大气中持久性有机污染物的采样技术进展

朱青青,刘国瑞,张宪,董姝君,高丽荣,郑明辉,

1. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心 环境化学与生态毒理学国家重点实验室,北京 100085 2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

大气中持久性有机污染物的采样技术进展

朱青青1,2,刘国瑞1,2,张宪1,2,董姝君1,2,高丽荣1,2,郑明辉1,2,

1. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心 环境化学与生态毒理学国家重点实验室,北京 100085 2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

大气是全球持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants, POPs)监测的重要环境介质,大气中POPs的采样技术是准确表征大气中POPs赋存水平的关键所在。近年来大气中POPs的采样技术发展很快。本文介绍了大气中POPs的两类采样方法:主动采样法(active air sampling, AAS)和被动采样法(passive air sampling, PAS),总结了新型吸附材料和新型采样器研发的成果,讨论了不同类型的采样方法的特点,对比分析了不同采样方法获得的POPs监测数据,并提出今后应用不同POPs大气采样技术在监测数据可对比性研究方面值得关注的问题。

持久性有机污染物;大气;主动采样;被动采样

持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants,POPs)是指在环境中难降解、可以在食物链中富集,能够通过蒸发-冷凝、经大气的远距离传输从而影响到区域和全球环境的半挥发性且毒性很高的污染物。研究表明,POPs污染的严重性和复杂性远远超过常规环境污染物,很多POPs不仅具有致癌、致畸和致突变性,而且还具有内分泌干扰效应,对动物甚至人类的生存和繁衍构成潜在风险。因此,环境中POPs的监测受到了广泛的关注。

大气作为“汇”,汇集土壤、水体及各类大气排放源中的POPs,作为“源”,通过远距离传输和大气沉降向其他介质传输POPs,因此大气是POPs传输的重要媒介。此外,《关于持久性有机污染物(POPs)的斯德哥尔摩公约》第16条规定了为开展履约成效评估而实施全球POPs监测的要求,缔约方大会通过了全球POPs监测行动计划,将空气列为POPs环境监测的核心介质。鉴于大气中POPs对自然环境和人类健康的潜在风险,准确评估大气中POPs的赋存水平是必不可少的,而对于大气中POPs的采集方法的技术研究就显得尤为重要。

为了监测大气中POPs的浓度和评估空气质量,目前通常利用主动大气采样(active air sampling, AAS)或被动大气采样(passive air sampling, PAS)两种方法来采集大气样品。张干和刘向等[1]曾对大气PAS技术的基本原理和几种主要的大气PAS装置进行了较为全面的综述。PAS技术采样装置结构简单、操作方便、造价低廉、无需电力和特别维护,测定结果为时间加权浓度,评价POPs的人体长期暴露水平更具有科学性,具有一定的优势[2-6],且更适合于大范围内POPs的监测[7-11]。Bogdal等[12]报道了利用被动采样技术监测全球五大洲空气中的POPs,也有相关文献已报道应用被动采样监测地球南北极大气中POPs的长距离迁移变化[13]。被动采样器在应用过程中还是存在一些不足:(1)被动采样器对于流量缺乏准确度量,不能精确测定大气中POPs浓度。(2)POPs在采集过程中因周期较长可能发生解吸,影响分析结果。(3)被动采样器无法表征污染物在短时间内的浓度变化[14]。传统的大气POPs采样方法是AAS,该技术能够精确测定流量,并计算出每次采集的大气体积,提高数据的准确程度;其流量较大,采样时间短,可在几天时间内获得数百立方米乃至数千立方米的大气样品,避免因采样时间过长POPs发生解吸的问题;同时还可以捕捉到污染物在短时间内的浓度变化。但是,AAS依赖电力支持,在缺乏电力供应的偏远地区将无法实施采样活动,此外,由于装置的限制,无法实现大区域大尺度上大气POPs的多点位同时采样分析。综上,PAS和AAS两种大气POPs采样手段相互补充可以满足大气中POPs监测的需求。

1 大气中POPs采样方法(Atmospheric POPs sampling techniques)

1.1 主动大气采样

目前普遍采用的主动采样主要有总悬浮颗粒物(total suspended particles, TSP)采样、粒径小于10 μm的颗粒物(PM10)采样和不同粒径大气颗粒物采样。关于大气中POPs的主动采样方法主要参考如下几种标准方法:美国环保局针对二恶英类(polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans, PCDD/Fs)、溴代二恶英类(polybrominated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans, PBDD/Fs)和多氯联苯(polychlorinated biphenyls, PCBs)提出的TO-9A方法、针对有机氯农药(organochlorine pesticides, OCPs)的提出TO-4A方法和斯德哥尔摩公约通过的《全球POPs监测技术导则》中建议的大流量PM10采样方法。

1.1.1 TSP采样

多数国家采用美国环保局提出的TO-9A方法开展POPs监测[15-16],即采集TSP和吸附气相中POPs合并计总量的方法。该采样法是利用采气泵,形成负压使大气通过采样器的捕集装置,再利用安装在捕集装置内的吸附材料对POPs的吸附、吸收等作用而进行采样的方法,如聚氨酯软性泡沫(polyurethane foam, PUF)、半透膜(semi-permeable membrane, SPM)、玻璃纤维滤膜(glass fiber filter, GFF)和石英纤维滤膜(quartz fiber filter, QFF)等吸附材料。该采样方法可由内置流量计获得精确的采样气体体积,通常采用的主动采样器有大流量主动采样器和小流量主动采样器。采用的采样器通常配备的吸附材料是QFF和PUF吸附剂。TO-9A方法中要求每24 小时的采样体积需达到325~400 m3,采样速率0.114~0.285 m3·min-1。

1.1.2 PM10采样

为了能更好地表征POPs的远距离迁移特性,2007年斯德哥尔摩公约秘书处组织编写并获得缔约方大会通过的《全球POPs监测技术导则》要求采用具有切割器的采样头,采样头只采集粒径小于10 μm的颗粒物,采集的PM10和吸附气相中POPs合并计总量,采样器如图1(a)[14]所示。这种采样方法在极地和一些长期环境背景监测站已有比较成功的应用案例,但相对于大流量TSP采样法的应用仍相对较少。

1.1.3 不同粒径大气颗粒物采样

主动采样中除常规的大流量TSP采样和PM10采样外,还针对不同粒径大气颗粒物设计了相关的主动采样器。如Ma等[17]利用安德森颗粒物采样器(GUV-15HBL1)采集大气中粒径小于2.5 μm的颗粒物(PM2.5),研究其中多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs)的浓度水平和分布。Chrysikou等[18-19]利用安德森大流量颗粒物分级采样器采集了5个不同粒径范围的颗粒物,颗粒物的动力学直径(dae)分别为:<0.95 μm,0.95~1.5 μm,1.5~3 μm,3~7.5 μm和>7.5 μm,研究发现OCPs和PCBs在冬季和夏季均主要存在于dae<0.95 μm的颗粒物中。Kaupp等[20]利用大气颗粒物分级采样器采集德国巴伐利亚东北部的5个不同粒径范围的颗粒物(<0.32 μm,0.32~0.95 μm,0.95~2.9 μm,2.9~8.6 μm和8.6~26 μm),发现约92%的高氯代二恶英(Cl7-8DD/Fs)存在于dae<2.9 μm的颗粒物中,并且随着粒径的增大,颗粒物中的含量逐渐降低,当dae>8.6 μm,平均仅为3.4%。Oh等[21]研究6个不同粒径范围的大气颗粒物(<0.41 μm,0.41~0.73 μm,0.73~1.4 μm,1.4~2.1 μm,2.1~4.2 μm,4.2~10.2 μm和>10.2 μm),发现在dae<0.41 μm的颗粒物中,PCDD/Fs的含量达到60%以上;在dae<2.1 μm的颗粒物中,PCDD/Fs的含量达到90%。Chao等[22]发现大于80%的PCDD/Fs存在于dae<2.0 μm的细颗粒物中。Zhang等[23]研究北京近郊大气中PCDD/Fs和PBDD/Fs在不同粒径颗粒物中的分布,发现PCDD/Fs和PBDD/Fs均主要存在dae<1.0 μm的颗粒物中。此外,微孔碰撞多级采样器(micro-orifice uniform deposition impactor, MOUDI)和Nano-MOUDI等小流量主动采样技术常用于采集不同粒径的大气颗粒物,MOUDI的采样级数可以达到10级,采样粒径范围为0.056~18 μm,Nano-MOUDI的采样级数可以达到13级,采样粒径范围为0.01~18 μm。目前这2种采样技术主要用来分析大气中水溶性离子、微量元素和一些有机成分,如有机碳、PAHs等[24-25]。Chuang等[26]利用MOUDI采集一家轮胎制造厂空气中的PCDD/Fs,发现PCDD/Fs在粒径<1.0 μm颗粒物中的总毒性当量分别是>18 μm和2.5~10 μm的2.2和3.2倍。传统的主动采样器一般是固定式的,为解决其相对不灵活这一缺点,Zhang等[27]开发了一种新型的移动式的主动采样法,即配备一个汽车空气过滤器,可用来分析城市空气中PCDD/Fs的浓度水平。

1.1.4 影响主动采样的因素

影响主动采样的因素主要有采样头的选择、吸附材料和滤膜的选择、采样是否穿透、样品在滤膜上的挥发和吸附损失以及采样过程中的降解影响等[28]。Melymuk等[28]对该部分内容作了较为全面的综述,下面着重介绍吸附材料和气象条件的影响。

1.1.4.1 吸附材料的选择

大气中的POPs一般以颗粒相和气相的形式存在。大气颗粒相中POPs的吸附材料可选GFF、QFF等材料。气相中POPs采集所用的吸附剂则有所不同,可选用的吸附剂包括PUF塞、XAD树脂、双PUF塞、Tenax TA、聚二甲基硅氧烷、PUF与XAD树脂混合体和PUF-活性炭纤维膜(active carbon fiber felt, ACF)-PUF等。不同吸附材料的填充方式有所不同。

目前最常用的气相吸附剂是PUF塞。张颖等[14]使用PUF和GFF作为吸附材料,在中国8个区域11个采样点,检测了全国范围内大气中12种POPs的污染水平。Mari等[29]根据TO-9A方法,使用PUF塞作为吸附材料,在西班牙的巴塞罗那采集了4个采样点的大气样品,测定了其中的PCDD/Fs、PCBs和多氯萘(polychlorinated naphthalenes, PCNs)的浓度。为防止挥发性较大的化合物在PUF塞中发生穿透,Alegria等[30]使用双PUF塞采集并分析了墨西哥南部大气中的OCPs和PCBs的浓度水平。Xiao等[31]和刘碧莲等[32]也有相关报道,采用双PUF塞采集大气中的POPs。总的来说,PUF塞的应用较为简单、经济和广泛,但是PUF塞在使用中仍存在一定的不足:(1)不能吸附低分子量或挥发性较大的化合物,需要使用其他系列PUF塞进行校正;(2)PUF塞的预处理需要花费时间较长;(3)前处理和萃取时需要耗费大量溶剂[33]。为改进这些缺点,Elisabeth等[33]提出使用吸附剂浸渍的滤膜(sorbent-impregnated filters, SIFs),其选用浸渍XAD-4树脂的玻璃纤维滤膜(XAD-SIFs)作为吸附材料,分析测定了大气中的半挥发有机物和PAHs,并发现filter-SIF-SIF-PUF(F-S-S-P)对半挥发性有机物的采集效率优于传统的filter-PUF(F-P),单个SIF的采集效率约为80%。XAD是一种苯乙烯-二乙烯基共聚物,与PUF塞相比具有较大的保留容量。且XAD-SIFs还具有以下特点:可以减小体积,方便样品的装卸、运输和储存,节约前处理的溶剂使用量。此外,还有研究者提出一些新型的吸附剂来采集大气样品,如Jin等[34]使用类似三明治的PUF-ACF-PUF作为气相吸附材料,采集并测定韩国典型背景点大气中的OCPs。Yagoh等[35]使用活性炭纤维滤纸(activated carbon fiber filter paper, ACFP)和QFF作为颗粒相吸附材料,采集并测定了日本新泻地区大气中PAHs的组成及含量。

图1 大气采样器:(a)主动采样器[14];(b)PUF被动采样器[1];(c)XAD被动采样器[43]Fig. 1 Air samplers. (a) active air sampler[14]; (b) PUF-disk sampler[1]; (c) XAD-based sampler[43]

1.1.4.2 气象条件的影响

不同吸附材料的吸附容量和保留能力不同,将直接影响到主动采样器对大气中POPs的采集效率。而外界的环境变化也是不可忽略的影响因素,不同学者的相关研究结果存在明显差异。Hippelein等[36]发现在德国乡村冬季大气中PCDD/Fs浓度明显高于夏季,研究认为该分布可能与居民冬季燃煤取暖有关。Wallenhor等[37]在研究城市地区大气中PCDD/Fs的分布特征时,也得到相似的结论。Umlauf等[38]在波兰南部的小波兰地区和Cheng等[39]在台湾新竹的研究均有类似结论。然而,Coleman等[40]通过对英国城市大气的测定结果并未发现冬季和夏季PCDD/Fs含量有明显差异,Vilavert等[41]对西班牙塔拉戈纳大气中PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PCNs的浓度进行研究,发现没有明显的季节性变化。以上结果说明PCDD/Fs浓度与温度之间并非存在着固定的规律。此外,湿度、压力和风向风速等气象条件也是大气采样的重要影响因素。Qin等[42]监测中国大连市大气中的PCDD/Fs,发现温度和压力是影响大气中PCDD/Fs浓度的重要影响因素,而湿度和风速则无相关性。Cindoruk等[16]发现大气中PCBs的浓度与温度、风速等气象因素具有相关性,尤其是在沿海地区和半农村地区。因此,在探讨气象因素对大气中POPs浓度的影响时,需结合POPs排放源等因素综合考虑。

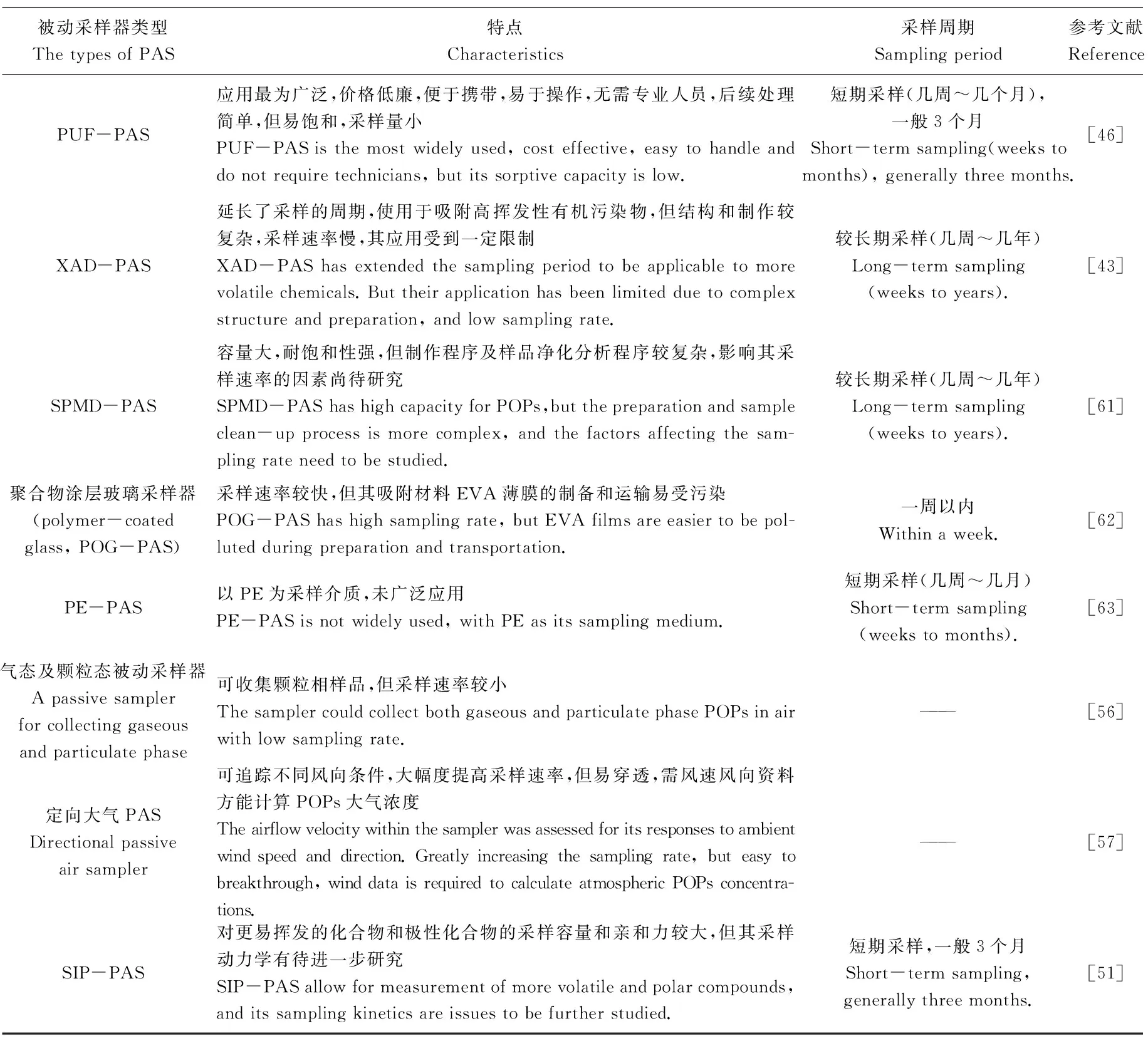

1.2 被动大气采样

PAS是一种既简单又经济的大气采样技术。PAS是基于被分析物的化学势在原本环境和采样介质间的差异进行的一种采样技术[44]。植物作为大气POPs的被动采样介质已被广泛应用于大气监测,赵玉丽等对地衣、苔藓、树叶、树皮等被动采样器在大气POPs监测中的应用作了较为全面的介绍,指出植物被动采样技术在大气POPs历史污染监测中发挥的重要作用[45]。目前,根据不同的吸附剂设计了相应的被动采样装置,如半渗透膜(semi-permeable membrane devices, SPMD)、PUF、XAD、乙烯-醋酸乙烯酯(ethylene vinyl acetate, EVA)和聚乙烯薄膜(PE)等被动采样器。不同被动采样器的特点如表1所示。

PUF-PAS因其具有原理可靠,制作安装简易,材料、运输成本低廉等优点而得到较广泛应用,如图1(b)[1]。Shoeib等[46]将SPMD、PUF和富含有机物的土壤3种吸附材料作为被动采样介质采集大气样品,通过比较发现PUF采样效果最佳。Li等[47]利用PUF-PAS方法采集了中国东北城市鞍山一个大型钢铁工业园区的大气样品,并对其中的PCDD/Fs、PCBs和多溴联苯醚(polybrominated diphenyl ethers, PBDEs)的浓度和来源进行了分析和研究。Moussaoui等[48]也利用PUF-PAS采集了阿尔及利亚北部农村、城市及工业区的大气样品,并分析了PCDD/Fs、类二恶英PCBs(dioxin-like PCBs, dl-PCBs)及一些农药的污染水平。为扩大PUF塞的吸附容量,Harner等[7, 49-50]采用浸渍XAD-4来改进PUF塞(sorbent impregnated polyurethane, SIP)作为吸附材料采集大气中的含氟化合物,并将此方法应用到全球范围的监测计划中。对于容量相对较低的PUF塞,更易挥发的POPs(如六氯苯)在采样期间容易发生饱和,尤其是在温度较高的地方。因此对于采样周期较长的监测项目,可采用XAD采样器,如图1(c)[43],其采样周期可长达1年,且已成功应用于长时间、大尺度的POPs监测[51]。另外还有文献报道使用SPMD采样器进行被动采样,该采样器最开始被用于采集水样,后来因其环境影响小、成本低等特点也慢慢被用于研究大空间范围内大气中的POPs[52-53]。除改进吸附材料外,研究者还开发新型的采样装置,如Fatma Esen采用自行设计的PUF被动大气采样装置采集土耳其布尔萨的大气样品。此装置与其他文献报道的不同之处在于其形状和通风方法,最大限度地降低了风、降雨等环境因素的干扰,如图2(a)[54]。另外,为准确计算被动采样器的大气流量,Xiao等[31, 55]研发了一种新型的利用风向采样的PUF被动采样器(flow-through sampler, FTS),如图2(b),利用风向仪原理,设计了可随风向实时旋转的采样装置。该采样器充分利用风速来提高采样速率,使风吹过采样介质来达到显著加快吸收能力和提供定量信息的目的,其采样速率能达到接近于传统大流量采样器的水平。为解决PAS无法分别采集气相和颗粒相样品这一缺点,Tao等[56]研发了同时采集气态及颗粒态被动采样器。此外,该课题组还设计了定向大气PAS,可以采集某个风向上的大气POPs[57]。

图2 新型PUF被动采样器[54-55]Fig. 2 New types of PUF passive samplers [54-55]

表1 POPs的大气被动采样方法比较

相对于主动采样器,被动采样器无法精确测定流量。因此,为精确采样体积,相关的校正方法被提出。目前普遍采用大流量采样器校正的方法或直接用每个采样器吸附污染物的质量进行比较。如对PUF塞采样器,可用现场研究和流量模拟模型来校正[58-59]。还可采用在PUF上加标的方法,标准物质通常是环境中存在量极少的化合物,如γ-HCH-d6、PCB-107和PCB-198[58, 60]。

2 不同采样方法应用于大气POPs监测的比较(Comparison of monitoring data by using different sampling techniques)

《关于持久性有机污染物(POPs)的斯德哥尔摩公约》第16条规定了为开展履约成效评估而实施全球POPs监测的要求。现有监测结果表明,不同国家采用的大气中POPs监测方法在采样和监测技术等方面还存在差异,监测数据的可比对性在一定程度上影响了履约成效评估。

2.1 主动采样之间的比较

由于环境因素等条件的差异,选择不同的采样头(TSP或PM10)可能导致不一样的采样结果。目前有关不同主动采样法对大气中POPs监测数据的可比性研究相对较少,Martinez等[64]报道了在西班牙8个采样点的大气中TSP和PM10的监测结果具有可比性。然而,全球范围内各采样点POPs的来源及空气质量差异极大,需要有更多实地验证其可比对性或提出可比对的校正系数。杨复沫等[65]报道1999~2000年北京市PM10占TSP的比例平均值为53%,而在地中海沿岸国家,大气颗粒物主要是粒径小于10 μm的颗粒物,PM10/TSP的比值为0.9[66]。Ren等报道了2009年唐山市大气中TSP和PM10的监测结果也具可比性,PCDD/Fs同系物在TSP和PM10中的分布类似,∑CPM10/∑CTSP平均值为0.9,说明PCDD/Fs倾向于存在于PM10以下颗粒物中。Aristizábal等[68]监测了哥伦比亚西部城市马尼萨莱斯的大气中的PCDD/Fs,发现该城市大气中的PCDDs与PM10没有显著相关性。到目前为止,仅有少数关于TSP和PM10监测数据比较研究的报道,并且这些比较大都局限在二恶英类的监测数据比对上[25],对其他POPs的比较研究鲜有报道。因此对大气中POPs的监测方法尚需要更深入的比对研究才能科学评估监测数据的一致性。

2.2 被动采样之间的比较

被动采样作为主动采样的重要补充手段,已受到广泛地关注和应用。Shoeib等[46]比较了SPMD、PUF和富含有机物的土壤3种被动采样介质,发现PUF-PAS对大气中POPs的采样效果最佳。Hayward等[69]利用PUF-PAS和XAD-PAS采集了安大略湖南部农村的大气样品,并分析了其中9种农药的含量,发现两者结果具有一致性。Harner等[7]对PUF-PAS和SIP-PAS进行了比较,发现两者对PCBs采集效率的结果是类似的,但是SIP-PAS对更易挥发的化合物的采集效果明显优于PUF-PAS。

2.3 主动采样与被动采样的比较

目前,主动采样被广泛应用于POPs监测活动,但由于存在需要电力提供等问题,不利于在较偏远地区实施采样活动,而被动采样能够很好地弥补这一缺点而得到迅速发展。但对于被动采样能否作为主动采样的重要补充手段,其关键点在于主动采样和被动采样的数据是否具有可比性。

据大多数相关文献报道证实,主动和被动采样的结果具有可比性。如Gouin等[70]利用大流量AAS和PUF-PAS采集美国劳伦森大湖的大气,测定OCPs、PCBs和PBDEs,发现2种方法所得的数据具有较好的一致性。Levy等[71]利用SPMD、云杉针被动采样和小流量AAS采集了中欧一个森林中的大气样品,发现主动采样和被动采样所得PCDD/Fs的同系物分布相似。Mari等[29]利用大流量AAS和PUF-PAS在西班牙的巴塞罗纳采集了4个采样点的大气样品,测定了PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PCNs的浓度,发现被动采样测得的浓度水平与主动采样相当。Alegria等[30]使用大流量AAS和PUF-PAS采集2002~2004年墨西哥的大气样品,发现2种采样方法中OCPs的浓度水平相当。Hayward等利用4种不同类型的采样方法采集安大略湖南部农村的大气样品,分别为2种AAS(大流量和小流量泵),2种PAS(PUF和XAD树脂)。分析其中9种农药的含量,发现上述不同采样方法的结果具有一致性[69]。He等[72]利用大流量AAS和PUF-PAS采集大气样品,通过单因素方差分析发现PAHs和OCPs在2种方法中的分布特征无显著差异。Xu等[73]采用大流量主动采样和SPMD被动采样,采集中国大连市的大气样品,发现主动和被动中的PCBs同系物分布、dl-PCBs和毒性当量的主要贡献者是类似的。Zhu等[74]采用大流量主动采样器和SPMD被动采样器采集中国大连城市的大气样品,分析其中的PAHs,发现主动和被动中气相PAHs的主要贡献者是类似的。但是也有文献发现,由于受到环境等因素的影响,主动采样和被动采样所得的结果可能存在差别。Ren等[67]采用大流量主动采样和PUF-PAS对中国北方工业城市唐山空气中PCDD/Fs的监测发现,两者的结果存在差异,推测可能是随机排放源和气象条件等不确定因素导致的结果。总体来说,主动采样和被动采样的结果是具有可比性的,对于研究大气中的POPs,被动大气采样是有效、可靠的补充工具。

3 挑战与展望(Challenge and prospect)

目前对大气中POPs的采样方法研究日渐成熟,应用相关技术广泛开展了各项研究。但依然存在着不少问题和困难,如使用不同吸附材料对大气中POPs采集效率进行对比研究的文献报道很少,新型吸附材料、新型采样器的研发也有待加强,以满足多种POPs监测的实际需求;不同类型AAS和PAS采样方法的对比研究,TSP和PM10监测数据间的可对比性研究还需进一步开展,才能更加深入地科学评估监测数据的一致性;此外,列入斯德哥尔摩公约的POPs已达26种,由于不同POPs之间挥发性及降解等特性差异较大,缺少普适性的采样方法,且不同国家履约所用的POPs采样方法还存在差异,监测数据的可比对性影响了履约成效评估,因此建立统一标准化的模型工具或者相关的校正方法研究也亟待深入开展。

[1] 张干, 刘向. 大气持久性有机污染物(POPs)被动采样[J]. 化学进展, 2009, 21(2): 297-306

Zhang G, Liu X. Passive atmospheric sampling of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) [J]. Progress in Chemistry, 2009, 21(2): 297-306 (in Chinese)

[2] Clarkson P J, Larrazabal-Moya D, Staton I, et al. The use of tree bark as a passive sampler for polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and furans [J]. International Journal of Environmental & Analytical Chemistry, 2002, 82(11-12): 843-850

[3] Wennrich L, Popp P, Hafner C. Novel integrative passive samplers for the long-term monitoring of semivolatile organic air pollutants [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2002, 4(3): 371-376

[4] Klánová J, Kohoutek J, Hamplová L, et al. Passive air sampler as a tool for long-term air pollution monitoring: Part 1. Performance assessment for seasonal and spatial variations [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(2): 393-405

[5] Hazrati S, Harrad S. Calibration of polyurethane foam (PUF) disk passive air samplers for quantitative measurement of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs): Factors influencing sampling rates [J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 67(3): 448-455

[6] Genualdi S, Lee S C, Shoeib M, et al. Global pilot study of legacy and emerging persistent organic pollutants using sorbent-impregnated polyurethane foam disk passive air samplers [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(14): 5534-5539

[7] Harner T, Pozo K, Gouin T, et al. Global pilot study for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) using PUF disk passive air samplers [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(2): 445-452

[8] Lee S C, Harner T, Pozo K, et al. Polychlorinated naphthalenes in the global atmospheric passive sampling (GAPS) study [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(8): 2680-2687

[9] Pozo K, Harner T, Lee S C, et al. Seasonally resolved concentrations of persistent organic pollutants in the global atmosphere from the first year of the GAPS study [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(3): 796-803

[10] Leslie H, Boer J D, Bavel B V, et al. Towards comparable POPs data worldwide with global monitoring data and analytical capacity building in Africa, Central and Latin America, and the South Pacific [J]. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 46: 85-97

[11] Klánová J, Harner T. The challenge of producing reliable results under highly variable conditions and the role of passive air samplers in the Global Monitoring Plan [J]. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 46: 139-149

[12] Bogdal C, Scheringer M, Abad E, et al. Worldwide distribution of persistent organic pollutants in air, including results of air monitoring by passive air sampling in five continents [J]. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 46: 150-161

[13] Choi S D, Baek S Y, Chang Y S, et al. Passive air sampling of polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides at the Korean Arctic and Antarctic research stations: Implications for long-range transport and local pollution [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(19): 7125-7131

[14] 张颖, 吕天峰, 梁宵, 等. 主动采样技术在中国大气POPs监测中的应用[J]. 中国环境监测, 2009, 25(1): 14-18

Zhang Y, Lv T F, Liang X, et al. Application of active air sampling in monitoring of persistent organic pollutions in atmosphere of China [J]. Environmental Monitoring in China, 2009, 25(1): 14-18(in Chinese)

[15] Raun L H, Correa O, Rifai H, et al. Statistical investigation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in the ambient air of Houston, Texas [J]. Chemosphere, 2005, 60(7): 973-989

[16] Cindoruk S S, Tasdemir Y. Ambient air levels and trends of polychlorinated biphenyls at four different sites [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2010, 59(4): 542-554

[17] Ma J, Chen Z, Wu M, et al. Airborne PM2.5/PM10-associated chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their parent compounds in a suburban area in Shanghai, China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(14): 7615-7623

[18] Chrysikou L P, Gemenetzis P G, Samara C A. Wintertime size distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in the urban environment: Street- vs rooftop-level measurements [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2009, 43(2): 290-300

[19] Chrysikou L P, Samara C A. Seasonal variation of the size distribution of urban particulate matter and associated organic pollutants in the ambient air [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2009, 43(30): 4557-4569

[20] Kaupp H, McLachlan M S. Distribution of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) within the full size range of atmospheric particles [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2000, 34(1): 73-83

[21] Oh J E, Chang Y S, Kim E J, et al. Distribution of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) in different sizes of airborne particles [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2002, 36(32): 5109-5117

[22] Chao M R, Hu C W, Ma H W, et al. Size distribution of particle-bound polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in the ambient air of a municipal incinerator [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2003, 37(35): 4945-4954

[23] Zhang X, Zhu Q Q, Dong S J, et al. Particle size distributions of PCDD/Fs and PBDD/Fs in ambient air in a suburban area in Beijing, China [J]. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2015, 15(5): 1933-1943

[24] Chien S M, Huang Y J, Chuang S C, et al. Effects of biodiesel blending on particulate and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions in nano/ultrafine/fine/coarse ranges from diesel engine [J]. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2009, 9(1): 18-31

[25] Yu H,Yu J Z. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban atmosphere of Guangzhou, China: Size distribution characteristics and size-resolved gas-particle partitioning [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2012, 54: 194-200

[26] Chuang K Y, Lai C H, Peng Y P, et al. Characteristics of particle-bound polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) in atmosphere used in carbon black feeding process at a tire manufacturing plant [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2015, 22(24): 19451-19460

[27] Zhang B, Zhang L F, Wu J J, et al. An active sampler for monitoring polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and furans in ambient air [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2011, 87(1): 1-5

[28] Melymuk L, Bohlin P, Sanka O, et al. Current challenges in air sampling of semivolatile organic contaminants: Sampling artifacts and their influence on data comparability [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(24): 14077-14091

[29] Mari M, Schuhmacher M, Feliubadalo J, et al. Air concentrations of PCDD/Fs, PCBs and PCNs using active and passive air samplers [J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 70(9): 1637-1643

[30] Alegria H A, Wong F, Jantunen L M, et al. Organochlorine pesticides and PCBs in air of southern México (2002-2004) [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2008, 42(38): 8810-8818

[31] Xiao H, Hung H, Harner T, et al. Field testing a flow-through sampler for semivolatile organic compounds in air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(8): 2970-2975

[32] 刘碧莲, 吴水平, 杨冰玉, 等. 大气中多环芳烃气/粒分配的不确定性分析[J]. 环境科学, 2011, 32(9): 2794-2799

Liu B L, Wu S P, Yang B Y, et al. Uncertainty analysis of gas/particle partitioning of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Environmental Science, 2011, 32(9): 2794-2799 (in Chinese)

[33] Galarneau E, Harner T, Shoeib M, et al. A preliminary investigation of sorbent-impregnated filters (SIFs) as an alternative to polyurethane foam (PUF) for sampling gas-phase semivolatile organic compounds in air [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2006, 40(29): 5734-5740

[34] Jin G Z, Kim S M, Lee S Y, et al. Levels and potential sources of atmospheric organochlorine pesticides at Korea background sites [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2013, 68: 333-342

[35] Yagoh H, Murayama H, Suzuki T, et al. Simultaneous monitoring method of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and persistent organic pollutants in the atmosphere using activated carbon fiber filter paper [J]. Analytical Sciences, 2006, 22(4): 583-590

[36] Hippelein M, Kaupp H, Dörr G, et al. Baseline contamination assessment for a new resource recovery facility in Germany part III: PCDD/Fs, HCB, and PCBs in cow's milk [J]. Chemosphere, 1996, 32(8): 1617-1622

[37] Wallenhorst T, Krauβ P, Hagenmaier H. PCDD/F in ambient air and deposition in Baden-Württemberg, Germany [J]. Chemosphere, 1997, 34(5): 1369-1378

[38] Umlauf G, Christoph E H, Eisenreich S J, et al. Seasonality of PCDD/Fs in the ambient air of Malopolska region, southern Poland [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2010, 17(2): 462-469

[39] Cheng P S, Hsu M S, Ma E, et al. Levels of PCDD/Fs in ambient air and soil in the vicinity of a municipal solid waste incinerator in Hsinchu [J]. Chemosphere, 2003, 52(9): 1389-1396

[40] Coleman P J, Lee R G, Alcock R E, et al. Observations on PAH, PCB, and PCDD/F trends in UK urban air, 1991-1995 [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1997, 31(7): 2120-2124

[41] Vilavert L, Nadal M, Schuhmacher M, et al. Seasonal surveillance of airborne PCDD/Fs, PCBs and PCNs using passive samplers to assess human health risks [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 466-467: 733-740

[42] Qin S T, Zhu X H, Wang W, et al. Concentrations and gas-particle partitioning of PCDD/Fs in the urban air of Dalian, China [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2012, 57(26): 3442-3451

[43] Wania F, Shen L, Lei Y D, et al. Development and calibration of a resin-based passive sampling system for monitoring persistent organic pollutants in the atmosphere [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2003, 37(7): 1352-1359

[44] Kot-Wasik A, Zabiegala B, Urbanowicz M, et al. Advances in passive sampling in environmental studies [J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2007, 602(2): 141-163

[45] 赵玉丽, 杨利民, 王秋泉. 植物—实时富集大气持久性有机污染物的被动采样平台[J]. 环境化学, 2005, 24(3): 233-240

Zhao Y L, Yang L M, Wang Q Q. Vegetation as a passive sampler for air pollution monbioring of persistent organic pollutants[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2005, 24(3): 233-240 (in Chinese)

[46] Shoeib M, Harner T. Characterization and comparison of three passive air samplers for persistent organic pollutants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2002, 36(19): 4142-4151

[47] Li X, Li Y, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of atmospheric sources of PCDD/Fs, PCBs and PBDEs around a steel industrial complex in northeast China using passive air samplers [J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 84(7): 957-963

[48] Moussaoui Y, Tuduri L, Kerchich Y, et al. Atmospheric concentrations of PCDD/Fs, dl-PCBs and some pesticides in northern Algeria using passive air sampling [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 88(3): 270-277

[49] Shoeib M, Harner T, Lee S C, et al. Sorbent-impregnated polyurethane foam disk for passive air sampling of volatile fluorinated chemicals [J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2008, 80(3): 675-682

[50] Koblizkova M, Genualdi S, Lee S C, et al. Application of sorbent impregnated polyurethane foam (SIP) disk passive air samplers for investigating organochlorine pesticides and polybrominated diphenyl ethers at the global scale [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 46(1): 391-396

[51] Shen L, Wania F, Lei Y D, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the North American atmosphere [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(2): 434-444

[52] Ockenden W A, Prest H F, Thomas G O, et al. Passive air sampling of PCBs: Field calculation of atmospheric sampling rates by triolein-containing semipermeable membrane devices [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1998, 32(10): 1538-1543

[53] Ockenden W A, Corrigan B P, Howsam M, et al. Further developments in the use of semipermeable membrane devices as passive air samplers: Application to PCBs [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2001, 35(22): 4536-4543

[54] Esen F. Development of a passive sampling device using polyurethane foam (PUF) to measure polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) near landfills [J]. Environmental Forensics, 2013, 14(1): 1-8

[55] Xiao H, Hung H, Harner T, et al. A flow-through sampler for semivolatile organic compounds in air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(1): 250-256

[56] Tao S, Cao J, Wang W T, et al. A passive sampler with improved performance for collecting gaseous and particulate phase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43: 4124-4129

[57] Tao S, Liu Y N, Lang C, et al. A directional passive air sampler for monitoring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in air mass [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2008, 156(2): 435-441

[58] Pozo K, Harner T, Shoeib M, et al. Passive-sampler derived air concentrations of persistent organic pollutants on a north-south transect in Chile [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004, 38(24): 6529-6537

[59] Thomas J, Holsen T M, Dhaniyala S. Computational fluid dynamic modeling of two passive samplers [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(2): 384-392

[60] Pozo K, Harner T, Wania F, et al. Toward a global network for persistent organic pollutants in air: Results from the GAPS study [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(16): 4867-4873

[61] Huckins J N, Tubergen M W, Manuweera G K. Semipermeable membrane devices containing model lipid: A new approach to monitoring the bioavaiiability of lipophilic contaminants and estimating their bioconcentration potential [J]. Chemosphere, 1990, 20(5): 533-552

[62] Harner T, Farrar N J, Shoeib M, et al. Characterization of polymer-coated glass as a passive air sampler for persistent organic pollutants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2003, 37: 2486-2493

[63] Bartkow M E, Jones K C, Kennedy K E, et al. Evaluation of performance reference compounds in polyethylene-based passive air samplers [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(2): 365-370

[64] Martínez K, Abad E, Gustems L, et al. PCDD/Fs in ambient air: TSP and PM10sampler comparison [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2006, 40(3): 567-573

[65] 杨复沫, 贺克斌, 马永亮, 等. 北京PM2.5浓度的变化特征及其与PM10、TSP的关系[J]. 中国环境科学, 2002, 22(6): 506-510

Yang F M, He K B, Ma Y L, et al. Variation characteristics of PM2.5concentration and its relationship with PM10and TSP in Beijing [J]. China Environmental Science, 2002, 22(6): 506-510 (in Chinese)

[67] Ren Z Y, Zhang B, Lu P, et al. Characteristics of air pollution by polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in the typical industrial areas of Tangshan City, China [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2011, 23(2): 228-235

[68] Aristizabal B H, Gonzalez C M, Morales L, et al. Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofuran in urban air of an Andean city [J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 85(2): 170-178

[69] Hayward S J, Gouin T, Wania F. Comparison of four active and passive sampling techniques for pesticides in air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(9): 3410-3416

[70] Gouin T, Harner T, Blanchard P, et al. Passive and active air samplers as complementary methods for investigating persistent organic pollutants in the Great Lakes basin [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(23): 9115-9122

[71] Levy W, Henkelmann B, Pfister G, et al. Monitoring of PCDD/Fs in a mountain forest by means of active and passive sampling [J]. Environmental Research, 2007, 105(3): 300-306

[72] He J, Balasubramanian R. A comparative evaluation of passive and active samplers for measurements of gaseous semi-volatile organic compounds in the tropical atmosphere [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2010, 44(7): 884-891

[73] Xu Q, Zhu X H, Henkelmann B, et al. Simultaneous monitoring of PCB profiles in the urban air of Dalian, China with active and passive samplings [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2013, 25(1): 133-143

[74] Zhu X H, Zhou C Z, Henkelmann B, et al. Monitoring of PAHs profiles in the urban air of Dalian, China with active high-volume sampler and semipermeable membrane devices [J]. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2013, 33(3): 265-288

◆

Progress on the Sampling Techniques of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Atmosphere

Zhu Qingqing1,2, Liu Guorui1,2, Zhang Xian1,2, Dong Shujun1,2, Gao Lirong1,2, Zheng Minghui1,2,*

1. State Key Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Received 29 November 2015 accepted 6 January 2016

Atmosphere is one of the core matrices for global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs). The atmospheric POPs sampling techniques are important for accurately measuring the levels of POPs in the air, which have been rapidly developed in recent years. In this paper, two types of active air sampling (AAS) and passive air sampling (PAS) were reviewed. The development of new adsorbent materials was summarized and the characteristics of different types of samplers were discussed. Moreover, the monitoring data obtained by using different sampling techniques were compared and some issues of the data comparability were proposed.

persistent organic pollutants; atmosphere; active air sampling; passive air sampling

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20151129003

国家自然科学基金(21361140359,91543108)

朱青青(1990-),女,博士研究生,研究方向为环境科学,E-mail: qingqzhu@126.com

*通讯作者(Corresponding author), E-mail: zhengmh@rcees.ac.cn

2015-11-29 录用日期:2016-01-06

1673-5897(2016)2-050-11

X171.5

A

简介:郑明辉(1962—),男,博士,研究员,主要研究方向为环境化学。

朱青青, 刘国瑞, 张宪, 等. 大气中持久性有机污染物的采样技术进展[J]. 生态毒理学报,2016, 11(2): 50-60

Zhu Q Q, Liu G R, Zhang X, et al. Progress on the sampling techniques of persistent organic pollutants in atmosphere [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2016, 11(2): 50-60 (in Chinese)