青藏高原东缘块茎堇菜鳞茎分配的个体大小依赖性

郝 楠, 苏 雪, 吴 琼, 常立博, 张世虎, 孙 坤

( 西北师范大学 生命科学学院, 兰州 730070 )

青藏高原东缘块茎堇菜鳞茎分配的个体大小依赖性

郝楠, 苏雪, 吴琼, 常立博, 张世虎, 孙坤*

( 西北师范大学 生命科学学院, 兰州 730070 )

摘要:块茎堇菜(Viola tuberifera)为青藏高原特有两型闭锁花植物,属多年生草本,具独特的混和交配系统,既可通过早春开放花异花受精和夏季地上地下闭锁花自花受精有性繁殖,还可通过秋季新鳞茎无性繁殖产生后代。高山环境下,异花受精常因花粉限制而无法正常进行,自花受精和克隆繁殖成为保障植物种群正常繁衍的不二之选,而克隆繁殖更能在植株资源消耗最小的情况下保障子代的存活。该文以青藏高原东缘高寒草甸的混合繁育植物块茎堇菜为研究对象,探索其生长期内鳞茎分配的个体大小依赖性,以及植株如何权衡鳞茎的资源分配以适应个体大小的变化。结果表明:块茎堇菜生活史阶段的鳞茎分配具有个体大小依赖性,鳞茎分配与个体大小呈极显著负幂指数相关关系(P<0.01),个体越大,鳞茎分配越小;反之,个体越小,鳞茎分配越高。即块茎堇菜对鳞茎的资源投入受个体大小的制约,通过鳞茎分配比例的高低响应植株自身资源状况的变化,保障在高寒环境下植物种群的生存和繁衍。该研究结果为高山植物克隆繁殖的生活史进化提供了依据。

关键词:繁殖生态学, 生长期, 混合交配, 无性繁殖, 总生物量

大多数多年生植物种存在混合繁殖方式,不仅可以选择有性繁殖策略,还可以通过营养繁殖产生后代(钟章成,1995)。克隆繁殖对植物种群的生活史会产生不同程度的影响。当生物或非生物因子使其中一种繁殖方式受限时,植株繁殖策略的选择在种间和种内均会发生较大变化(Eckert,2001;Eckert et al,2003)。高山环境对混合繁殖构建的克隆居群影响非常明显,自然选择倾向于保障植物的克隆繁殖方式,可能是因为高寒条件下植株通过有性繁殖产生后代比较困难,所以高山植物大多选择营养器官生长繁殖(钟章成,1995)。

对克隆植物种群的繁殖生态学研究已引起植物生态学家和进化植物学家的广泛关注(卜兆君等,2005;Li & Wang,2006)。植物在生活史阶段中对繁殖器官投入的比例称为繁殖分配(reproductive allocation)。有关克隆植物繁殖分配的适应策略研究多集中在有性繁殖和无性繁殖的权衡方面(Pickering,1994;Reekie,1998;王一峰等,2012;赵方和杨永平,2008)。繁殖分配常与植物自身的资源状况紧密相关,个体大小常用来反映较为稳定的环境条件下居群内植物个体资源分配的差异(Samson & Werk,1986)。植物的繁殖分配是个体大小依赖的,但有关工作大多集中在有性分配方面(陶冶和张元明,2014;刘左军等,2002;赵志刚等,2004),有关无性繁殖分配的个体大小依赖性研究在国内鲜有报道。鉴于此,本文以青藏高原东缘两型闭锁花植物块茎堇菜为研究对象,探究其克隆繁殖的个体大小依赖性,以期为克隆植物特殊的生殖模式和对高山环境的生态适应性提供实验依据。

1材料与方法

1.1 研究样地概况

研究样地位于青藏高原东缘甘南藏族自治州合作境内(102°18′~102°55′ E,34°28′~35°11′ N),海拔 2 600~3 500 m,平均气温 1.8 ℃,年降雨量 572 mm。研究区属典型高原大陆性气候,没有四季之分,仅冷暖二季。温差年均较小,日均较大,辐射强烈。土壤为高山草甸土、亚高山草甸土、沼泽土、泥炭土和暗棕壤等。植被类型主要有高寒灌丛、高寒草甸和沼泽化草甸(杜国祯,2001)。

1.2 研究方法

在块茎堇菜的生长季节内6-9月,每个月随机选取3~5 个样方,每个样方挖取完整植株60 株左右,每株间隔>1 m。去除泥土和杂草,所有材料置于信封内带回实验室,80 ℃烘箱内烘2 h至恒重,于万分之一天平对每株个体的总生物量和鳞茎生物分别称重,记录数据。计算鳞茎分配(鳞茎生物量占总生物量的比例)。以总生物量衡量个体大小。

1.3 数据处理与分析

所有数据用Excel 2003和SPSS 21.0软件处理,先进行正态分析,若正态则单因素方差分析数据的显著性差异,若不正态则用独立样本检验比较各组数据间的差异;然后回归分析两组数据间的相关关系,且做图。种群水平下均采用均值 ± 标准误的数值,个体水平下均采用实际测得的数值。

2结果与分析

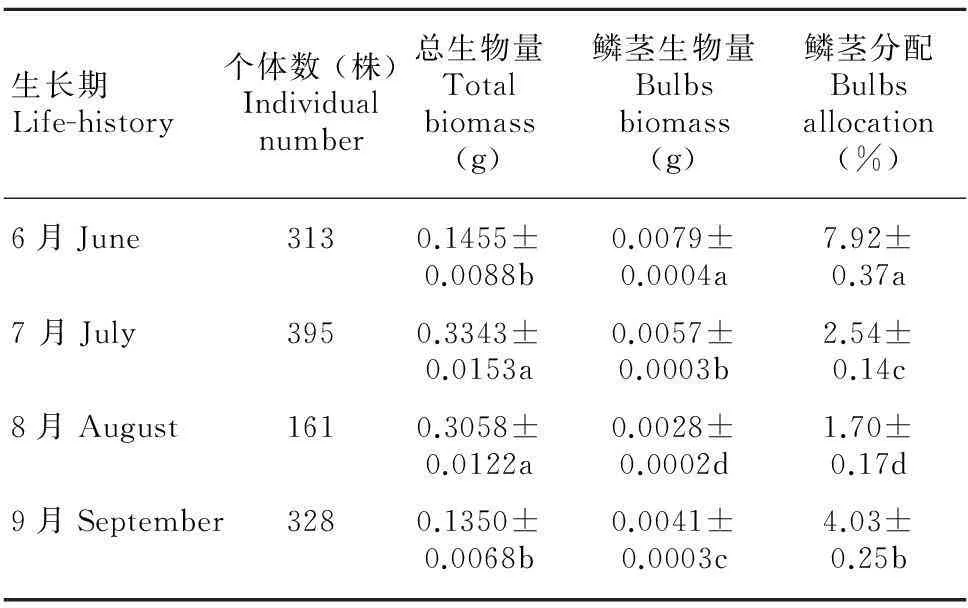

2.1 块茎堇菜的鳞茎分配

表1显示,在块茎堇菜的整个生长期内,总生物量在闭锁花时期(7、8 月)达到最高,约为初末期(6、9 月)的2.5倍,总生物量随季节变化呈先上升后下降的趋势,且季节间差异显著(P<0.05)。鳞茎生物量在8 月份最小,这是由于8 月份是鳞茎枯萎期,鳞茎数目很少;初期(6 月)鳞茎生物量最高,这是因为生长初期大多数植株是由前一年的鳞茎长出来的个体。鳞茎分配在生长初期和末期达到最大,由于末期鳞茎大量产生保障越冬繁殖,所以投入较多;在8 月份,鳞茎分配比例最低。总体看,随着块茎堇菜生长期的推移,鳞茎生物量及分配呈先降低后升高的趋势,且各生长期的变化显著(P<0.05)。

表 1 块茎堇菜生长期的鳞茎分配格局

注:所有值为均值 ± 标准误的形式。数字不同表明在P=0.05水平上差异显著,数字相同表明差异不显著(P<0.05)。

Note: All values are Mean ± SE. Values with different letters show significant differences at 0.05 level, while with same letters show non-significant differences(P<0.05).

2.2 块茎堇菜鳞茎分配的个体大小依赖性

图1显示,在生长初期(6月),块茎堇菜刚刚返青,植株个体较小,野外观察发现,大多植株由鳞茎长出来,通过个体大小与鳞茎分配的相关关系分析发现,个体大小与鳞茎分配呈极显著负幂指数相关关系(P=0.000),相关性较大(r=-0.765)。在闭锁花生长初期(7月),地上和地下闭锁花逐渐出现,植株个体慢慢变大。块茎堇菜的个体大小与鳞茎分配的相关分析表明,个体大小与鳞茎分配呈极显著负幂指数相关关系(P=0.000),相关性大(r=-0.803)。在闭锁花盛花期(8月),地上和地下闭锁花达到最多,植株个体较大。通过对块茎堇菜的个体大小与鳞茎分配的相关分析表明,个体大小与鳞茎分配呈极显著负幂指数相关关系(P=0.000),相关性大(r=-0.818)。在生长季节末期(9月),鳞茎大量产生,植株个体逐渐变小。块茎堇菜的个体大小与鳞茎分配呈极显著负幂指数相关关系(P=0.000),相关性较大(r=-0.614)。即在块茎堇菜的整个生长阶段内,鳞茎分配具有大小依赖性。

3讨论与结论

高山环境下,克隆植物具有独特的繁殖策略——有性和无性繁殖。不同繁殖对策的选择权衡受内外因素的影响。Salisbury(1942)通过研究177种多年生草本,发现其中120 种(占68%)植物克隆繁殖。因为在很多情况下,克隆繁殖比有性繁殖更加容易,其克隆后代对环境有更大的适应性。克隆后代可以在激烈的竞争和严酷的环境下,通过无性繁殖在非最适宜的条件下延续后代,提高子代的生存能力。与有性繁殖相比,克隆繁殖的子代缺少遗传变异性,但其子代存活率要远高于种子幼苗建成的概率,如葡伏毛茛种子形成幼苗的寿命为0.2~0.6 a,而无性分株(module)的寿命却为1.2~2.1 a(Sarukhan & Harper,1973)。

Schmid et al(1995)通过比较细叶紫菀(Asterlanceolatus)和加拿大一枝黄花(Solidagocanadensis)的有性和无性繁殖的个体大小依赖性,结果表明两种植物都在个体达到最小临界值时才可以开始有性繁殖,有性繁殖分配随个体增加而增加;两种植物对无性繁殖的分配与个体存在相关关系,但无性繁殖不存在最小个体临界值。Sato(2002)对多年生草本植物珠芽艾麻(Laporteabulbifera)的研究得出了类似结论,研究发现较大的个体能同时产生雌雄花序和无性繁殖器官, 而较小的个体只产生无性繁殖器官,有性和无性繁殖器官的生物量均与个体大小呈正相关关系。这与Dong & De Kroon(1994)、Schmid et al(1995)的研究有所不同,他们认为克隆植物对无性繁殖的分配在较大的个体内常常是恒定的。

图 1 块茎堇菜生长期个体大小与鳞茎分配的关系Fig. 1 Relationship between individual size and bulbs allocation in life-history V. tuberifera

块茎堇菜的无性繁殖在整个生长季节内呈规律性变化。在生长季节初末期,鳞茎生物量和分配均较高,在闭锁花时期鳞茎生物量及分配较低,且在闭锁花盛花期(8 月)达到最低。这与其鳞茎的生物学特性紧密相关,在生长季节初期,上一年的鳞茎萌发产生新个体,鳞茎生物量所占比例相对较大,随个体发育到闭锁花时期,植株大量产生两种闭锁花进行有性繁殖,而老的鳞茎大多已枯萎,因此该阶段鳞茎生物量及其分配均较低;但在生长季末期,块茎堇菜大量产生鳞茎以保障越冬和来年的繁殖。通过分析发现,块茎堇菜的克隆繁殖分配具有个体大小依赖性,即个体越大,鳞茎分配越小。但是鳞茎分配也存在临界值,在个体大小到达一定值后,鳞茎分配值不再随着个体大小的增加而下降。这可能是由于较大的个体同时将资源投入到有性繁殖器官、无性繁殖器官和营养生长保障植物的繁殖和生存,相比较之下,对无性繁殖的投入和分配较小;而较小的个体由于自身资源获取能力较弱,将有限的资源主要用于营养器官的生长和繁殖,旨在通过鳞茎的营养生长保障繁殖,延续后代。

参考文献:

BA ZZA FA, ACKELY DD, 1992. Reproductive allocation and reproductive effort in plants [J]. Ecol Reg Plant Comm.

BU ZJ,YANG YF,LANG HQ,et al. 2005. Regeneration mechanism of the clonalCarexmiddendorffiipopulation in an oligotrophic mire, China [J]. Acta Pratac Sin, 14:124-129. [卜兆君,杨允菲,朗惠卿,等. 2005. 贫营养泥炭沼泽高鞘苔草无性系种群更新机制 [J]. 草业学报, 14:124-129.]

DONG M, DE KROON H, 1994. Plasticities in morphology and biomass allocation inCynodondactylon,a grass species forming stolons and rhizomes[J]. Oikos,70:90-106.

DU GJ, 2001.Research of plant ecology in alpine meadow [M]. Xi’an:Shaanxi Sicence and Technology Press. [杜国祯, 2001. 高寒草甸植物生态学研究 [M]. 西安:陕西科学技术出版社.]

ECKERT CG, 2002. The loss of sex in clonal plants [J]. Evol Ecol,15:501-520.

ECKERT CG, LUI K, BRONSON K, et al, 2003. Population genetic consequences of extreme variation in sexual and clonal reproduction in an aquatic plant [J]. Molecu Ecol,12:331-344.

LI L, WANG G, 2006. The ideal free distribution of clonal plant’s ramets among patches in a heterogeneous environment [J]. Bull Mathem Biol,68:1 837-1 850.

LIU ZJ,DU GJ, CHEN JK, 2002. Size-dependent reproductive allocation ofLigulariavirgaureain different habitats [J]. Acta Phytoecol Sin,26(1):44-50. [刘左军,杜国桢,陈家宽, 2002. 不同生境下黄帚橐吾(Ligulariavirgaurea)个体大小依赖的繁殖分配 [J]. 植物生态学报,26(1):44-50.]

PICKERING CM, 1994. Size-denpendent reproduction in Australian alpineRanunculus[J]. Aus J Bot,76:43-50.

REEKIE EG, 1998. An explanation for size-dependent reproductive allocation inPlantagomajor[J]. Can J Bot,76:43-50.

SALISBURY EJ, 1942. The reproductive capacity of plant, Bell London(A classic text wite early quantitative, data on seed sizes and numbers per plant).

SAMSON DA, WERK KS, 1986. Size-dependent effects in the analysis of reproductive effort in plants [J]. Am Natur, 127:667-680.

SARUKHAN J, HARPER JL, 1973. Studies on plant demography:RanunculusrepensL.,R.bulbosusL. andR.acrisL.Ⅰ. population flux and survivorship [J]. J Ecol, 61:675-716.

SARUKHAN J, 1974. Studies on plant demography:RanunculusrepensL.,R.bulbosusL. andR.acrisL.Ⅱ. reproductive strategies and seed population dynamics [J]. J Ecol, 62:151-177.

SATO T, 2002. Size-dependent resource allocation among vegetative propagules and male female functions in the forest herbLaporteabulbifera[J]. Oikos, 96,453-462.

SCHIMID B, BAZZAZ FA, WEUBER J, 1995. Size-dependency of sexual reproduction and of clonal growth in two perennial plants [J]. Can J Bot, 73:1 831-1 837.

TAO Y,ZHANG YM, 2014. Biomass allocation patterns and allometric relationships of six ephemeroid species in Junggar Basin, China [J]. Acta Pratac Sin, 23(2):38-48. [陶冶,张元明, 2014. 准格尔荒漠6种类短命植物生物量分配与异速生长关系 [J]. 草业学报, 23(2):38-48.]WANG YF, LI M,LI SX, ET AL, 2012. Variation of reproductive allocation along elevations inSaussureastellaon East Qinghai-Xizang Plateau [J]. J Plant Ecol, 36(11):1 145-1 153. [王一峰,李梅,李世雄等, 2012. 青藏高原东缘星状风毛菊生殖分配对海拔的响应[J]. 植物生态学报, 36(11):1 145-1 153.]

ZHAO F, YANG YP, 2008. Reproductive allocation in a dioecious perennialOxyriasinensis(Polygonaceae) along altitudinal gradients [J]. J Syst & Evol, 46(6):830-835. [赵方,杨永平, 2008. 中华山蓼不同海拔居群的繁殖分配研究 [J]. 植物分类学报, 46(6):830-835.]

ZHAO ZG, DU GZ, REN QJ, 2004. Size-dependent reproduction and sex allocation in five species of Ranunculaceae [J]. Acta Phytoecol Sin, 28(1):9-16. [赵志刚,杜国桢,任青吉, 2004. 5种毛茛科植物个体大小依赖的繁殖分配和性分配 [J]. 植物生态学报, 28(1):9-16.]

ZHONG ZC, 1995. Reproductive strategy of plant population [J]. J Ecol,14(1):37-42. [钟章成, 1995. 植物种群的繁殖对策[J]. 生态学杂志,14(1):37-42.]

Size-dependent of Qinghai-Tibetan PlateauViolatuberifera(Violaceae)bulbs allocation

HAO Nan, SU Xue, WU Qiong, CHANG Li-Bo, ZHANG Shi-Hu, SUN Kun*

(CollegeofLifeSciences,NorthwestNormalUniversity, Lanzhou 730070, China )

Abstract:Viola tuberifera is a typical dimorphic cleistogamous plant which endemic to Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and its eastern neighbour region, belongs to perennial herb, possessing mixed-mating reproductive system, which conducts not only sexual propagation via both open, aerial chasmogamous (CH) flowers in spring and closed, obligate self-pollinating aerial and subterranean cleistogamous (CL) flowers in summer, but also asexual reproduction via new bulbs in autumn reproducing offsprings through winter. Chasmogamous flowers depend on pollinator, such as bumblebees, obligate cross-fertilization producting bigger and few seeds. Cleistogamous flowers do not need pollinators, they can pollinate by themselves and produce smaller and abundant seeds. Further to say, survival ratio of chasmogamous flowers seedings is lower than the cleistogamous flowers offprings. In particular, while plant under harsh environment, cleistogamy can provide reproductive assurance and cost economically. Three flowers are all sexual propagation. Only vegetative organ-bulbs via asexual propagation. Bulbs prapagation can also assure reproduction under adverse habitat. Especially in alpine ecosystem, plants always face to pollination limatation, at this time vegetative propagation can produce offsprings which are similar to stock plant and form ramets to fight for habitats and resources. Parents and offsprings together resist stern climate and through cold environment. That is to say, bulbs reproduction can ensure V. tuberifera surivial and continuation in the high alpine environment and cost mininum resources to through winter. Sexual reproduction is conducted before asexual reproduction and two opposite reproductive strategies can ensure survival together in the whole life history. In the alpine district, allogamy always face pollen limitation and cannot assure plants reproduction, whereas autogamy and clonal reproduction are alternative choices to ensure propagation of plants populations, as well as clonal reproduction can furtherly assure offsprings’ survival with the lowest resources assumption. In this paper, mixed-mating plant-V. tuberifera in eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau alpine meadow were chosen as study material, probing into size-dependent on bulbs allocation during life-history, aiming at how V. tuberifera could trade off resource allocation on bulbs to adapt to changes of individual size, providing evidence for life-history evolution of clonal reproduction in alpine plants. The results showed that bulbs allocation of V. tuberifera endemic to eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau existed size-dependent in the whole life history, bulbs allocation and individual size showed extremely significantly negative exponent correlationship (P<0.01). The bigger the individual size was, the lower the bulbs allocation was, and vice versa. Although individual size was small, plants allocate amounts of resources to asexual organ—bulbs, assuring propagation in winter and survive themselves. When the bulbs allocation came to the maximum, though individual size became bigger, proportion of bulbs did not change any more. Therefore, that individual size controlled resource allocation was within a definite range. Beyond the certain range, individual size no longer affected bulbs allocation. That is to say, resource allocation on bulbs in V. tuberifera is controlled by individual size in a certain range, plants via altering proportion of bulbs allocation to adapting to inner resource condition changes of V. tuberifera, ensuring plants population survival and offsprings propagation in the alpine environments.

Key words:reproductive ecology, life-history, mixed-mating, asexual reproduction, total biomass

DOI:10.11931/guihaia.gxzw201501037

收稿日期:2015-01-28修回日期:2015-05-04

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31260054)[Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31260054)]。

作者简介:郝楠(1991-),女,陕西商洛人,硕士研究生,主要从事植物生态学研究,(E-mail)haonan1022@126.com。 *通讯作者:孙坤,博士,教授,主要从事植物系统进化和生物多样性等研究,(E-mail)kunsun@nwnu.edu.cn。

中图分类号:Q948

文献标识码:A

文章编号:1000-3142(2016)06-0674-05

郝楠,苏雪,吴琼,等. 青藏高原东缘块茎堇菜鳞茎分配的个体大小依赖性[J]. 广西植物, 2016, 36(6):674-678

HAO N,SU X,WU Q,et al. Size-dependent of Qinghai-Tibetan PlateauViolatuberifera(Violaceae)bulbs allocation [J]. Guihaia, 2016, 36(6):674-678