Do Unfamiliar Text Orientations Affect Transposed-Letter Word Recognition with Readers from Different Language Backgrounds?

Lingling Li & Guanjie Jia

Soochow University, China

Abstract Although accurate coding of letter or character identities and positions is very important for word recognition, it is well established that transposed-letter (TL) words or transposedcharacter (TC) words do not influence word processing. However, most previous studies mainly examined TL words presented horizontally from left to right and considered less whether the same effect would occur with unusual text orientations. This paper examines the issue of whether unfamiliar text orientations would affect TL word processing when words are presented vertically from top to bottom or bottom to top, horizontally from right to left, or extremely rotated by 90° or 180°. Moreover, this paper also looks at the issue of whether readers’ previous language backgrounds (monolingual vs. bilingual) and language-specific text orientations (single reading direction vs. multiple text orientations) influence TL word processing in unfamiliar circumstances. Based on the most recent evidence, this paper is in favor of the abstract letter units account which proposes that the basis of orthographic coding in skilled readers is abstract representations. Furthermore, a reconsideration from a perspective of Saussure’s conceptions of the signified and the signifier is developed. In the end, two main directions of future research are suggested: first, to the realm of bilingual TL study, with the aim to specify the key reasons why bilinguals demonstrate mixed results under unfamiliar text orientations and second, to the realm of sentence reading, in order to specify how orthographic information can be processed across longer text units other than words.

Keywords: text orientation, transposed letter, priming effects, abstract representation

1. Introduction

Languages are essentially and primarily symbolic systems, involving both auditory (i.e., sound) and visual (i.e., written) symbols that carry complex information. While spoken language is a universal competence which can be commonly acquired by human beings without systematic instruction, written language is a skill that must be taught to each generation of children. As an important invention of human society, written words can render language visible by way of transforming auditory information into visual symbols. While spoken words are ephemeral, written words are concrete and longstanding. Thus, with written words, human societies have accumulated, inherited and spread knowledge and cultures for thousands of years.

As one of the most complex skills learned by humans, reading involves complex cognitive processes (Liu & Wang, 2016). A series of visual and perceptual activities take place during reading, one of which is to encode and decode linguistic symbols. To recognize a word successfully, readers need to encode the identity of each of the component letters or characters and the order in which they appear. Take the word JUDGE for example. It is demanded to encode and decode each component letter of JUDGE and their respective position in recognition, that is, JUDGE contains letters of j/u/d/g/e which are sequenced in j-u-d-g-e. Otherwise, readers would not be able to distinguish diary from dairy or 蜂蜜 (honey) from 蜜蜂 (bee) as they contain exactly the same letters or characters. Therefore, a word’s coding information is mainly derived from letter identities and letter positions, and their coding plays a crucial role in word recognition and reading, occupying the key interface between lower-level visual input and higher-level linguistic processing (Grainger, 2018; Yang & Lupker, 2019).

However, prior researchers found that letter position is not absolutely strict, and transposed-letter (TL) nonwords can be easily misperceived as real words, as indicated by the famous “Cambridge University effect” :

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be in the rghit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by it slef but the wrod as a wlohe. (Velan & Frost, 2007)

It is also well established in literature that in masked priming lexical decision experiments (Forster & Davis, 1984), a word is recognized more effectively when it is primed (i.e., preceded) by a transposed letter nonword than by a substituted letter (SL) nonword. For example, when JUDGE follows the TL nonword “jugde” which is created by changing the orders of letter “d” and “g” in JUDGE, it is recognized faster than when it follows the SL nonword “junpe” which is created by replacing the letters “d” and “g” with “n” and “p” (Perea & Lupker, 2003). The time difference from responses for the same word (JUDGE) following TL nonwords (jugde) versus SL nonwords (junpe) is calledTransposed-letter (TL) priming effects, which has been repeatedly reported in various languages, whether it is alphabetic languages as English (Perea & Lupker, 2003, 2004; Perea et al., 2008; Luke, 2011), French (Schoonbaert & Grainger, 2004), Dutch (Van Heuven, et al., 2001), and Spanish (Perea & Lupker, 2004), syllabic languages as Japanese Katakana (Perea & Pérez, 2009), or logographic languages as Chinese (Yang, 2013; Gu, Li & Liversedge, 2015), although the TL and SL primes contain exactly the same number of letters and both are meaningless nonwords.

When using masked priming lexical decision task to tap into TL priming effects, the tricky manipulation is that the precedent TL and SL nonwords are hidden between a series of forward masks (#########) and the target word, which is the word to be recognized (JUDGE). Plus, primes are presented very briefly, around 40-67 milliseconds (Perea & Lupker, 2003). Thus, it is impossible for participants to realize the existence of the primes, and their processing is essentially unconscious and automatic. Nonetheless, studies suggest that readers can still make a more accurate decision on TL nonword primes (jugde) than SL nonword primes (junpe). In this regard, it would indicate that TL nonword primes are very effective at activating the lexical representation of their base words (JUDGE) and the process of orthographic matching tolerates minor changes in letter position.

However, what most previous studies have examined are generally words that are written horizontally from left to right. Recently, psycholinguists have started to consider whether text orientations have an influence on the TL priming effects, addressing questions as: will transposed letter priming effects still exhibit when words are written in unfamiliar orientations, such as from right-to-left horizontally, top-tobottom vertically, bottom-to-up vertically, or rotated by 90° or 180°? When reading an unfamiliar text orientation, will readers demonstrate the same TL priming effects as reading a familiar one? Will bilinguals transfer their first language (L1) text-reading experience to the second language (L2) reading? Considering different visuospatial coordinates and readers’ language backgrounds, theoretically, do people who are accustomed to reading multiple orientations develop separate representations of letter or character position for each orientation, such as one set of representations for horizontal texts and a completely separate set for vertical texts? Or would they just learn one abstract representation independently of its orientation?

Successful reading skills involve the basic use of visuospatial identification processes to optimize processing of letter or character identities and positions. Addressing the questions listed above will inform us about why humans can represent and process words that are not one hundred percent accurate, helping us understand the visual constraints on reading words written in extreme forms and how they impact reading at the first level of orthographic processing in skilled readers. As Grainger (2018) suggested, how to model reading words remains one of the major challenges for reading research. The study of automatic orthographic processing such as the TL and SL priming effects will lead to a better understanding of orthographic recognition mechanisms involved in the word recognition system. Moreover, by means of specifying how automatic and tolerant orthographic recognition is processed in skilled readers, the implication of the findings may possibly lead to the development of better ideas and methods for improving and remediating reading skills in children or people with reading and spelling difficulties or deficits (e.g., dyslexia) (Lété & Fayol, 2013).

The present study will pay close attention to findings from the most recent psycholinguistic research, exploring the question of whether unfamiliar text orientations (e.g., texts presented vertically from top-to bottom, from bottom to top, horizontally from right to left and extremely rotated by 90° or 180°) could influence TL priming effects across readers with different language backgrounds (monolinguals vs. bilinguals), especially whether readers’ familiarity with some text orientation(s) would influence readers’ TL word processing in unfamiliar formats. This is with the aim to account for this complex TL reading skills learned by humans from both psycholinguistic and semiotic views in the hope of shedding light on future research that regards words as symbols as well as reading as a cognitive process.

2. Types of Text Orientations in Different Writing Systems

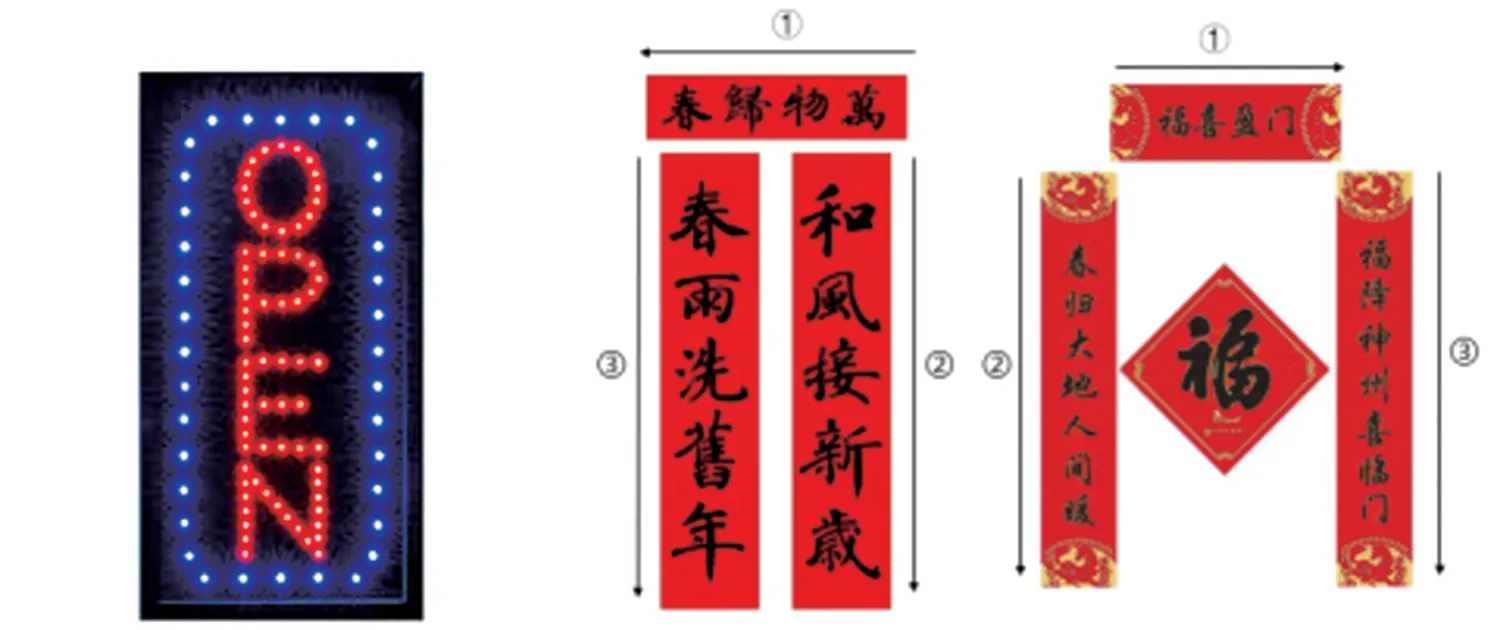

Due to the texture of writing materials (e.g., tortoise shells, stones, bamboo scrolls, paper, etc.), historical reasons or writing habits, text orientation varies with language. Generally, there are two types of text orientations, that is, horizontal writing and vertical writing. Each orientation has two alternative directions; to be specific, depending on what language they belong to, words can flow horizontally from right to left or left to right, and go vertically from top to bottom or bottom to top. For example, words in Indo-European languages are typically written down horizontally from left to right, as in English, Spanish, French, etc. On the contrary, languages such as Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, and Urdu run horizontally from right to left. Moreover, while Mongolian is written from left to right in vertical lines running from top to bottom, many east Asian languages, such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean, can be arranged along either the horizontal or vertical axis, be it horizontally from left to right, horizontally from right to left, or vertically from top to bottom (but with vertical lines proceeding from right to left), with each glyph or character remaining upright by default. Sometimes, both horizontal and vertical texts can even be combined on one page, as Japanese newspapers usually display. In traditional Korean and Vietnamese scripts, both horizontal and vertical writings exist, but they are seldom used in their modern languages. In contrast, English readers have little knowledge of multiple text orientations. Although in some cases, like in advertisements or neon lights, some English words can be written down from top to bottom, for example, the word “OPEN” appearing vertically to save space or attract attention in a marquee fashion (see the first picture in Figure 1), readers from alphabetic languages do have very limited experience in reading different text orientations.

To the best of our knowledge, Chinese is more flexible in text orientations than the other languages. Besides the conventional left-to-right horizontal direction, it can also flow occasionally from right to left in horizontal lines and top to bottom in vertical columns. A typical example is Chinese Spring Festival Couplets, which consists of a horizontal couplet and two vertical couplets. There are two ways to arrange word directions in this type of text. One is the traditional version (see the middle picture in Figure 1) in which text on the horizontal scroll runs from right to left, followed by text on the column couplets written from right to left in vertical lines. The other format is that the horizontal texts run from left to right, and the column texts are read from left to right vertically (See the third picture in Figure 1). By comparison, although Japanese can be legitimately written vertically and commonly written horizontally from left to right, it does not run texts horizontally from right to left.

Figure 1. Examples of English texts presented vertically and two versions of text orientations in Chinese Spring Festival Couplets

3. Empirical Studies on TL Priming Effects with Different Text Orientations and Readers of Different Language Backgrounds

In order to investigate whether text orientations have an impact on the TL priming effects, psycholinguists carried out experiments with participants from different language backgrounds, involving monolinguals such as English (Witzel, Qiao & Forster, 2011; Yang & Lupker, 2019), Chinese (Yang, Chen, et al., 2018; Yang, Hino, et al., 2020), Spanish (Perea, Marcet & Fernández-López, 2018), and Japanese (Witzel, Qiao & Forster, 2011), and bilinguals, such as Japanese-English bilinguals, Chinese-English bilinguals and Arabic-English bilinguals (Witzel, Qiao & Forster, 2011; Yang, Jared, et al., 2019). A central approach to address the question is to use the masked priming lexical decision task.

In a masked priming lexical decision task (Forster & Davis, 1984), following a row of hash masks, a prime (either a TL nonword or a SL nonword) is presented briefly for 50 milliseconds, then participants are required to make a quick YES or NO response to a string of letters or characters (i.e., the target) presented on the computer screen. If one thinks the target word is a real word that exists in that language, one should press the YES button, but if one thinks the target doesn’t exist in that language, one should press the NO button. Reaction times are compared when the same target is preceded by a masked TL prime versus by an SL prime. Because of the brief presentation of the primes, it is impossible for participants to consciously recognize the prime and use strategies to make decisions. Thus, reaction times on the same target will reflect how the TL and SL prime activate the base word.

Although there is substantial literature on TL studies presented horizontally from left to right, the issue of whether varied text orientations have an influence on TL priming and whether readers’ familiarity with certain text orientations influence TL priming effects have just arisen as new research interests in recent years. Nonetheless, the available empirical studies have revealed some surprising findings.

3.1 Empirical findings from readers with experience in reading both horizontal and vertical texts

Both Japanese and Chinese readers have some experience in reading texts presented horizontally and vertically. Japanese readers are equally familiar with texts written from left-to-right horizontally and top-to-bottom vertically. By comparison, Chinese readers are exposed to more types of text orientations because Chinese texts can also be presented right to left horizontally. In line with their reading experience, empirical findings suggest that Japanese and Chinese readers can process TL nonword primes both horizontally and vertically.

In the study of Japanese Katakana words reported by Witzel, Qiao and Forster (2011), native Japanese speakers showed significant TL priming effects in both horizontal and vertical text orientations (see the left picture in Figure 5). What’s more, their performance (i.e., priming effect size) with these two directions were similar and their responses to vertical texts were as fast as to horizontal ones.

Yang, Chen, et al. (2018) investigated the impact of multiple text orientation in four-character Chinese masked TL priming effects, which was referred to as “transposed-character (TC) priming effects” in the Chinese case. The way to create four-character TC and substituted character (SC) nonwords is the same as creating English TL and SL nonwords. For example, a TC nonword prime “有不所同” is based on the real four-character word “有所不同” by transposing the two middle characters, and a SC nonword prime “有扑走同” is created by replacing two middle words. The TC priming effect is the time difference for the same target (有所不同) following a TC nonword prime (有不所同) versus a SC nonword prime (有扑走同). In this study, participants were presented four text orientations, which were as follows: 1) primes and targets both in the conventional left-to-right horizontal orientation, 2) primes and targets both in the vertical top-to-bottom orientation, 3) primes and targets both in the right-to-left horizontal orientation, and 4) primes (right-to-left orientation) and targets (left-to-right orientation) in an opposite orientation (e.g., 同不所有-有所不同). Results revealed that Chinese native speakers demonstrated significant TC priming effects inallfour text orientations, be primes and targets presented horizontally (leftto-right and right-to-left), vertically (top-to-bottom) or even in a contrary fashion (right-to-left vs. left-to-right).

Figure 2. Examples of Chinese texts presented in different text orientations (adapted from Yang, Chen, et al., 2018)

Taken together, Japanese and Chinese readers can show significant TL priming effects in both horizontal and vertical orientations, although the two scripts involved are different, with one being syllabic (Katakana) and the other logographic (Chinese). It should be noted that the size of TL priming effects obtained from the two orientations is equivalent in Japanese, that is, Japanese readers can produce similar TL priming when Japanese texts are presented horizontally and vertically. This may be strong evidence that familiarity with both text orientations affects TL priming effects to the same extent for Japanese readers. However, what’s more surprising is that Chinese readers are even able to produce TC priming effects when the text orientations of primes and targets are opposite, an orientation which would never occur in real-life readings, indicating that Chinese readers’ particular reading experience with both right-to-left and left-to-right text orientations may help them to develop a more flexible orthography coding system.

However, the above evidence is not convincing enough to support that readers’ familiarity with particular text orientations is determinant in TL priming effects. More compelling TL priming evidence should come from participants who have little or no experience in a certain text orientation so that we could know if previous reading experience matters in a novel text orientation.

3.2 Empirical findings from readers with little experience in reading top-tobottom texts

The primary evidence concerning the impact of unusual text orientation on TL priming effects is provided by words presented vertically from English and Spanish scripts, which are written horizontally from left to right by default (Witzel, Qiao & Forster, 2011; Perea, Marcet & Fernández-López, 2018).

One key finding, first reported by Witzel, Qiao and Forster (2011), is that significant masked priming effects can be obtained from English TL nonword primes displayed in a marquee (top-to-bottom) format (see Figure 3). The participants in their experiments were native English speakers who are not familiar with a top-to-bottom writing direction, but they could still respond quickly to activate the TL nonword primes. Their results demonstrate clearly that despite the lack of experience in top-tobottom reading, vertical TL priming in English can still be obtained.

A follow-up study that examined whether vertical TL priming exists in Spanish was reported by Perea et al. (2018). They tested whether Spanish readers who were also accustomed to horizontal reading could rapidly activate the identity and the order of the letters presented in a marquee format. Once more, the result showed that native speakers of Spanish, lacking vertical reading experience as English speakers, could still be able to generate significant TL priming effects and achieve a stable orthographic coding process during word recognition.

Figure 3. Examples of marquee text from Witzel et al. (2011) and Perea et al. (2018)

These two experiments suggest that significant TL priming can be obtained from words displayed in an unfamiliar vertical format, despite English and Spanish readers lack such reading experience. Now, a relevant question is how extreme the text format can be in achieving the TL priming effects.

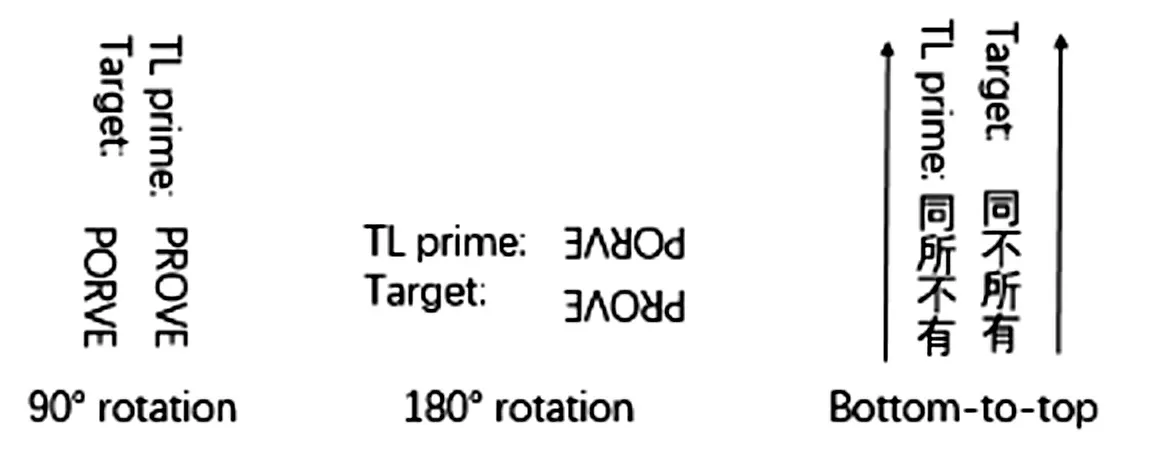

3.3 Empirical findings from texts rotated by 90°, 180° and bottom-to-top vertically

The most crucial question is whether readers could still produce TL priming effects with texts presented in extremely unusual ways. Evidence is provided by experiments tested with English texts rotated by 90° and 180° (upside-down presentation) and with Chinese texts presented vertically from bottom to top, none of which would be presented in real life readings for these participants.

Presenting Spanish texts in a top-to-bottom (upright) format as well as a 90° rotation orientation, Perea, Marcet and Fernández-López (2018) compared the size of TL priming effects in these two unusual vertical orientations. Their results revealed significant masked TL priming effects in both orientations, and the magnitudes of the two directions were found to be equivalent.

By examining the TL priming effects with English monolinguals, Yang and Lupker (2019) replicated this 90° pattern and extended the result to a 180° rotation. Their results also showed that even with the visual input drastically altered to a 180° rotation, the magnitude of the TL priming effects was equivalent across both orientations, and both effects were significant.

Yang, Chen, et al. (2018) examined the TC priming effects of Chinese readers by using a completely unseen orientation that presented from bottom to top. However, Chinese readers still produced surprisingly robust TL priming effects.

Figure 4. Examples of text presented in 90° rotation and 180° rotation (adapted from Yang, Jared, et al., 2019) and vertically from bottom to top (adapted from Yang & Lupker, 2018)

Results from those studies suggest that dramatically altered visuospatial input in a 90° rotation, 180° rotation and bottom-to-top orientation does not disrupt TL or TC priming effects. Even readers who completely lack experience in dealing with drastically rotated visual texts were still able to rapidly activate the identity and the order of the letters. It seems that those rotated primes are as effective at activating word representations as those TL primes presented horizontally.

Empirical findings from the above studies on monolinguals suggest that readers’ processing of TL words is independent of their familiarity with particular text orientations. Participants could produce significant TL priming effects regardless of whether their native languages contain that text orientation or not. If language background does not matter in monolinguals’ production of TL priming effects in their native language, will language backgrounds matter in their L2 TL word recognition? That is to say, will their L1 experience in reading text orientations be transferred to their L2?

3.4 Empirical findings from bilinguals regarding TL priming effects in unfamiliar text orientations

Researchers evaluated the role of the first language experience on the second language word recognition under different text orientations. They examined whether the impact of varied text orientations on TL priming effects in L1 could be extended to an L2, especially when the L2 has fewer text orientations or is a particularly different script from L1. Since English is rarely written down vertically, an ESL (English as a Second Language) bilinguals’ exposure to vertical text in English, their L2, would be extremely limited, just like English native speakers. For example, Japanese-English bilinguals are accustomed to reading horizontal texts as well as vertical texts in Japanese (L1), but as ESL learners, they are only familiar with horizontally organized English (L2) texts. For those bilinguals, will TL priming effects demonstrated in both Japanese text orientations be completely absent in L2 texts? Will they exhibit a vertical TL priming effect even in English (L2)? If bilinguals’ L2 orthographic coding skills are developed from L2 (English), then Japanese-English bilinguals should demonstrate TL priming only in the horizontal direction when reading English words but not in the vertical dimension.

Witzel, Qiao and Forster (2011) examined both the horizontal and vertical English TL priming effects with Japanese-English bilinguals who were proficient in English (see Figure 5). The results demonstrated that Japanese-English bilinguals produced significant masked TL priming effects in both orientations when reading L2 (English) words, and the critical finding was that despite the absence of any extensive experience with vertical English text, those bilinguals did produce vertical TL priming effects in L2, although the size was smaller than with horizontally presented words. However, Witzel, Qiao and Forster’s (2011) findings could not prove that bilinguals’ L2 orthographic coding with an unfamiliar text dimension was transferred from L1 because monolingual English speakers also demonstrated a significant TL priming effects with vertical English words.

Figure 5. Examples of vertically presented Japanese and English text (Perea et al., 2018)

In another study, Yang, Jared, et al. (2019) investigated backward repetition priming effects with Chinese-English and Arabic-English bilinguals in a masked L2 (English) lexical decision task. The primes and targets were the same (repetition) words, but primes were ordered from right-to-left and targets maintained left-to-right. The researchers examined whether bilinguals would produce backward repetition priming effects when reading L2 and compared the bilinguals’ performance with English monolinguals. The results demonstrated that English monolinguals and Arabic-English bilinguals produced null effects, but Chinese-English bilinguals produced significant backward repetition priming effects. As the typical reading habits for Arabians are right to left, but they did not exhibit backward repetition priming, the effects produced by Chinese-English bilinguals could not be attributed to their ability and the experience of reading from right to left.

It can be inferred that the results so far regarding whether bilinguals could transfer their L1 text reading ability to L2 are mixed. However, these results may suggest that Chinese-English bilinguals have a more flexible (i.e., less precise) letter position coding system than Arabic-English bilinguals and English monolinguals.

4. Theoretical Accounts for the Impact of Unfamiliar Text Orientations on TL Priming Effects with Readers from Different Language Backgrounds

Orthographic processing is mainly focused on deriving information about letter identities and letter positions. An investigation of malposition in letters or characters could reveal the underlying cognitive mechanisms that are difficult or impossible to detect by normal word processing; thus, studies of this kind play an important role in language research (Wang, 2014). An important question for understanding the nature of internal orthographic processing is whether unfamiliar text orientation has an influence on the TL priming effects and whether readers’ previous reading experience with particular text orientations affect TL priming effects.

A review from the most recent literature suggests that readers who are familiar with both horizontal and vertical texts, like Japanese and Chinese native speakers (Perea et al., 2018; Yang, Chen, et al., 2018), did demonstrate TL priming effects in both directions in their native languages. Moreover, readers who lack experience in vertical readings, like English and Spanish native speakers (Perea et al., 2018), also produced TL priming effects in a top-to-bottom way when reading English and Spanish respectively. On top of that, readers who have null experience in reading drastically altered texts, for example, texts rotated by 90°, 180° or presented from bottom-to-top as shown in Lupker and colleagues (2018, 2019), demonstrated significant TL priming effects as well. Taken together, although readers came from different language backgrounds such as alphabetic scripts (English and Spanish), syllabic script (Japanese Katakana) or logographic script (Chinese), and no matter whether they were familiar with certain text orientations, they all demonstrated letter position coding skills in great flexibility, which suggests that the influence of text orientation on the TL priming effects is very limited for monolingual speakers and TL priming effects may be obtained independently of text orientation. Even if readers lack reading experience with absolutely novel text orientations, their orthographic coding ability was not affected, either.

The above findings from available literature are inconsistent with the explanations of perceptual learning account (Grainger & Holcomb, 2009) but are consistent with the abstract letter unit account (Witzel, Qiao & Forster, 2011).

According to the perceptual learning account, TL priming effects are dependent on readers’ familiarity with specific text orientations and previous reading experience. This account implies that if readers are familiar with certain text orientation(s), they would produce significant TL priming effects, but if they have little or no experience in a text orientation, no TL priming could be obtained. However, the available evidence so far does not support this account because even if readers lack knowledge of certain text orientations, they could still process inaccurate letter codes successfully in an unfamiliar orientation.

The abstract letter unit account, however, proposes that the orthographic coding process acts at a totally abstract level and activation is coming from the prior activation of a shared set of abstract letter units. When texts are presented in varied visuospatial orientations, readers can quickly convert the letter units from a spatial code (horizontal or vertical) into an abstract representation, which operates rapidly in an ordinal (first-to-last) code and can then be used to activate the base word regardless of the text orientation of the original form. The abstract code account assumes that readers will code the beginning letter/character as the first position, and the next letter/character the second position, and so on. For example, when the nonword prime JUGDE is presented horizontally, it will be coded in an ordinal format as “J is the first position and U is the second position, etc.”, rather than encoded in a spatial format as “J is one letter left of U, and U is one letter right of J, etc.”. When “JUGDE” is presented vertically, J is also coded as the first position and U as the second position, etc., in an ordinal format just as the word is arranged horizontally, instead of being coded spatially as “U is above D”, etc. In extreme circumstances, when readers see texts rotated by 90° or 180°, they will also rapidly scan the text and convert the strange visuospatial code of rotated words into abstract letter units before they make lexical decisions. So, during the word recognition process, no matter how unfamiliar or drastically different the visual input is presented, text orientations do not play a crucial role and TL priming effects can still emerge.

Because the orthographic coding process is ordinal in nature, abstract letter unit accounts predict that readers’ previous text-reading experience plays little role in TL word recognition and it allows the activation of lexical representations even with noncanonical directions, regardless of the familiarity with particular texts. The empirical studies with English, Spanish and Chinese readers who have little or no experience in reading texts presented vertically (Witzel et al., 2011; Perea et al., 2018), rotated by 90° or 180° (Yang & Lupker, 2019), or run from bottom to top (Yang, Chen, et al., 2018) all support this prediction. According to abstract letter unit accounts, readers from these different language backgrounds could rapidly convert an unseen visuospatial code to a stable ordinal (first-to-last) code during word recognition and produce TL priming effects.

So far, research from monolingual experiments suggests that TL priming effects are independent of the presented text orientation and individuals who lack experience in reading texts presented in unusual orientations could still produce TL priming effects. This remarkable ability to process rotated letter strings is a demonstration of the resilience of the word identification system during reading (Perea et al., 2018). Overall, the abstract letter unit account of TL priming is plausible to explain the findings from various TL priming effects under different text rotations for monolinguals.

However, monolinguals are skilled readers and findings from native languages may not apply to a second language. The present bilingual evidence regarding whether TL priming effects can be obtained from various text orientations in L2 is mixed. For example, Japanese-English bilinguals who have extensive experience in reading both horizontal and vertical texts in Japanese (L1) also showed significant vertical TL priming effects in English (L2) (Witzel et al., 2011). Moreover, Chinese-English bilinguals who are occasionally exposed to right-to-left text orientation in Chinese also demonstrated significant L2 (English) backward repetition priming effects, an extreme form of TL priming (Yang, Jared, et al., 2019). The evidence from Japanese-English and Chinese-English bilinguals may suggest that various text-orientation reading experience in L1 may be expanded to L2 TL text reading. In contrast, Arabic-English bilinguals who are good at reading texts arranged from right to left failed to produce backward repetition priming effects. Therefore, it seemed that we could not jump easily to the conclusion that L1 reading experience could be transferred to L2 texts in TL word recognition. Although one may attribute the contradictory bilingual results to script differences in Japanese, Chinese and Arabic, or associate the results with lexical properties such as L2 proficiency, the familiarity with the script, etc., at the very least it may reflect a distinct difference in word recognition between native language and second language regarding the impact of text orientation on TL priming effects.

From a semiotic perspective, Saussure’s conception of the signifier and the signified could offer us a different understanding (Wang, 2014). In Saussure’s account, all signifiers or language symbols are combined with highly abstract sound images and no matter how much they are transformed or deformed, they still refer to the same sound-based images. The signifier is stored in our long-term memory and they are the consequences of conceptualization. For the same signified (e.g., JUDGE), they could have different signifiers. For example, the signified JUDGE is translated as “法官” in Chinese but as “ジャッジ” in Japanese, so both “法官” and “ジャッジ” are the signifiers of JUDGE. Although they appear differently in linguistic forms, they refer to the same signified. Therefore, the signifier can be presented differently, and different fonts, colors, pictures, or even TL words will not render a different representation of the signified. For example, previous studies have found that masked priming effects can be obtained between words that are visually dissimilar, such as uppercase words (e.g., EDGE) and lowercase words (e.g., edge) (Bowers, Vigliocco & Haan, 1998; Perea, Jiménez & Gómez, 2014), between handwritten words and printed words (e.g.,-CABLE) (Gil-López et al., 2011), between words that are visually similar symbols or digits (e.g., M473RI4L-MATERIAL) (Perea, Duñabeitia & Carreiras, 2008), and between CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, e.g.,) and normally printed words (Hannagan et al., 2012). To be specific, Hannagan et al. (2011) used masked priming lexical decision experiments to investigate humans’ ability to read CAPTCHAs, which are word shapes under extreme distortions that people frequently encounter when surfing the Internet in order to tell the computer if the user is a human or a machine. Hannagan et al. (2012) demonstrated that even such extreme cases of shape distortion can’t prevent readers from recognizing them automatically in a brief 50-millisecond duration, without making explicit use of slow inferential and guessing processes. This means that a completely unusual transformation of the signifier is still remarkably efficient to activate the signified and humans have a system for orthographic processing that is highly tolerant to noise and shape variations during the very early stages of visual word recognition in skilled readers (Hannagan et al., 2012).

The same rationale should apply to transposed-letter words or transposedcharacter words under unfamiliar text orientations, which can also be taken as extreme formats of the signified (i.e., the base word). In this sense, even under unusual text orientations, TL or TC words as signifiers are still closely related to the same signified (i.e., the base word) and their recognition can rapidly and efficiently activate the corresponding target. Take the TL nonword JUGDE for example: it contains all the same letters as the target word or the signified (JUDGE), so the letter units activated by the TL nonword prime (JUGDE) can activate the lexical representation for JUGDE more fully and rapidly than a SL nonword prime (JUNPE) which only shares three letters with the target word JUDGE, generating significant TL priming effects even in strange text formats such as rotated by 90° or 180°.

According to Saussure, the basic ideas of the signified and the signifier are mental concepts and they contain highly abstract elements of semantics (Wang, 2014). In this sense, it appears that both the abstract letter unit account in psycholinguistics and Saussure’s account in semiology support that TL word recognition is basically a cognitive process that is abstractly represented and operated.

5. Conclusion

Based on the most recent literature review, this study aimed to answer the question of whether transposed-letter or -character words in unfamiliar text orientations would affect reading with readers from different language backgrounds and, more importantly, to explain the findings from both psycholinguistic and semiotic perspectives. Theoretically, readers should have interference or difficulty in recognizing transposed-letter or -character words in unfamiliar or extremely altered text orientations. However, the available results suggest that although readers have little or no experience in reading unusually orientated words, they could still rapidly convert the unfamiliar visuospatial code into an abstract letter or character, supporting an abstract letter units account for TL priming effects. Meanwhile, the empirical results can also be understood from Saussure’s conception of the signifier and the signified. Therefore, both views support that TL or TC words are abstractly represented and operated in monolinguals’ minds and independent of the text orientations.

However, there are mixed findings in L2 TL priming effects from bilinguals. Therefore, more bilingual researches are needed in the future in order to reveal the complex cognitive mechanism underlying their orthographic system. Also, the present studies mainly concentrate on single word recognition, and future research is suggested to investigate longer text units than words (e.g., sentences) in order to specify how orthographic information can be processed across parallel words.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Nigerian Languages and Identity Crises1

- A Multimodal Critical Study of Selected Political Rally Campaign Discourse of 2011 Elections in Southwestern Nigeria

- Semiotic Resourcefulness in Crisis Risk Communication: The Case of COVID-19 Posters

- A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Saudi Arabic Television Commercials

- The Temporality of Chinese from the Perspective of Semantic Relations

- A Study of Natural Elements in French Ecological Writer Jean Giono’s Works