Extending Beijing’s Ancient Backbone

By staff reporter YI LI

THE concept of a “center” is one of the most distinctive characteristics of Chinas traditional culture, and is reflected in the design of the countrys ancient cities like Beijing. While the traditional layout of the capital is still evident, in contemporary times the Olympic Games have seen the capitals ancient backbone extended northward.

Ancient Axis

Beijings origins and development are firmly linked to the concept of a north-south central axis. When the Yuan Dynasty built its capital Dadu on the site of contemporary Beijing over 700 years ago, it was constructed around a north-south axis tangential to the east side of Shichahai. The line was extended southward during the Ming Dynasty, and became a 7.8-kilometer-long axis running between the Drum and Bell towers in the north, and Yongding Gate in the south. This axis, which also runs through Zhengyang Gate, the Forbidden City and Coal Hill, still forms the citys backbone today.

According to ancient architectural precepts, the imperial city and palace had to sit in the middle of the citys central axis, while ancestral temples were built to the left, an Altar of Land and Grain to the right, imperial government offices in front of the palace, and a market at the back. Other important buildings were located on either side of the axis, such as Xihuamen (Gate of Western Glory) and Donghuamen (Gate of Eastern Glory).

Following the establishment of the Ming Dynasty in 1368, many altars and temples were built in Beijing, such as the Altar of the Sun in the east, the Altar of the Moon in the west, and the Altar of the Earth in the north. The most famous altar of all is the Temple of Heaven, east of the central axis southern point. This sacrificial altar was visited by the Emperor every winter solstice (the 22nd or 23rd of December) to worship Heaven.

The gate on the axis southern tip, Yongdingmen, was originally built in 1553 to reinforce the capitals defenses. The original structure was demolished in 1957. A reconstructed replica stands on the spot today.

The 500-year-old Zhengyangmen, a gate which once divided the ancient inner and outer cities, still stands at the southern end of Tiananmen Square. It formerly marked the southern periphery of the Forbidden City. The Forbidden City itself was constructed from 1406 to 1420 in the Ming Dynasty, and today represents the largest surviving slice of ancient architecture in China. North of the sprawling imperial complex lies Coal Hill, site of the imperial garden.

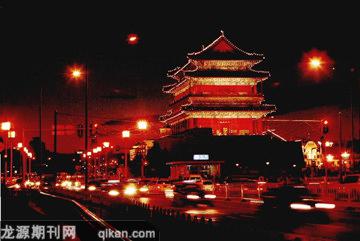

The Bell and Drum Towers, marking the northern end of Beijings ancient central axis, are also thankfully still extant. They tolled every hour during the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties.

On New Years Day 2002, the Bell and Drum Towers opened to the public, and every Spring Festival since the bell and drum have sounded again, ending nearly 100 years of silence.

For the 1990 Asian Games held in Beijing, the Asian Games Village (Yayuncun) was built on a northern extension of Beijings ancient axis, taking the length of the line to 13 kilometers.

Extending the Axis for the Olympics

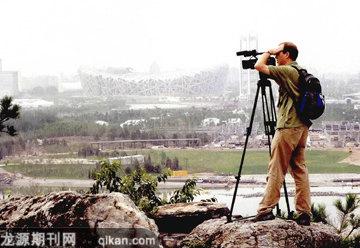

For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the axis has been extended northward once again, and now stretches over 26 kilometers. The Olympic Park now forms the northern end, holding 10 Olympic venues such as the “Birds Nest,” or National Stadium, and the “Water Cube,” or National Aquatics Center. The park is also home to the Olympic Village and the National Indoor Stadium.

A dragon-shaped waterway encircles the park, laid out symmetrically with Shichahai on the axis western side, making for a harmonious integration of culture and landscape.

Unlike the axis ancient sections, the recent extension features no buildings astride the axis itself. Professor Hou Renzhi, an authority on Beijings history and geography, once offered a suggestion about the design of the axis northern end, which made reference to the Forbidden Citys moat and the earth dug up in its construction, which was used to form Coal Hill during the Ming Dynasty. However, when the various designs for the Olympic Park were considered six years ago, authorities could not come to a decision about what to build on the northern tip. “At present, we are still not sure what kind of structure should be placed in the park at the end of the axis,” says world-renowned architect Liu Taige, who was director of the evaluation committee. “Thus we decided to leave this for later generations to settle.”