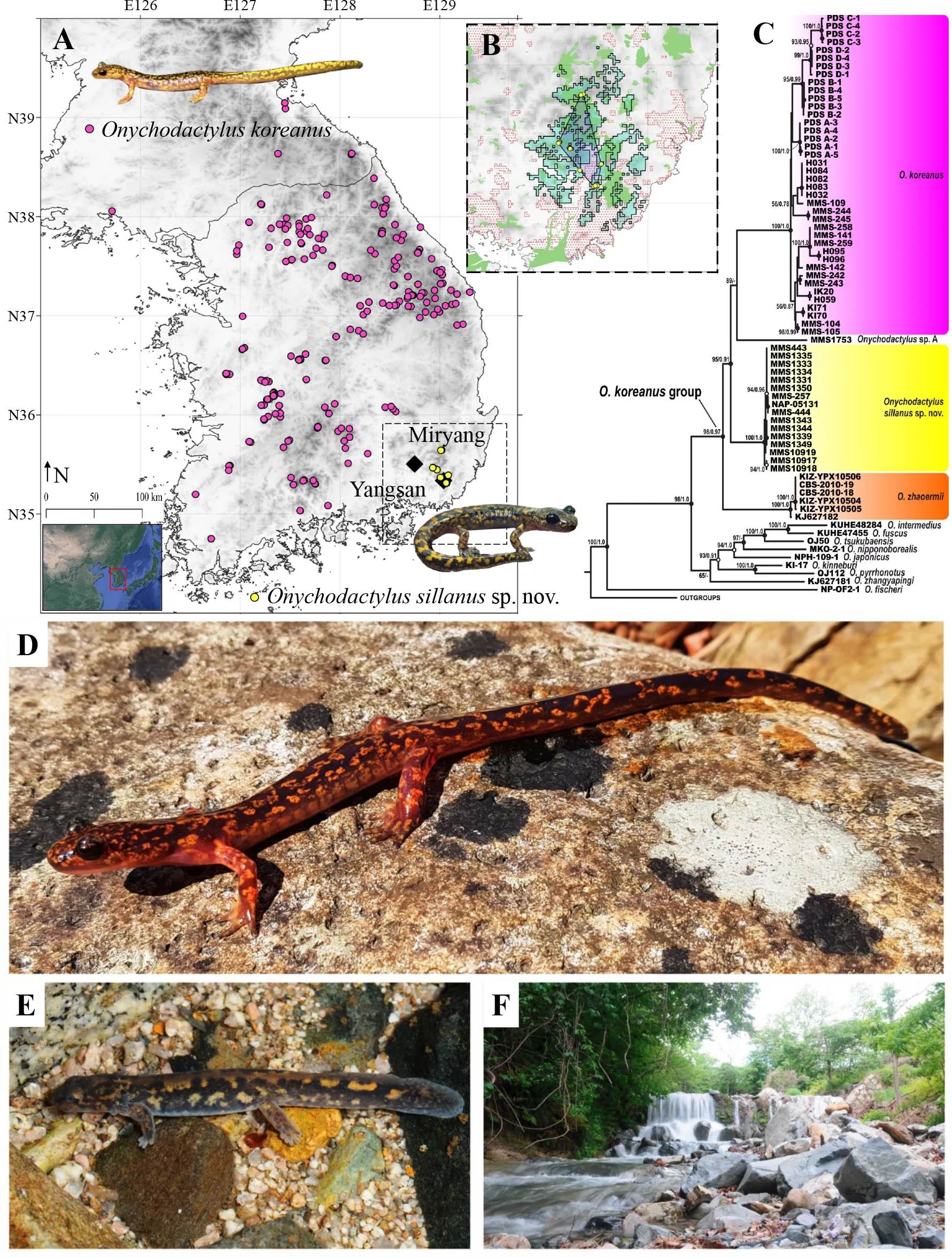

We assessed the taxonomic status of the species using morphological (Supplementary Tables S1, S2) and molecular analyses (Supplementary Table S3). We then determined niche differentiation for the focal clade andO. koreanusthrough ecological niche modeling (ENM; Figure 1). Finally,we modeled the impact of climate change and conducted conservation assessment for the focal clade. All details on study materials and methods are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Morphometric analyses demonstrated significant differences betweenO. koreanusand the candidateOnychodactylusspecies from Yangsan and Miryang. Analysis of variance(ANOVA) used to test for variations between clades based on four principal components (PCs) was significant for PC3(X2=7.52;F(47,48)=8.74,P=0.005; Supplementary Table S2),although only two variables significantly loaded into PC3:length of front and back limbs. The larvae of the candidate species had significantly longer front and back limbs thanO.koreanus(Supplementary Table S4 and Figure S1). However,these variables overlapped between the two clades(Supplementary Table S4). In addition, visual comparison of the vomerine teeth indicated that the candidate species was more similar toO. zhaoermiiin tooth shape, butO. koreanusin tooth number, although we note the small sample size used for comparison (see Supplementary Figure S2). The morphological differences between the two species may be more generalized for adults as morphological divergences in amphibians are generally better understood for adults than for larvae.

For phylogenetic analysis, we obtained a 532 bp long fragment of 16S rRNA, 1 153 bp long fragment of cytb, and 654 bp long fragment ofCOImitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)genes. The final concatenated alignment of mtDNA data was 2 339 bp, and included 1 728 conservative sites, 601 variable sites, and 397 parsimony informative sites within the ingroup(Figure 1). Phylogenetic analyses employing Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum-likelihood (ML) approaches yielded nearly identical topologies, which only differed slightly in associations at several poorly supported nodes (Figure 1).The topology of the matrilineal genealogies withinOnychodactyluswas sufficiently resolved and largely consistent with earlier phylogeny of the genus presented by Poyarkov et al. (2012) and Yoshikawa & Matsui (2013, 2014).Details on the phylogenetic relationships between non-focal clades ofOnychodactylusare presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Within theO. koreanusspecies group inhabiting the Korean Peninsula, three clades with unresolved topological relationships were revealed (Figure 1): (1)O. koreanussensu stricto clade, which included populations from the southwest,north, and northeast of R. Korea (see Figure 1); (2) population from Gangwon Province in the extreme northeast of R. Korea,herein referred to asOnychodactylussp. B; and (3)populations from the extreme southeast of the Korean Peninsula, corresponding to the candidateOnychodactylusspecies from Yangsan and Miryang. Uncorrected geneticPdistances calculated from the cytbgene fragment supported the species level of all three clades within the group(Supplementary Table S5; details in Supplementary Materials). The split between the candidate clade andO.koreanuslikely occurred due to continued tectonic activity following the formation of the Yangsan fault (Suk et al., 2018),a lowland area that does not fit the ecological requirements of either species (see Supplementary Materials for discussion on clade origin).

Our analyses indicated clear differences in potential habitat suitability between the candidate species andO. koreanus.Based on evaluation metrics, the (ENMs) forO. koreanus(AUC=0.886±0.02; TSS=0.626±0.03) and the candidate species (AUC=0.819±0.07; TSS=0.549±0.18) showed good predictive ability. The lower AUC for the candidate species is likely linked to the lower sample size. The additional jackknife test applied to the candidate species also indicated significant predictive ability of the ENM, despite the small sample size(P=0.03). The contributions of environmental variables in the ENMs differed betweenO. koreanusand the candidate species, with slope showing the highest contribution forO.koreanusand mean diurnal range (bio2) showing the highest contribution for the candidate species (Supplementary Table S6; details in Supplementary Materials). In addition, the ENMs for both species were congruent with known distribution(Supplementary Figure S3; details in Supplementary Materials). Of note, while the ENM forO. koreanuspredicted high habitat suitability within the range of the candidate species, without occurring in the area, the ENM for the candidate species provided only weak predictions within theO. koreanusrange (Supplementary Figure S3).

Niche identity analysis indicated that while the ENMs generated forO. koreanusand the candidate species were somewhat similar (Schoener’sD=0.30;I=0.59), they were significantly different (P<0.05). Range break analysis showed no significant differences in the ENMs betweenO. koreanusand the candidate species (PD=0.3663;PI=0.3663). However,comparison betweenO. koreanusand the “ribbon clade” on the Yangsan Fault showed that the ENMs of the two species differed significantly based on theIstatistic (PD=0.059;PI=0.039), while the ENMs of the candidate species and“ribbon clade” differed significantly based on theDstatistic(PD=0.039;PI=0.079). Therefore, the presence of unsuitable habitat between the ranges ofO. koreanusand the candidate species likely acts as a barrier to dispersal, resulting in the isolation of both clades (see Supplementary Materials for additional discussion on “ribbon clade”).

Taxonomic account

Following concordant lines of evidence based on molecular and morphometric analyses of species-level divergence, we hypothesize that the Yangsan-Miryang population ofOnychodactylusrepresents a discretely diagnosable lineage.Its species status should be urgently recognized, as formally described below. The species description presented herein relies on individuals already in collections as the species is threatened and sacrificing additional individuals for formal description contravenes the conservation practices recommended in this work.

Figure 1 Range, suitable habitat, and phylogenetic relationships of Onychodactylus sillanus sp. nov.

Onychodactylus sillanus sp. nov. Min, Borzée, &Poyarkov

Supplementary Figures S2, S4-S6 and Tables S4, S7

Holotype:CGRB15897 (field ID MMS6682) deposited in the Conservation Genome Resources Bank for Korean Wildlife(CGRB), subadult (metamorph, likely female) specimen collected by Mi-Sook Min and Chang Hoon Lee on 13 March 2014 from a montane stream at Sasong-ri, Dong-myeon,Yangsan, Republic of Korea (N35.309659°, E129.067086°;110 m a.s.l.) (Supplementary Figure S5).

Paratypes:Three specimens, including CGRB15898 (field ID MMS6688); juvenile (larval) specimen collected by Mi-Sook Min and Chang Hoon Lee on 24 March 2014 from a montane stream at Sasong-ri, Dong-myeon, Yangsan, Republic of Korea (N35.306060°, E129.074238°; 100 m a.s.l.;Supplementary Figure S2); CGRB15906 (field ID MMS-7207),subadult (metamorph, likely male) specimen collected by Mi-Sook Min and Haejun Baek on 15 May 2015 from a montane stream at Sasong-ri, Dong-myeon, Yangsan, Republic of Korea (N5.31275°, E129.06892°; 110 m a.s.l.; CGRB 15907(field ID MMS 7270 / NAP-05131), subadult (likely male)specimen collected by Mi-Sook Min and Nikolay A. Poyarkov on 5 May 2015 from a montane stream at Unmun Mountain,Unmun-myeon, Unmunsan-gil, Cheongdo-gun, North Gyeongsang Province, Republic of Korea (N35.643892°,E129.018449°; 730 m a.s.l.; Supplementary Figure S6).

Diagnosis:A slender, medium-sized hynobiid salamander and member of the genusOnychodactylusbased on a combination of the following morphological features: lungs absent; black claw-like keratinous structures present on both fore- and hindlimbs in larvae and breeding adults; tail longer than sum of head and body lengths, tail in adults almost cylindrical at base, slightly compressed laterally at distal end;vomerine teeth in transverse row of short arch-shaped series in contact with each other; larvae with skinfolds on posterior edges of both fore- and hindlimbs; breeding males with dermal flaps on posterior edges of hindlimbs; other typical features of genus. The new species can be diagnosed from other members of the genus by the following combination of adult characters: 11-12 costal grooves; vomerine teeth in two comparatively shallow, slightly curved series with 18-22 teeth in each, in contact medially; outer branches of vomerine tooth series slightly longer than inner branches and outer ends of series located more posteriorly than anterior ends; dark ground dorsum, head and tail (slate-black to brown) with numerous, medium-sized (size<SVL/20) yellowish to reddishorange confluent elongated spots and ocelli, ventral side purplish gray; light dorsal band always absent; juveniles with dark ventral trunk, large yellowish blotches on dorsum and tail.

Measurements and counts of holotype:SVL: 54.8; TL:51.8; GA: 26.5; IC: 6.5; CW: 6.3; CGBL: 1; HLL: 15; HL: 12.0 HW: 8.5; EL: 3.4; IN: 5.0; ON: 2.7; IO: 3.2; IC: 6.5; OR: 5.2; 1-FL: 1.6; 2-FL: 2.2; 3-FL: 3.3; 4-FL: 2.0; 1-TL: 1.6; 2-TL: 2.1; 3-TL: 3.1; 4-TL: 3.0; 5-TL: 2.7; VTL: 1.9; VTW: 4.5; MTH: 4.7;MTW: 4.0; MAXTH: 7.1; CGN(L): 11; CGN(R): 11; VTN(L): 21;VTN(R): 22. Please refer to the Supplementary Materials for measurements and counts of type series, morphological measurements of referred specimens, detailed description of holotype coloration and morphology, and variation and natural history of new species.

Etymology:The specific name “sillanus” is a toponymic adjective in the nominative singular, masculine gender,referring to the historical Korean kingdom of Silla (57 BC-935 AC) located on the southeastern parts of the Korean Peninsula, coinciding with the geographic distribution of the new species.

Common names:We suggest “Yangsan Clawed Salamander” as the common name in English and “Yangsan Ggorichire Dorongnyong” (Kkorichire Dorongnyong) (양산꼬리치레도롱뇽) as the common name in Korean, in reference to its distribution.

Comparisons:Within theO. koreanusgroup,Onychodactylus sillanussp. nov.is most closely related toO. zhaoermii,O.koreanus, and undescribed cladeOnychodactylussp. B from Gangwon Province in R. Korea. It forms a monophyletic group with the latter two species and comparisons of the new species withO. zhaoermiiandO. koreanusare the most pertinent. The new species differs fromO. koreanusby modal costal grooves 11 (vs. higher CGN count and modal costal grooves 13 (12-13) for both sexes inO. koreanus); vomerine teeth 18-22 (mean 20) in each series (vs. VTN count 10-18(mean 16.4±2.21) inO. koreanus); inner branch of vomerine tooth arch notably curved forward at medial end (vs. inner branch of vomerine tooth arch not curved at medial end inO.koreanus); light markings on dorsum forming confluent blotches and spots (vs. light markings on dorsum usually not confluent and not forming reticulate pattern inO. koreanus);and front and back limbs in larvae FLL/SVL 0.09-0.13(1.11±0.01 mean±SD) and HLL/SVL 0.10-0.16 (0.12±0.01)(vs. FLL/SVL 0.07-0.12 (0.09±0.01) and HLL/SVL 0.07-0.13(0.11±0.01) inO. koreanus).

Onychodactylus sillanussp. nov.further differs fromO.zhaoermiiby vomerine teeth 18-22 (mean 20) in each series(vs. vomerine teeth usually less than 16 per series (mean 13.8±1.3) inO. zhaoermii); and light markings on dorsum forming confluent blotches and spots, with light ocelli in adults(see Figure 1) (vs. light markings on dorsum forming dense reticulated pattern, with light ocelli absent inO. zhaoermii).Onychodactylussillanussp. nov.differs from other congeners based on a combination of the following morphological attributes: average number of costal grooves 11; slightly bent vomerine tooth series, with higher number of vomerine teeth in each series (mean 20); typical coloration of juveniles and adults (Supplementary Figure S7), dark-brown ground color with numerous small, round and bright golden to orange spots,and no distinct dorsal band.

Current distribution and climate change:Chang et al.(2009) provided the first record of the new species from Unmun Mountain asO. fischeri. Modeling placed the extent of occurrence (EOO) ofOnychodactylussillanussp. nov.at 792.7 km2based on the Maxent binary map and 258.3 km2based on the minimum convex polygon (MCP). This small range is predicted to shrink further as all binary maps from the forecasted ENMs showed a drastic reduction in suitable habitat forOnychodactylussillanussp. nov.(Supplementary Figure S8). The models for 2050 predicted 32.1 km2of suitable habitat under the RCP 4.5 scenario and 21.6 km2of suitable habitat under the RCP 8.5 scenario (Figure 1).Models based on later time frames and higher RCPs predicted even greater decreases in suitable habitat (Supplementary Materials).

Conservation assessment:According to the international Protected Planet database (https://www.protectedplanet.net/),suitable habitat forOnychodactylussillanussp. nov.overlaps with several protected areas of significance. The species is also present or expected to be present in five protected areas in R. Korea (see list in Supplementary Materials). The projected population size reductions based on EOO declines and climate change predictions for 2050 well match the IUCN Red List Category A3(c). The RCP 4.5 scenario resulted in a decline of 87.6% (MCP) and 95.9% (Maxent binary) and the RCP 8.5 scenario resulted in a decline of 91.6% (MCP) and 97.3% (Maxent binary). Under such scenarios, the species would reach the status of Critically Endangered under Category A3(c). Based on EOO, the current geographic range ofOnychodactylussillanussp. nov.was estimated at 792.7 km2(Maxent binary) and 258.3 km2(MCP). Thus, we recommendOnychodactylussillanussp. nov.be classified as Critically Endangered under Category A3(c) of the IUCN Red List. Our findings highlight the need for a coordinated conservation action plan covering all areas where the species is known to occur.

In the current study, based on morphometric, genetic, and ecological niche modeling, we describe a newOnychodactylusspecies (Onychodactylussillanussp. nov) restricted to the southeastern margin of the Korean Peninsula. In addition, we link species description to threat assessments based on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. We suggest the species be listed as Critically Endangered, in view of projections of future areas based on climate change scenarios, or as Endangered, based on the size of the current EOO. Without conservation action, the newly described species is facing an uncertain future.

NOMENCLATURAL ACTS REGISTRATION

The electronic version of this article in portable document format represents a published work according to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN),and hence the new names contained in the electronic version are effectively published under that Code from the electronic edition alone (see Articles 8.5-8.6 of the Code). This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the online registration system for the ICZN. The ZooBank LSIDs (Life Science Identifiers) can be resolved and the associated information can be viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix http://zoobank.org/.

Publication LSID:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:66EEAC0C-2421-43B2-84D2-BF11684EFEE5

Onychodactylus sillanusLSID:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C62AAA19-197A-4B6C-BA6CAD231FDA0874

SCIENTIFIC FIELD SURVEY PERMISSION INFORMATION

All observations and experiments conducted in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical recommendations of the College of Biology and the Environment at Nanjing Forestry University.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A.B. and M.S.M. designed the study. A.B., Y.S., N.A.P., J.Y.J.,H.J.B., C.H.L., J.A., Y.J.H. and M.S.M. conducted field work and data analysis. A.B., Y.S., N.A.P., and M.S.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Tae Ho Kim, Dong Youn Kim, Min Seob Kim, and Il Hoon Kim for assistance in the field. Nikolay A. Poyarkov kindly thanks K. Sarkisian and J.H. Yoon for support and assistance. The authors thank all anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Amaël Borzée1,#,*, Yucheol Shin1,2, Nikolay A. Poyarkov3,Jong Yoon Jeon4, Hae Jun Baek4, Chang Hoon Lee4,Junghwa An5, Yoon Jee Hong5, Mi-Sook Min4,#,*1Laboratory of Animal Behaviour and Conservation,College of

Biology and the Environment,Nanjing Forestry University,Nanjing,Jiangsu210037,China2Department of Biological Sciences,School of Natural Science,

Kangwon National University,Chuncheon24341,Republic of Korea

3Department of Vertebrate Zoology,Biological Faculty,M.V.Lomonosov Moscow State University,Moscow119234,Russia

4Research Institute for Veterinary Science,College of Veterinary Medicine,Seoul National University,Seoul08826,Republic of Korea5Animal Resources Division,National Institute for Biological Resources,Incheon22689,Republic of Korea

#Authors contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding authors, E-mail: amaelborzee@gmail.com;minbio@yahoo.co.kr

- Zoological Research的其它文章

- Diversity of reptile sex chromosome evolution revealed by cytogenetic and linked-read sequencing

- Coevolutionary insights between promoters and transcription factors in the plant and animal kingdoms

- Deficiency of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein γ-8 leads to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder-like behavior in mice

- Global cold-chain related SARS-CoV-2 transmission identified by pandemic-scale phylogenomics

- The Hippo pathway and its correlation with acute kidney injury

- Genomics and morphometrics reveal the adaptive evolution of pikas