心搏骤停后接受静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合支持患者的神经系统并发症分析

席绍松 朱英 刁孟元 金光勇 陈嘉伊 胡炜

[摘要] 目的 分析接受静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合支持的心搏骤停患者出现神经系统并发症的流行病学、临床特征和危险因素。 方法 回顾性分析2012年6月~2019年6月期间我科收治的22例因心搏骤停而接受静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合(V-A ECMO)辅助的成年患者(>18岁),分为有神经系统并发癥组及无神经系统并发症组,并对比两组患者基本资料、与CPR和 ECMO相关的资料等数据的差异性。 结果 22例ECPR患者中,63.6%出现神经系统并发症,其中位年龄、接受主动脉内球囊反搏辅助的比例、连续性肾脏替代治疗的比例及ECMO辅助前的中位pH值和血肌酐中位含量均明显高于无神经系统并发症组。有神经系统并发症组患者的自发循环恢复(ROSC)中位时间、持续无搏动灌注超过12 h的比例、ECMO持续时间、深镇静持续时间、ECMO运行24 h的气道内峰压、脓毒症发生比例及28 d病死率等均明显高于无神经系统并发症组(P<0.05)。此外,多因素回归分析发现,年龄、CA到ROSC时间、持续无搏动灌注超过12 h、深镇静持续时间是ECPR患者发生神经系统并发症的独立危险因素。结论 心搏骤停后接受ECPR的患者出现神经系统并发症的发生率高,与不良结局密切相关。年龄、深镇静持续时间、CA到ROSC时间、持续无搏动灌注超过12 h是ECPR患者发生神经系统并发症的独立危险因素。

[关键词] 心搏骤停;体外心肺复苏;神经系统并发症;回顾性研究;静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合

[中图分类号] R54;R65 [文献标识码] A [文章编号] 1673-9701(2020)28-0034-07

Analysis of neurological complications in patients receiving venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after cardiac arrest

XI Shaosong ZHU Ying DIAO Mengyuan JIN Guangyong CHEN Jiayi HU Wei

Department of Critical Care Medicine, the Affiliated Hangzhou First People's Hospital,Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310006, China

[Abstract] Objective To analyze the epidemiology, clinical features, and risk factors of neurological complications in cardiac arrest patients receiving venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Methods A total of 22 adult patients(>18 years old) who received venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation(V-A ECMO) due to cardiac arrest in our department from June 2012 to June 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. They were divided into a group with neurological complications and a group without neurological complications. The differences in basic data, CPR and ECMO-related data, and other data of the two groups were compared. Results Among 22 ECPR patients, 63.6% developed neurological complications. The median age, the proportion of receiving intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, the proportion of continuous renal replacement therapy, and the median pH and the median content of blood creatinine before ECMO was significantly higher than that of the control group. The median time of the return of spontaneous circulation(ROSC), the proportion of continuous non-pulsatile perfusion for more than 12 hours, the duration of ECMO, the duration of deep sedation, the peak airway pressure within 24 hours of ECMO operation, and the incidence rate of sepsis and the 28-day mortality rate in patients with neurological complications were significantly higher than those in the control group(P<0.05). In addition, multivariate regression analysis found that age, the time from cardiac arrest to ROSC, continuous non-beating perfusion for more than 12 hours, and the duration of deep sedation are independent risk factors for neurological complications in ECPR patients. Conclusion Patients who received ECPR after cardiac arrest have a high incidence of neurological complications, which are closely related to adverse outcomes. Age, duration of deep sedation, time from CA to ROSC, and continuous non-pulsatile perfusion for more than 12 hours are independent risk factors for neurological complications in ECPR patients.

[Key words] Cardiac arrest; Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation(ECPR); Nervous system complications; Retrospective study; Venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

心搏驟停(Cardiac arrest,CA)后在心肺复苏期间接受静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合(Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,V-A ECMO)支持,被命名为体外心肺复苏(Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation,ECPR),是得到美国心脏协会[1]和欧洲复苏委员会[2]认可的一种先进的抢救方法,利用体外循环来维持传统CPR难以逆转的循环耗竭[3]。ECPR不仅能维持重要器官的灌注,还可以识别并治疗潜在的心脏骤停的可逆原因。

然而,由于ECPR患者病情的严重程度和长时间的体外循环,容易导致各种并发症,最终对患者的存活产生不利影响[4]。多个关于ECPR的研究已经关注到患者的神经系统并发症[5-6],其表现从轻度的认知障碍,到脑卒中、脑出血、缺血缺氧性脑病、甚至脑死亡等均有表现,原因也是多元化的。本研究旨在回顾性分析在本中心接受ECPR辅助的心搏骤停患者出现神经系统并发症的流行病学、临床特征和危险因素,现报道如下。

1 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料

本研究回顾性分析2012年6月~2019年6月我院重症医学科收治的所有院内和院外心搏骤停后接受V-A ECMO辅助的成年患者(>18岁)。本研究已通过我院医学伦理委员会审查。

1.2 方法

参考现有研究报道[5]并结合本中心工作经验,制订患者纳入标准和排除标准。纳入标准:(1)时间节点:V-A ECMO辅助过程中、V-A ECMO撤离后住院期间、发病28 d内;(2)神经系统并发症的类别:通过格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow coma scale,GCS)<15分(经口气管插管患者GCS<11分)、脑功能分类量表评分(Cerebral performance category score,CPC)>2分、并结合重症监护病房(Intensive care unit,ICU)常用的谵妄评估方法(Confusion assessment method for the ICU,CAM-ICU)、影像学检查,识别出停用镇静药物48 h后仍短期或持续存在的昏迷、认知障碍(包括谵妄、抑郁)、癫痫、缺血缺氧性脑病、缺血性脑卒中、出血性卒中等精神性和器质性病症及死亡等。所有患者的信息已被匿名处理以保护患者隐私。排除标准:(1)入院时存在急性原发颅脑损伤,或既往有神经精神症状者;(2)病历资料不全及失访者;(3)ECMO辅助<24 h者。

1.3 观察指标

(1)基本资料:年龄、性别、基础疾病、CA病因、V-A ECMO辅助前的严重程度评估[包括急性生理、年龄和慢性健康评估(Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation Ⅱ,APACHE Ⅱ评分)、序贯器官衰竭评估(Sequential organ failure assessment,SOFA评分)]、生化指标(血气分析、血生化、凝血功能、血常规等)、其他干预措施(包括连续性肾脏替代治疗、主动脉内球囊反搏、机械通气等);(2)与心肺复苏(Cardiopulmonary resuscitation,CPR)相关的资料:CA发生场所、CA到CPR时间、CA到自主循环恢复(Restoration of spontaneous circulation,ROSC)时间、CA时的心电图、瞳孔对光反射阳性比例;(3)与体外膜肺氧合(Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,ECMO)相关的资料:ECMO置管场所、CA到ECMO开始运行时间、ECMO前ROSC比例、24 h低温治疗的实施比率、整个观察周期血液制品(红细胞和新鲜冰冻血浆)的用量以及实施ECMO辅助前后的血管活性药物评分[Vasoactive inotropic score,VIS=多巴胺剂量μg/(kg·min)+多巴酚丁胺剂量μg/(kg·min)+100×肾上腺素剂量μg/(kg·min)+米力农剂量μg/(kg·min)+10 000×血管加压素剂量unit/(kg·min)+100×去甲肾上腺素剂量μg/(kg·min)]、非搏动灌注持续时间、深镇静(Richmond agitation-sedation scale,RASS=-3~-4分)持续时间以及机械通气参数、其他并发症情况等;(4)研究结局指标:ICU住院时间、总住院时间、28 d病死率。

1.4 统计学方法

采用SPSS 22.0统计学软件进行数据处理。分类变量和连续变量分别以计数(百分比)和中位数[M(P25,P75)]表示结果,并根据数据特点选择非参数秩和检验、χ2检验或Fisher精确检验进行对比研究。采用多因素Logistic回归分析方法对差异有统计学意义的变量进行分析,以明确与神经系统并发症相关的独立危险因素。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 患者基本资料比较

在本研究周期内,共纳入22例符合纳入标准的患者(图1)。主要是因为急性心肌梗死(12%)和急性暴发性心肌炎(10%)而继发心搏骤停。根据以上患者是否出现神经系统并发症分为两组,其中14例患者出现神经系统并发症,包括短暂认知障碍5例(包括短暂昏迷和谵妄),持续昏迷(缺血缺氧性脑病)1例,死亡8例(死因分别为顽固性心源性休克5例、脓毒性休克3例);8例患者无神经系统并发症。有神经系统并发症组患者的年龄中位值[62 (40,68)岁 vs. 29(23,37)岁,P<0.01]、接受IABP辅助的比例(71.4% vs. 25.0%,P=0.035)、CRRT的比例(92.8% vs. 50.0%,P=0.039)以及ECMO辅助前pH值[7.26(7.16,7.32) vs. 7.40(7.27,7.46),P=0.044]和血肌酐含量[128(105.8,181.0) μmol/L vs. 91(72.3,112.3)μmol/L,P=0.024]中位值均明显高于无神经系统并发症组。22例患者整体的28 d病死率为36.4%,而有神经系统并发症组患者的28 d病死率明显高于无神经系统并发症组(P=0.018),见表1。

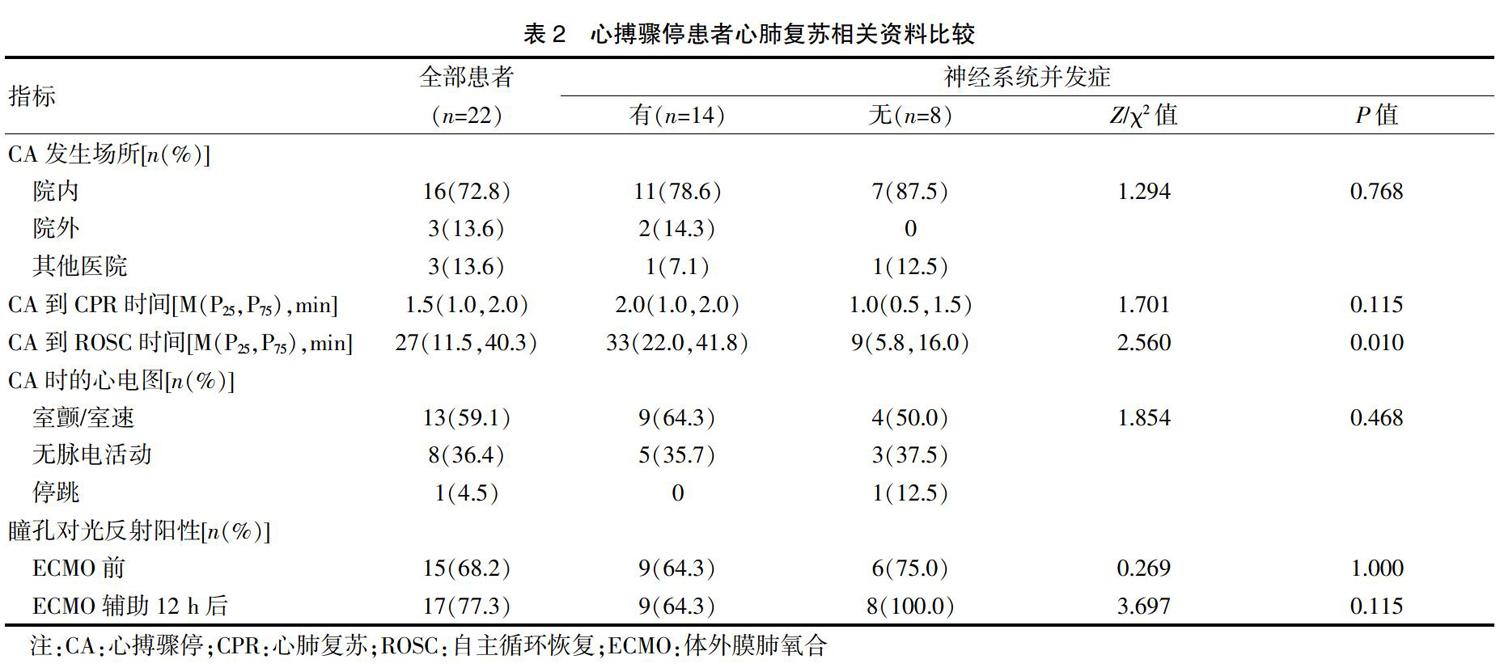

2.2 与患者CPR相关的资料比较

共有16例患者是在院内发生CA,另外有3例发生在院外,3例发生在其他医院,分别经过心肺复苏并成功ROSC后转入本院,所有患者从发生CA到开始实施CPR的中位时间为[1.5(1.0,2.0)] min,从发生CA到成功ROSC的中位时间为[27(11.5,40.3)]min。结果显示,有神经系统并发症组患者的CA到ROSC时间中位数较无神经系统并发症组明显增加[33(22.0,41.8)min vs. 9(5.8,16.0)min,P=0.010]。而两组患者在CA发生场所、CA到开始实施CPR时间以及CA时的心电图类型等方面,差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05),见表2。

2.3 与患者ECMO支持相关的资料比较

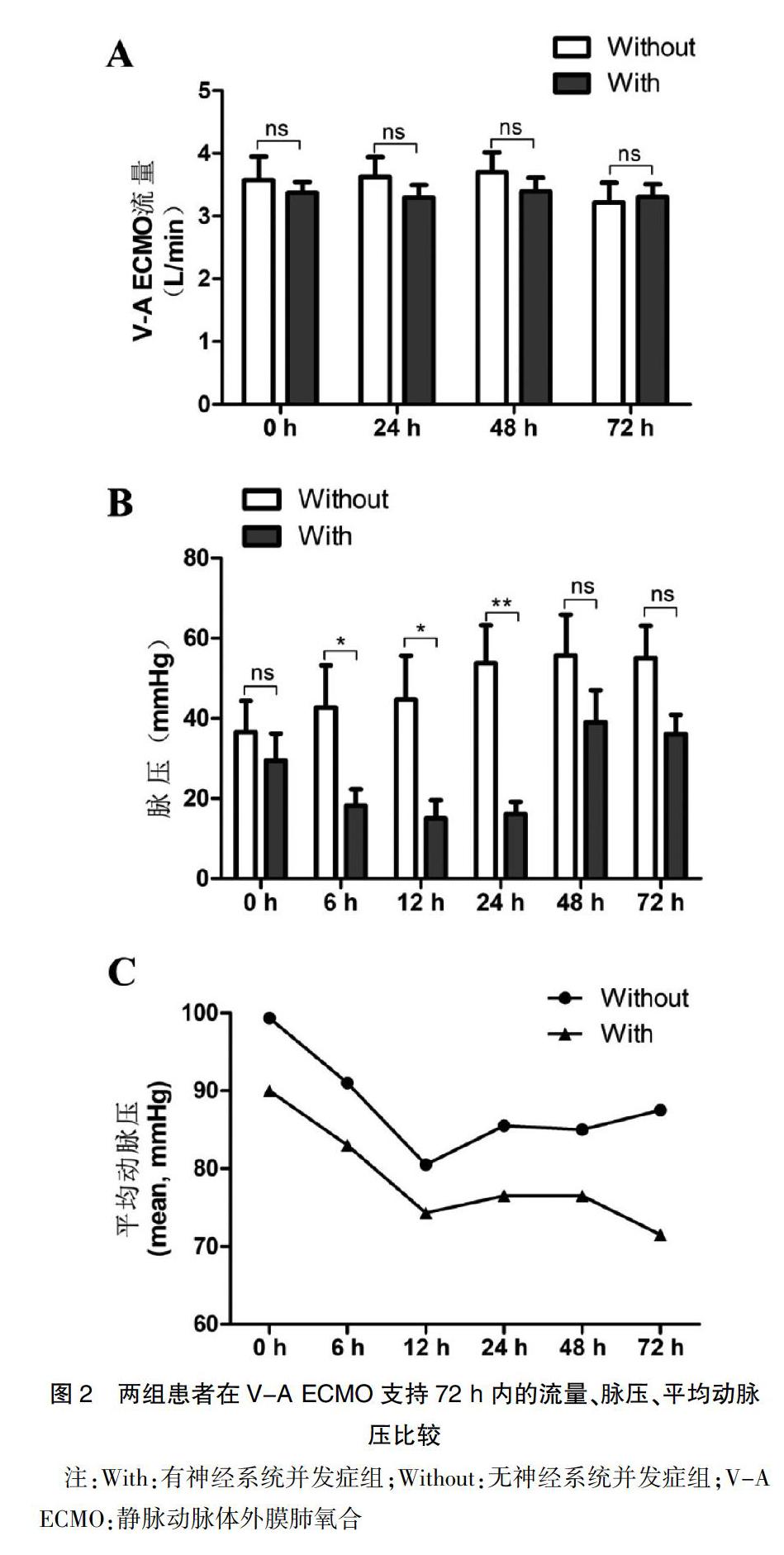

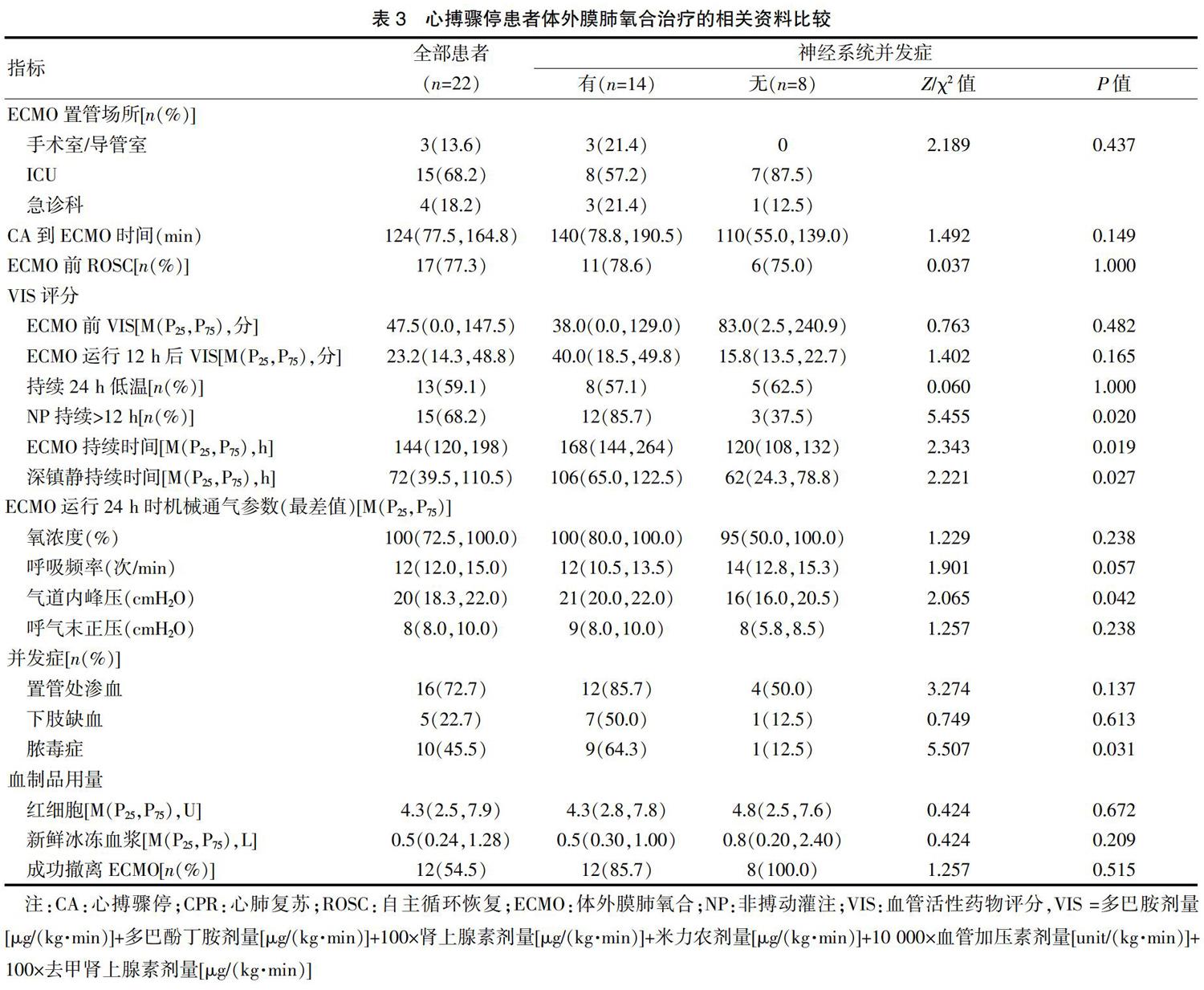

本研究中所有患者均是经过股动脉和股静脉置管实施的V-A ECMO,置管场所分别为手术室(或)导管室3例(13.6%)、ICU 15例(68.2%)、急诊科4例(18.2%),有5例患者在CPR过程中置管运行ECMO并成功ROSC,而17例患者是在ROSC后因顽固性心力衰竭、恶性心律失常而置管接受V-A ECMO支持。有15例患者(68.2%)在接受V-A ECMO辅助后仍有持续超过12 h的非搏动灌注(Non-pulsatile perfusion,NP),或称之为平流状态(脉压,Pulsatile pressure <10 mmHg),其中12例患者出现神经系统并发症,明显高于无神经系统并发症组(85.7% vs. 37.5%,P=0.020),见表3。对两组患者在ECMO支持72 h内的ECMO血泵流速、脉压、平均动脉压(Mean arterial pressure,MAP)进行比较后,结果发现在12 h和24 h,有神经系统并发症组患者的脉压和MAP均明显低于无神经系统并发症组(P<0.05)(图2)。此外,有神经系统并发症组患者的ECMO持续时间、深镇静持续时间、ECMO运行24 h时的气道峰压(Peak inspimtory pressure,PIP)及脓毒症发生比例等方面,均明显高于无神经系统并发症组(P<0.05),见表3。

2.4 ECPR患者出现神经系统并发症的多因素分析

基于上述单因素分析结果,在对CA后接受V-A ECMO支持患者的基线特征、与患者CPR和ECMO支持相关的资料进行调整后进行多因素回归分析,结果显示,年龄(OR per 1-year increment:1.117,95%CI:1.012~1.233,P=0.028)、CA到ROSC时间(OR per 1-min increment:1.062,95%CI:0.994~1.134,P=0.042)、NP持续>12 h(OR:8.917,95%CI:1.260~18.339,P=0.029)、深镇静持续时间(OR per 1-hour increment:1.027,95%CI:0.998~1.056,P=0.046)是ECPR患者发生神经系统并发症的独立危险因素,见表4。

3 讨论

心搏骤停依然是全球第一位的死亡原因[6]。在2019年高级生命支持焦点更新(Advanced cardiac life support focused update)中[7],明确关于体外膜肺氧合技术用于CPR过程的证据和建议。本研究对ECPR的定义是,在心搏骤停后CPR过程中启动的V-A ECMO支持及在ROSC后由于顽固性心力衰竭或恶性心律失常而启动的ECMO支持,均归属为体外心肺复苏(ECPR)。已有研究者关注到对ECPR患者短期和长期神经系统结局的评估,以及年龄对预后的影响[8],并将神经功能预后良好定义为CPC评分为1或2分。本研究中的神经系统并发症既包括远期神经功能结局,还包括体外循环支持过程中及之后28 d内出现的神经系统器质性病变和一过性精神症状。对于短期神经系统并发症,主要依靠GCS评分、CAM-ICU来识别;而远期并发症或结局则参考相关研究[8],定义为CPC>2分。考虑到外出影像学检查的转运风险,未来的研究中有必要增加更多的床旁客观指标有助于便捷的识别神经系统并发症,如颅脑超声、床旁脑电监测等,通过测算脑血流速度和监测脑电活动的变化来及时发现神经系统的器质性病变和精神症状。此外,脑损伤生物标志物(如神经元特异性烯醇化酶,S-100蛋白)也有助于评估心搏骤停后的中枢神经损伤[9-10]。

据体外生命支持组织(Extracorporeal life support organization,ELSO)登記网站公布的1990~2019年期间全球ECMO结局总结,8075例接受ECPR治疗的患者,出院时仍存活的只有2387例(29%)[11]。本研究中,63.6%的患者出现神经系统并发症,其28 d病死率高达57.1%,明显高于无神经系统并发症的患者,而在住院日等短期指标方面无明显差异,提示ECPR继发的神经系统并发症可能更多的影响远期预后,包括长期认知功能障碍和功能残疾等,严重影响患者的生活质量[4]。最近的一项研究证实在CPR持续时间<60 min的患者中,ECPR可以显著提高存活者的神经系统良好结局[12],说明缩短从心搏骤停到ROSC的持续时间能够明显改善患者的神经系统结局。本研究分析与CPR有关的数据后发现,只有发生CA到成功ROSC的持续时间是发生神经系统并发症的独立危险因素。这一方面可能与病例样本量少有关,另一方面可能是因为本研究入组的22例患者中,从发生CA到开始CPR的中位时间仅1.5 min,说明本研究大多数CA患者及时启动CPR。患者CPR的持续时间越长,出现神经系统并发症的风险越高,可能是由于大脑在心搏骤停后、甚至在ROSC后12 h持续存在的低灌注,导致不同程度的缺血缺氧性损伤[13]。本研究中68.2%的心搏骤停患者在接受V-A ECMO支持后仍有持续超过12 h的非搏动灌注期。参考相关研究[14],将V-A ECMO辅助过程中的非搏动灌注定义为脉压(Pulsatile pressure)<10 mmHg。而较高的平均脉压则是V-A ECMO成功撤机和生存的独立预测因素[15-16]。另外,在V-A ECMO用于顽固性心源性休克或心搏骤停中,同时应用主动脉内球囊反搏明显有利于提高生存率和促进V-A ECMO撤机[17],而且在V-A ECMO支持中加入IABP可显著增加有搏动灌注患者的平均脑血流速[14]。以上研究结果显示,在V-A ECMO辅助过程中脑血流降低(灌注不足)和非搏动血流可能在患者出现神经系统并发症的机制中起关键作用。

鎮痛镇静药物的使用也可能会影响对ECPR患者神经系统并发症的准确识别。在ECPR辅助的早期,为了实施低温、降低氧耗等脑保护治疗及保障患者安全和舒适度[18],通常持续输注咪达唑仑联合芬太尼以达到深度镇痛镇静的目标。而咪达唑仑和芬太尼均属于蛋白结合率高的脂溶性药物,体外循环过程中大剂量的使用可能会导致患者在停药后苏醒延迟[19-20],甚至导致患者产生与苯二氮类药物相关的神经精神症状[21],此外,对ELSO登记数据分析后还发现肌酐升高也是ECMO辅助患者神经系统良好结局的重要影响因素[22],这在本研究结果中也有体现,提示ECMO辅助前的肾功能损伤是CA患者出现神经系统并发症的预测因素。

总之,通过回顾性的病例对照研究,得到对临床有一定指导意义的结果,但是仍有一些局限性。首先作为一个单中心回顾性研究,样本量偏少,统计学处理时自由度偏低,可能会对统计分析产生干扰。其次,对神经系统并发症的识别主要是依靠主观评分,今后研究中应增加诸如颅脑超声、床旁脑电监测等客观指标有助于更准确、更及时的识别神经系统的器质性病变和精神症状。因此,未来需要进行严格的随机临床试验或替代性研究设计,最大限度地减少偏差,以阐明ECPR在心脏骤停中的作用。

综上所述,心搏骤停后接受ECPR的患者出现神经系统并发症的发生率高,而且与不良结局密切相关。患者的年龄、深镇静持续时间、CA到ROSC时间、持续无搏动灌注超过12 h等是ECPR患者发生神经系统并发症的独立危险因素。未来有必要进行严格的随机临床试验和分层分析,并增加对ECPR患者远期神经功能预后和认知功能的研究。

[参考文献]

[1] de Caen AR,Berg MD,Chameides L,et al. Part 12:Pediatric advanced life support: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care[J]. Circulation,2015,132(18 Suppl.2):526-542.

[2] Soar J,Nolan JP,B?觟ttiger BW,et al.European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for resuscitation 2015:Section 3. Adult advanced life support[J]. Resuscitation,2015,95:100-147.

[3] Conrad SA,Broman LM,Taccone FS,et al. The extracorporeal life support organization maastricht treaty for nomenclature in extracorporeal life support. A position paper of the extracorporeal life support organization[J].Am J Respir Crit Care Med,2018,198(4):447-451.

[4] Yukawa T,Kashiura M,Sugiyama K, et al. Neurological outcomes and duration from cardiac arrest to the initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest:A retrospective study[J].Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med,2017,25(1):95.

[5] Omar HR,Mirsaeidi M,Shumac J,et al. Incidence and predictors of ischemic cerebrovascular stroke among patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support[J].J Crit Care,2016,32:48-51.

[6] Neumar RW,Shuster M,Callaway CW,et al. Part 1:Executive summary:2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care[J]. Circulation,2015,132:S315-S367.

[7] Panchal AR,Berg KM,Hirsch KG,et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on advanced cardiovascular life support:Use of advanced airways,vasopressors,and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cardiac arrest:An update to the American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care[J]. Circulation,2019, 140(24):e881-e894.

[8] Cesana F,Avalli L,Garatti L,et al. Effects of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation on neurological and cardiac outcome after ischaemic refractory cardiac arrest[J].Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care,2018,7:432-441.

[9] Floerchinger B,Philipp A,Camboni D, et al. NSE serum levels in extracorporeal life support patients-Relevance for neurological outcome?[J]. Resuscitation,2017,121:166-171.

[10] Ruttmann E, Dietl M, Kastenberger T, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with hypothermic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest:Experience from a European trauma center[J]. Resuscitation,2017,120:57-62.

[11] Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry report:International summary[EB/OL]. Available at:https://www.elso.org/Registry/Statistics/InternationalSummary.aspx. January,2020.

[12] Bartos JA,Grunau B,Carlson C,et al. Improved survival with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite progressive metabolic derangement associated with prolonged resuscitation[J]. Circulation,2020,141(11):877-886.

[13] van den Brule JMD,van der Hoeven JG,Hoedemaekers CWE. Cerebral perfusion and cerebral autoregulation after cardiac arrest[J]. Biomed Res Int,2018,2018:4143636.

[14] Yang F,Jia ZS,Xing JL,et al. Effects of intra-aortic balloon pump on cerebral blood flow during peripheral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support[J]. J Transl Med,2014,12:106.

[15] Pappalardo F,Pieri M,Arnaez Corada B,et al. Timing and strategy for weaning from venoarterial ECMO are complex issues[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth,2015,29(4):906-911.

[16] Park BW,Seo DC,Moon IK,et al. Pulse pressure as a prognostic marker in patients receiving extracorporeal life support[J]. Resuscitation,2013,84(10):1404-1408.

[17] Vallabhajosyula S,O'Horo JC,Antharam P,et al. Concomitant intra-aortic balloon pump use in cardiogenic shock requiring veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Interv,2018,11(9):e006930.

[18] SRLF Trial Group. Impact of over sedation prevention in ventilated critically ill patients:A randomized trial-the AWARE study[J]. Ann Intensive Care,2018,8(1):93.

[19] Harthan AA,Buckley KW,Heger ML,et al. Medication adsorption into contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenator circuits[J]. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther,2014, 19:288-295.

[20] Cheng V, Abdul-Aziz MH, Roberts JA, et al. Overcoming barriers to optimal drug dosing during ECMO in critically ill adult patients[J]. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol,2019,15(2):103-112.

[21] Zaal IJ,Devlin JW,Hazelbag M,et al. Benzodiazepine-associated delirium in critically ill adults[J]. Intensive Care Med,2015,41(12):2130-2137.

[22] Lorusso R,Barili F,Mauro MD,et al. In-hospital neurologic complications in adult patients undergoing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation:Results from the extracorporeal life support organization registry[J]. Crit Care Med,2016,44(10):e964-e972.

(收稿日期:2020-05-25)