“婴儿潮”一代无处安放的传家宝

By+Samantha+Bronkar

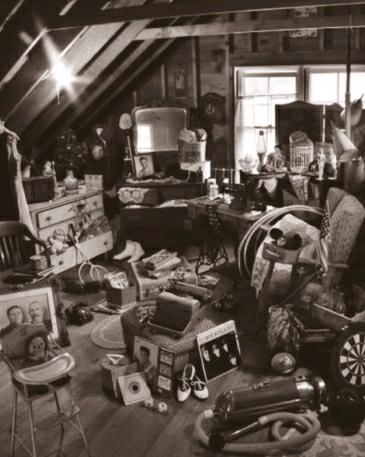

Two hundred stuffed animals, two violins, and a 7-1/2 foot-tall Christmas tree: That was just a corner of the possessions Rosalie and Bill Kelleher accumulated over their 47-year marriage.2 And, they realized, it was about 199 stuffed animals more than their two grown children wanted.

Going from a four-bedroom house in New Bedford, Mass.—with an attic stuffed full of paper stacked four-feet tall—to a 1,300-square-foot apartment took six years of winnowing, sorting, shredding, and shlepping stuff to donation centers.3

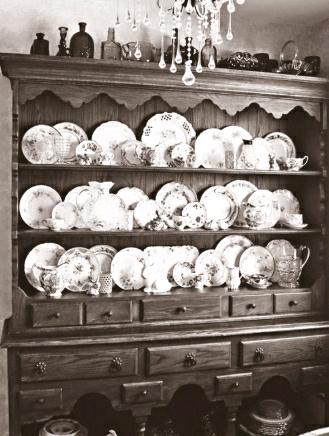

Among the possessions the Kellehers are keeping are three hutches(橱柜)—one that belonged to his mother, one that belonged to her mother, and one that they purchased together 35 years ago. One shelf is carefully lined with4 teacups Rosalie collected during her world travels. Another houses a delicate tea set(茶具)from Japan, a gift her mother received on her wedding day.

“We really dont need them,” she admits.

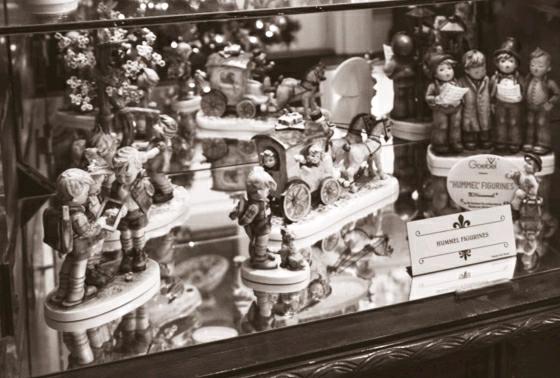

That refrain is becoming a common one as baby boomers begin to downsize and discover (as many generations before them have) that their children do not want their stuff.5 In fact, they recoil in something close to horror at the thought of trying to find room for the collections of Hummels; the Thomas Kinkade paintings; the complete sets of fine china and crystal, carefully preserved and brought out at holiday meals.6

For their parents, to have a lifetime of carefully chosen treasures dismissed as garage-sale fodder can be downright painful.7

“When people try to throw something away, they feel like they are losing personal history, losing a bit of themselves, losing a little of their identity, and they fear if they get rid of it theyll never have that same experience again,” says Randy Frost, a psychology professor at Smith College and coauthor of Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things8.

While every generation has its turn with an attachment for antiques or nostalgia for outdated technology, todays tech-heavy culture shows few signs of trading in its sleek, modern designs for dark furniture or knick-knacks from bygone eras.9 And many younger families see trips, vacations, and photos as the repository(貯藏室,宝库)of family memories—not shelves full of mementoes(纪念品).

“Their kids oftentimes have homes already, they have families already, they have furnishings already,” says Kate Grondin, owner of Home Transition Resource in Adover, Mass. Ms. Grondin is part of a senior move-management industry that will pack, move, unpack, sell, and donate clients things as they move to smaller homes.endprint

There are other signs that the next stop for those attic treasures may be the town dump(垃圾场). The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, by Marie Kondo with a specific process for getting rid of things, has sold 1.5 million copies since 2014 in the United States. Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, otherwise known as The Minimalists(极简主义者), have published several bestselling memoirs(回忆录), produced Minimalism: A Documentary About the Important Things in 2016, and traveled across the US in their “Less is Now Tour 2017.”

When a pile of possessions has come to embody a sense of identity—or even what someone could yet become—its not always easy to figure out what should stay and what should go.10

Dr. Frost recounts the story of a woman who “saved all of these cookbooks and all these recipes,” even though she didnt really know how to cook. “If she were to try to throw some of that stuff away,” he explains, “that [removes] the opportunity for her to become the cook she thinks shed like to be. In a sense, its removing a potential identity for her.”

“You know you dont have space for it”

Judy Maguire of Andover, Mass., and her siblings helped their mother move to an assisted living facility(療养院)after their father died. They carefully selected some furniture and photographs that would make her feel at home.

But then they faced the difficult task of figuring out which heirlooms(传家宝)to keep for themselves.

“We were all pretty sentimental(多愁善感的),” Ms. Maguire admits.

She recalls the siblings arguing over one particular piece—not over who would get it, but how to stop one sister from keeping what Maguire describes as a “big, hideous piece of furniture.”11

“I said, ‘You know you dont have the space for it. You dont really need that. And she said, ‘I know... I just cant let go of it, ” Maguire says.

They ended up donating the table.

Dr. Frost suggests posing a simple question for those going through this process: “How does this object fit into your life?”

The Kellehers created staging sections(物品暂存区)in their house for specific items, using their kids vacant rooms, the living room, and the sunroom. Eventually, all of the leftover items to be taken away fit into the downstairs rec room(娱乐室= recreation room), half of which had been filled with empty cardboard boxes being saved for some potential use.

Others have found that parting ways with12 familiar possessions actually brings a sense of freedom.endprint

“Its like hes still in college”

Carolyn Ledewitz of Cambridge, Mass., discovered that her son didnt want anything when she downsized. “My son drove all the way up from New York City to go through13 his childhood things. I was appalled when he just grabbed them out of the boxes and dumped them into the trash,” she says.14

Ms. Ledewitz describes her 40-something sons apartment as “so sparse(稀疏的,不充足的)—its like hes still in college. He doesnt have a single picture on the wall” of his Manhattan apartment, she says.

But Ledewitz ended up adopting some of her sons attitude to achieve her goal of living in a sleek city condo(公寓楼里的一套住宅)in Bostons Seaport district. She and her husband made the transition in two steps. First, they downsized from their ranch(大牧场)home in Springfield, Mass., where they had lived for 33 years into a three-story town home nearby.

“I had a china cabinet(瓷器柜)in my dining room with all my wedding presents...my mothers sugar bowl, the silver. I just loved it. I would look at it every day,” she says.

Ultimately, she says, the lifestyle she wanted outweighed15 the things she thought she cherished.

“Over the years, when you cant hand it down16, you have to let it go,” she says. She and her husband are now living out their urban dream.

That said, even professionals are not immune to temptation: Of all their late fathers possessions, Nan Hayes and her siblings found themselves squabbling about a large statue of a conquistador.17 (Ultimately, the brother whose vehicle could transport it lugged home the booty.18)

Ms. Hayes, the business development director of Caring Transitions, spent 10 years as a transition specialist helping individuals downsize their possessions and homes.

“The part of the job I miss the most,” she says, is seeing her clients “so much happier to be where they are19 because they know its where they need to be.”

“Downsizing was challenging, but it was good for my husband and me,” Ledewitz admits. “Its been so nice not worrying about all that stuff. Life is much simpler without all that maintenance(維护,收理).”

1. boomer parents: 指美国婴儿潮(第二次世界大战后1946—1964年间的生育高峰)时期出生的一代人,他们身为父母已达到退休年龄,他们的孩子也基本长大成人。

2. stuffed animal: 毛绒玩具;accumulate: 积攒。

3. 他们原先住在马萨诸塞州新贝德福德的一个四居室,房子的阁楼里堆满了旧印刷品(堆了一米多高),后来搬至一间120多平方米的公寓楼,在那里他们花了六年时间(处理这些旧印刷品):筛选、分拣、粉碎,或是运到捐赠中心。attic: 阁楼;stack: 堆放;winnow: 筛选,选取;shred: 用碎纸机切碎(文件);shlep(p): //〈美口〉拖拽(重物),亦作schlep(p)。endprint

4. line with: 沿着……排列成行。

5.“婴儿潮”一代在开始削减闲置物时才意识到(就像世世代代的父母都经历过的那样),孩子们不想要父母留传下来的东西,并会再三强调“我真的不需要”。refrain: n. 一再重复的话(或想法);downsize: 使……(规模)变小。

6. 实际上,子女们一想到要找地方安置成套的喜姆娃娃、托马斯·金凯德系列画作和一套套精心保存、只有节日才会拿出来使用的细瓷和水晶餐具就发怵了。recoil in horror: 因害怕往后缩,畏缩;Hummels: 喜姆娃娃,是德国著名的手工瓷偶,所有娃娃形象均来自德国一位名为喜姆的修女的画稿;Thomas Kinkade: 托马斯·金凯德(1958—2012),美国画家,以传统美国风景画著称;fine china:细瓷。

7. dismiss as:(因认为……不重要而)不予考虑,抛弃;garage-sale: 在私家车库进行的家中闲置旧货交易;fodder: 素材,这里指被当成闲置旧货出售的对象;downright: 彻头彻尾地,十足地。

8. Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things:《囤积是种病:别让杂物堵住你的幸福》,是史密斯学院心理学教授、强迫症研究方面的专家兰迪·弗罗斯特的代表作。compulsive: 强迫性的;hoard: 贮藏,囤积。

9. 虽说每代人天生都会舍不得老物件或是怀念已被淘汰的技术,但在如今科技产品层出不穷的文化背景下,几乎看不到有人用设计新颖、现代化的产品换取颜色暗沉的旧家具或是过去的小玩意的。have ones / a turn:(某人)天性具有……;nostalgia: 怀旧;sleek: 时髦的;knick-knack:小摆设,小玩意儿(尤指小而无用的纪念品);bygone: 以前的,过去的。

10. 人们收集的物品往往能体现出他对自己现有身份(甚至将来可能成为的人)的认同感,因此判断该留下什么,该丢掉什么,并不是一件容易的事。embody:使……具体化,具体体现。

11. 马奎尔夫人仍记得她和兄弟姐妹们曾因一件东西起了争执,倒不是为了争夺它的所属权,而是她想劝说妹妹丢掉那件她眼中“又笨重又難看”的旧家具。hideous: // 丑得不忍目睹的,令人憎厌的。

12. part ways with: 与……分道扬镳。

13. go through: 彻底检查,仔细搜查。

14. appalled: 惊骇的;dump: 丢弃,扔掉。

15. outweigh: 比……重要。

16. hand down: 把(习惯、传家物等)传给后代。

17. immune: 不受影响的,有免疫力的;late: 已故的,(尤指)新近去世的;squabble(为琐事)争吵,发生口角;conquistador: //(尤指16世纪在墨西哥、中美洲、南美洲地区的)西班牙征服者。

18. lug: (用力)拖,拉;booty: 战利品。

19. to be where they are: 指顾客回到清理过闲置物的家后。endprint