Management of massive fistula bleeding after endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using hemostatic forceps:A case report

Nan Ge, Si-Yu Sun

Nan Ge, Si-Yu Sun, Endoscopy Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University,Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China

Abstract

Key words: Pancreatic fluid collections; Endoscopic ultrasound; Drainage; Hemorrhage;Case report

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage is the optimal method for the treatment of pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs), and is associated with ease, safety,and efficiency[1-5].Bleeding is one of the main procedure-related complications; the incidence is low but difficult to manage and often requires surgery or radiologicguided embolization[6].Herein we report the successful management of massive fistula bleeding during EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using hemostatic forceps.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complains

A 42-year-old man presented for evaluation of abdominal pain and distention for approximately 2 wk.

History of past illness

The patient has a long-term history of alcohol consumption.

Imaging examinations

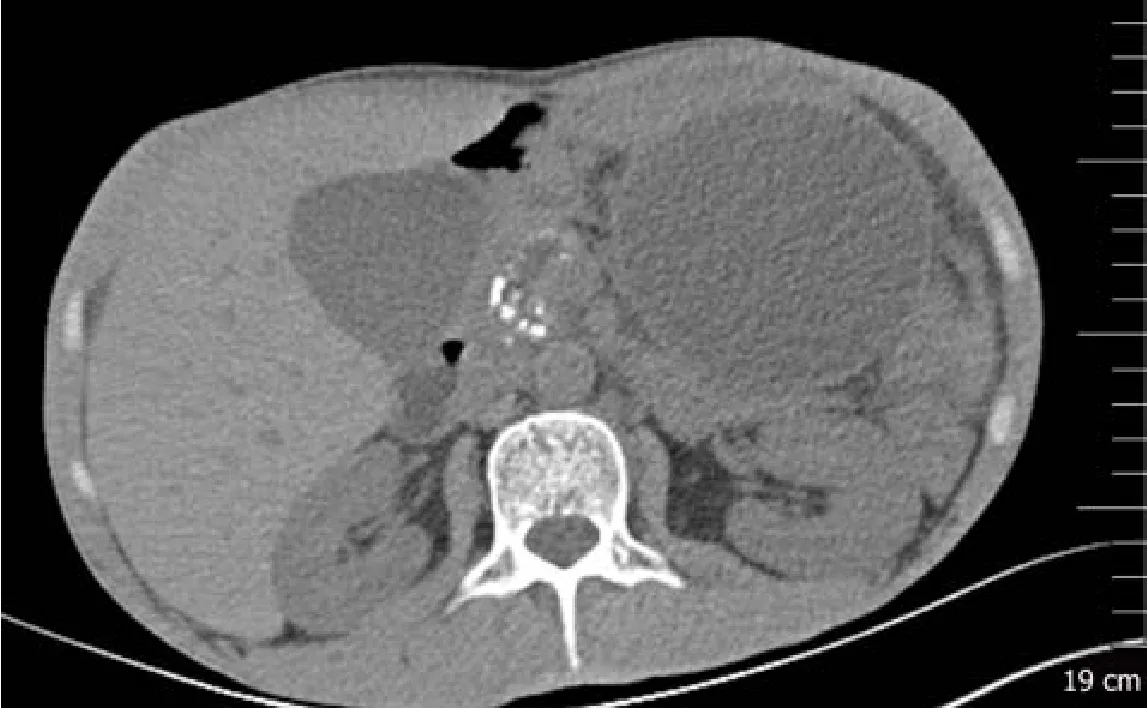

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed atrophy of the pancreatic parenchyma and dilation of the main pancreatic duct with multiple stones.A pancreatic pseudocyst was located in the tail of the pancreas, measuring 9.8 cm × 8.0 cm.Varicose veins were also found around the fundus of the stomach (Figure 1).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatic pseudocyst.

TREATMENT

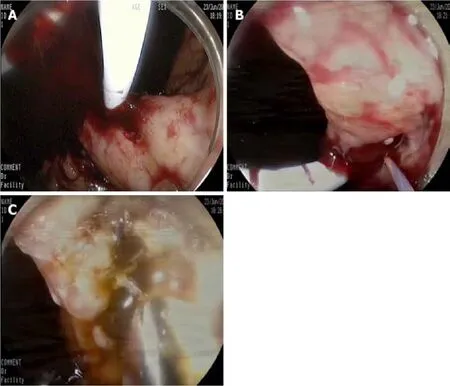

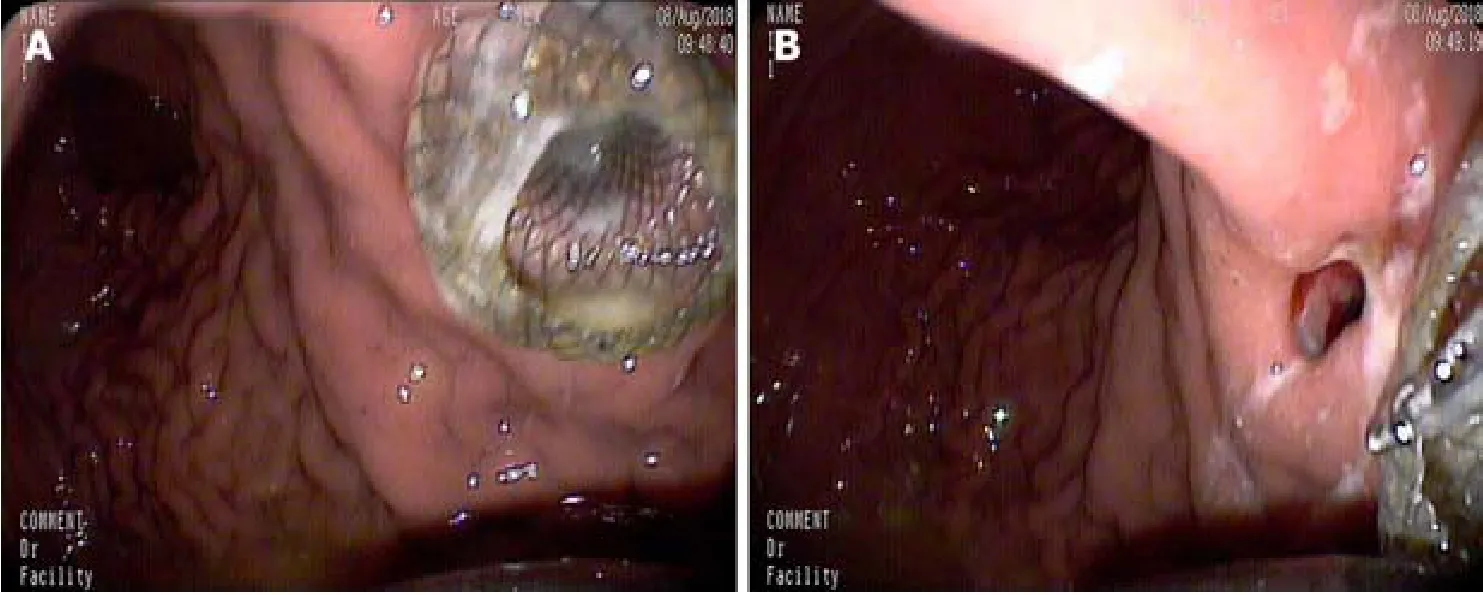

An EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy was performed.A longitudinal echoendoscope(PENTAXEG3870UT; Pentax Corporation, Takyo, Japan) with a 3.8-mm working channel accessible to a 10 Fr stent was used.Color Doppler was used to identify and avoid interposing vessels during puncture.An EchoTip Ultra endoscopic ultrasound needle (19-gauge; Boston Scientific Corp., United States) was introduced via the working channel of the echoendoscope, and the PFC was punctured under EUS guidance (Figure 2).A brown cystic fluid sample was aspirated and sent to determine the amylase level, as well as for other biochemical analyses.A guidewire (0.035 inch/480 mm; Boston Scientific, United States) was inserted into the cystic cavity.A cystotome (10 Fr; Wilson-Cook Medic, United States) was delivered to the dilated needle path and followed with a 10-mm balloon dilator.A 10-Fr plastic double-pigtail stent (Wilson-Cook Medic) was placed.After the stent placement, massive bleeding was noted from the fistula (Figure 3A).Under EUS, the site of bleeding was difficult to locate and blood began to fill the stomach cavity.We withdrew the EUS and introduced a gastrointestinal endoscope (3.2-mm working channel; Pentax Corporation) with a transparent cap attached.The bleeding vessel was viewed within the fistula (Figure 3B).Hemostatic forceps were introduced and the vessel was grasped until the bleeding stopped, then high-frequency electrocoagulation was performed.Hemostasis was successfully achieved (Figure 3C).A lumen-apposing metal stent (12 mm/25 mm, 16 mm/35 mm; Micro-Tech/Nan Jing Co., Ltd., China)was placed for the pancreatic pseudocyst drainage.

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography image revealing atrophy of the pancreatic parenchyma and dilation of the main pancreatic duct with multiple stones.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

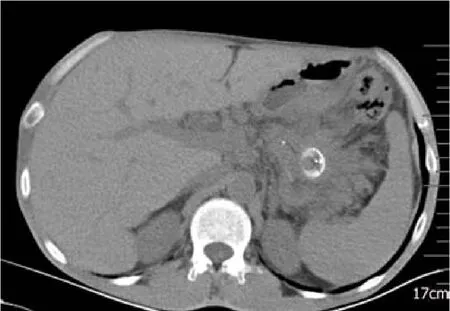

After the procedure, the patient remained hemodynamically stable, received standard care and antibiotics, and had no drop in hemoglobin during a 3-day hospital stay.A follow-up abdominal CT scan 1 month later showed almost complete resolution of the PFC (Figure 4), and the stent was removed (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Ultrasound-guided drainage is the first-line modality for drainage of symptomatic PFCs.The overall clinical success rate is 90.5%-100%; the adverse effect rate is 98.0%-23.8%, mainly including hemorrhage, perforation, secondary infection, and stent migration[7-11].Procedure-related bleeding reportedly occurs in 1%-2% of cases during EUS-guided drainage of PFCs.The use of EUS may help to reduce the risk of bleeding by visualizing intervened vessels.One prospective study reported a 13% bleeding rate with conventional endoscopic drainage, compared to no bleeding with EUS-guided interventions[12]; however, even with EUS guidance, bleeding remains an important adverse event[13].Varadarajuluet al[7]also reported that bleeding occurred in a patient with underlying acquired factor VIII inhibitors.Also, straight biliary fully-covered self-expandable metal stent possibly increases the risk of delayed bleeding, in which case endoscopic intervention may be limited.Stent erosion of the gastric wall can occur during esophagogastroduodenoscopy.Collateral vessel bleeding can also occur during fistula creation and is often successfully managed conservatively.The bleeding caused by splenic artery pseudoaneurysms are often life-threatening[6].In our case, the vessel injury during puncture, which was missed during EUS scanning, was the cause of bleeding.

As reported, there are three endoscopic interventions to manage bleeding during the procedure, as follows:(1) Fistula bleeding can be compressed by a balloon dilator,which is effective when the bleeding is not severe[14]; (2) A fully-covered selfexpandable metal stent is delivered directly to continuously compress the fistula; and(3) Wanget al[14]reported using a bi-flanged self-expandable metal stent to stop bleeding in the needle path by external compression at the puncture site from stent expansion.In our case, the needle path was dilated using a 1-cm balloon, which permitted clear visualization of the needle path and identification of the bleeding vessel.If the needle path was not fully dilated, the bleeding vessel would not be detected and a fully covered metal stent may be considered.In our case, the bleeding vessel was ruptured and direct hemostasis was considered before balloon or stent compression.

Figure 2 The pancreatic fluid collection was punctured by fine-needle aspiration under endoscopic ultrasound guidance.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, bleeding vessel grasp and coagulation may represent a successful treatment for a fistula hemorrhage during EUS-guided drainage for a PFC, which may be tried before application of balloon or stent compression.

Figure 3 Endoscopic ultrasound images.

Figure 4 A follow-up abdominal computed tomography scan 1 mo later showed almost complete resolution of the pancreatic fluid collection.

Figure 5 The placed metal stent (A) and the stent was removed (B).

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年23期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年23期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Overview of organic anion transporters and organic anion transporter polypeptides and their roles in the liver

- Value of early diagnosis of sepsis complicated with acute kidney injury by renal contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- Value of elastography point quantification in improving the diagnostic accuracy of early diabetic kidney disease

- Resection of recurrent third branchial cleft fistulas assisted by flexible pharyngotomy

- Therapeutic efficacy of acupuncture combined with neuromuscular joint facilitation in treatment of hemiplegic shoulder pain

- Comparison of intra-articular injection of parecoxib vs oral administration of celecoxib for the clinical efficacy in the treatment of early knee osteoarthritis