Factors associated with refractory pain in emergency patients admitted to emergency general surgery

William Gilliam, Jackson F. Barr, Brandon Bruns, Brandon Cave, Jordan Mitchell, Tina Nguyen, Jamie Palmer, Mark Rose, Safura Tanveer, Chris Yum, Quincy K. Tran

1 Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore 21218, USA

2 Research Associate Program in Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore 21201, USA

3 R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore 21201, USA

4 Department of Surgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore 21201, USA

5 Louisiana State University, Louisiana 70803, USA

6 University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore 21201, USA

7 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore 21201, USA

Corresponding Author: Quincy K. Tran, Email: qtran@som.umaryland.edu

KEYWORDS: Serum lactate; Refractory pain; Emergency general surgery; Emergency department

INTRODUCTION

Inadequate pain management of patients in the emergency departments (EDs) is common.[1]Previous studies indicated that 74% of ED patients were discharged with moderate to severe pain,[2]while 57% of patients did not achieve adequate pain management.[3]Since 2012, effective pain management in the ED has become an important aspect of patient care as oligoanalgesia is the major source of patients’ dissatisfaction,[4,5]which also affects financial reimbursement for EDs.[6]

Oligoanalgesia in the ED had been associated with concerns for drug-seeking behavior[1]and providers’perception that pain was exacerbated.[7]A previous study also reported that emergency providers (EPs) did not provide adequate pain medication, even in patients with objective f indings requiring surgical evaluation.[8]However,Tran et al’s study[8]was limited by a small sample size and a heterogeneous group of surgical pathologies(neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, vascular emergencies,etc.). Furthermore, Tran et al’s study[8]showed that increased doses of opioids did not adequately reduce pain among surgical patients presenting with severe pain.

We hypothesized that there are other factors, besides the amount of pain medication, that might be associated with oligoanalgesia in ED patients with surgical pathologies and moderate to severe pain. Our study aims to identify clinical and laboratory factors, in addition to providers’ interventions in EDs, that are associated with refractory pain among a group of patients who are admitted to an emergency general surgery (EGS) for evaluation and management.

METHODS

Patient selection

We performed a retrospective study of adult patients who were admitted to any inpatient unit under the care of EGS service at an academic tertiary center for surgical evaluation and management. We included patients who were admitted to EGS as the primary admitting service between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016. The study was approved by our institution review board.

As a quaternary referral center, ED patients are usually transferred to our hospital from regional hospitals and accepted under EGS service to evaluate the need for emergent surgery.[9]The EGS service at our institution was established to expedite the management of time sensitive general surgical conditions.[10]On any day, the EGS team at our institution is composed of an EGS attending physician, a general surgery fellow physician who is doing a fellowship in EGS, and junior general surgery residents. When patients are accepted to EGS service, the EGS team will evaluate the patients and decide on an overall management plan. The junior surgical residents then manage patients’ minute-tominute pre-operative and post-operative courses. If the patients are admitted to the intensive care unit, the junior surgical residents then coordinate the care plan between the EGS team and the intensive care providers.

We f irst obtained the list of patients from ExpressCare,the department that manages transfers from other hospitals to our institution. Patients were then matched to our electronic medical record system to obtain further clinical information. Patients were included if their triage pain levels were moderate or severe, which was defined as triage pain score 4-6 for moderate and 7-10 for severe pain. Pain levels were recorded by the numeric rating scale(NRS) 0-10.[11,12]We excluded patients: (1) who were not accompanied by sufficient records from referring EDs;(2) who refused pain medication; (3) who were intubated;(4) whose records were missing pain assessments at triage or departure; (5) who were not transferred directly from an ED; (6) who had triage pain 0-3. We also excluded patients who presented first to our ED to avoid selection bias. According to our institutional practice, when patients are admitted to EGS service and boarding in our ED,they are managed by a resident of the EGS team and not emergency medicine providers. ED nurses will contact EGS residents directly for orders and questions. Thus,most of these patients’ management may not reflect the management of ED providers. Furthermore, these patients would have early EGS consultation and intervention, thus having different outcomes compared with other transferred patients.[13]

Outcome

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients who had pain reduction <2 units on the NRS scale between ED triage and departure. Pain reduction ≥2 units was considered satisfactory by ED patients in previous studies.[11,12]Patients whose pain reduction <2 units on the NRS were considered having refractory pain.

Data collection

Investigators were first trained by the principal investigator for data extractions. Data were extracted to a standardized Microsoft Access form (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington DC, USA), and 10%were randomly reviewed by another investigator(WG) to maintain interrater agreement of at least 90%.Furthermore, to reduce bias, investigators, who were blinded to study hypothesis, extracted data in sections,such that investigators responsible for pain data were not aware of EPs’ therapeutic interventions or laboratory values. The team met every other month to adjudicate data disagreements until data collection was completed.

We extracted our independent variables from referring EDs’ records of eligible patients. Extracted data included demographic factors (age, gender, weight,past medical history, and ED diagnoses), triage, and departure pain scores. We also collected ED laboratory components for the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment(SOFA) scores: creatinine, platelet level, total bilirubin in addition to serum white blood cell (WBC) counts and lactate level. If a laboratory value was missing from ED record, we substituted it with the admission value upon arrival at our academic medical center. If a value was missing both at ED and admission at the inpatient unit, we imputed the value as 1. We also extracted ED pharmacotherapeutic interventions such as the total amount of pain medication, the volume of intravenous(IV) crystalloids, names of antibiotics, and anti-emetics administered. We only extracted interventions that were documented, either by ED nursing staff, transport teams,or accepting units’ nurses, as administered to the patients during their stay in the EDs prior to transfer.

To evaluate opioid doses, we converted different oral(PO) or IV opioids to morphine equivalent unit (MEU)as previously described.[14]We considered 5 mg of PO oxycodone, hydrocodone as 2 MEUs, while 0.15 mg of IV hydromorphone or 0.01 mg of IV fentanyl was equivalent to 1 MEU.

Data analysis

We first used descriptive data to describe the characteristics of patients with satisfactory pain reduction or refractory pain. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range as appropriate. These continuous data were compared using the Student’st-test or the Mann-WhitneyU-test when appropriate. Categorical data were compared by the Chi-square test with Yates’ correction.

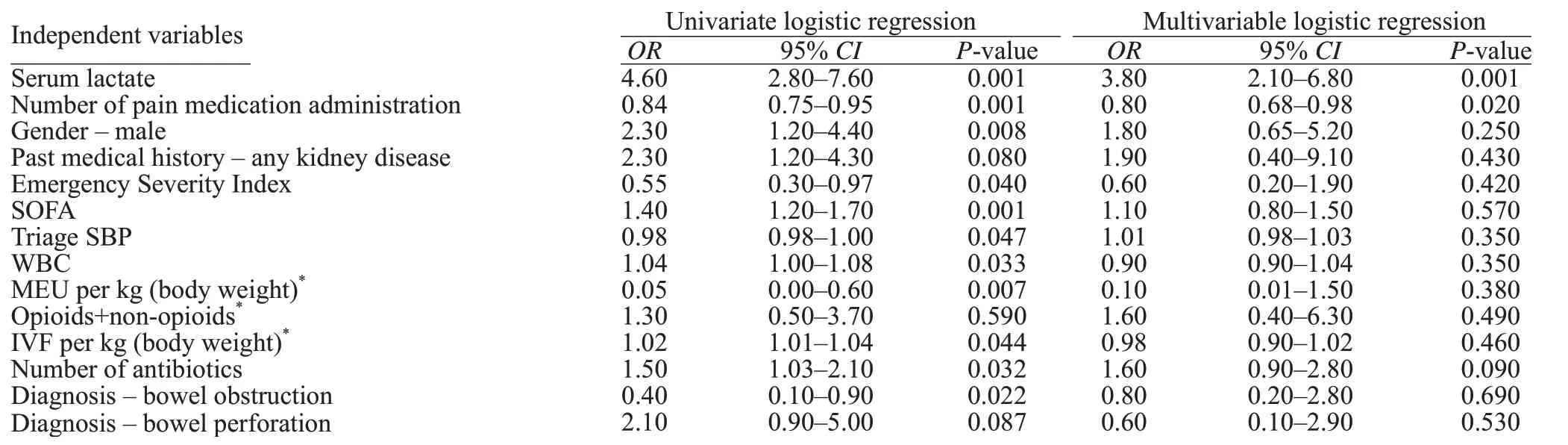

We performed multivariable logistic regressions to assess effects of independent variables on refractory pain.To identify relevant factors for our multivariable logistic regression, we evaluated each independent variable by univariate logistic regressions. We subsequently included only variables with good association with refractory pain(P-value ≤0.10) in the multivariable logistic regression, in addition to a priori-determined clinically significant factors(MEU per kg of body weight; opioid+non-opioid; IV fluid per kg of body weight). Goodness-of-fit of our regression was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test withP-value>0.05 being considered a good f it. We performed statistical analyses using Minitab version 18 (Limited Liability Company, State College, Pennsylvania, USA). All two-tailedP-values <0.05 were considered statistically signif icant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

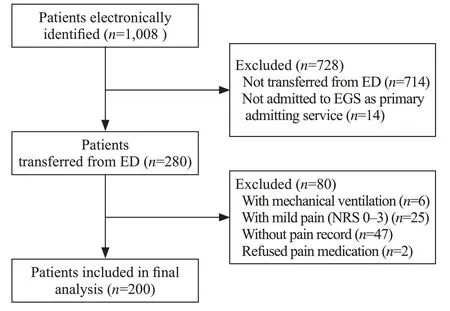

We analyzed the charts of 200 patients who were transferred from different EDs to the EGS service at our academic tertiary center (Figure 1). There were 142 (71%) patients with no refractory pain and 58(29%) patients with refractory pain. The majority of patients were transferred from EDs for evaluation and management of bowel obstruction (20%, 40/200) and bowel perforation (15%, 30/200). While 35% (70/200)of patients did not undergo any surgical operation, 31%(61/200) of patients underwent laparotomy, and 13%(26/200) of patients had laparoscopic surgery during their hospitalization (Table 1).

Figure 1. Patient selection diagram. ED: emergency department; EGS:emergency general surgery; NRS: numerating rate scale.

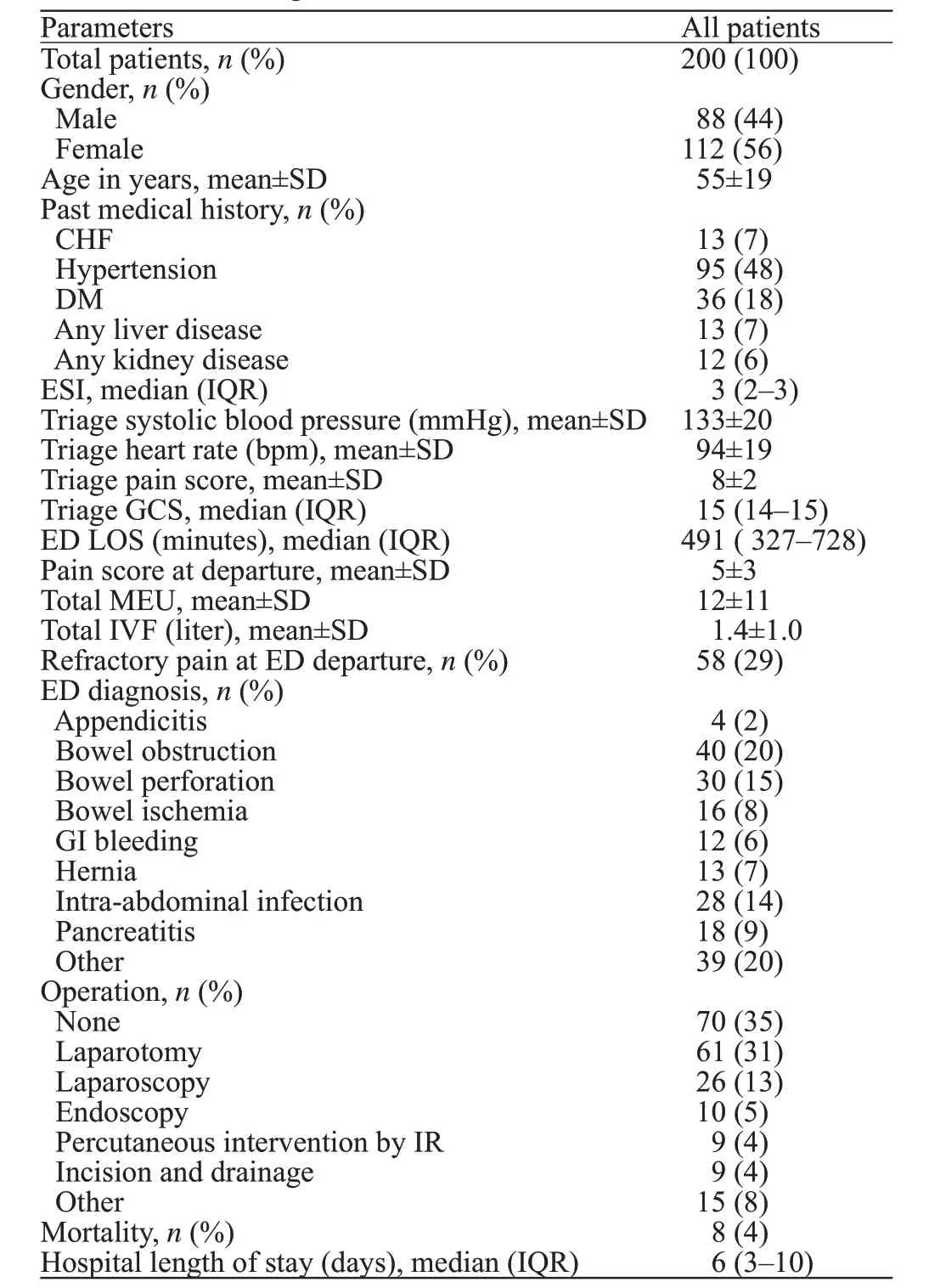

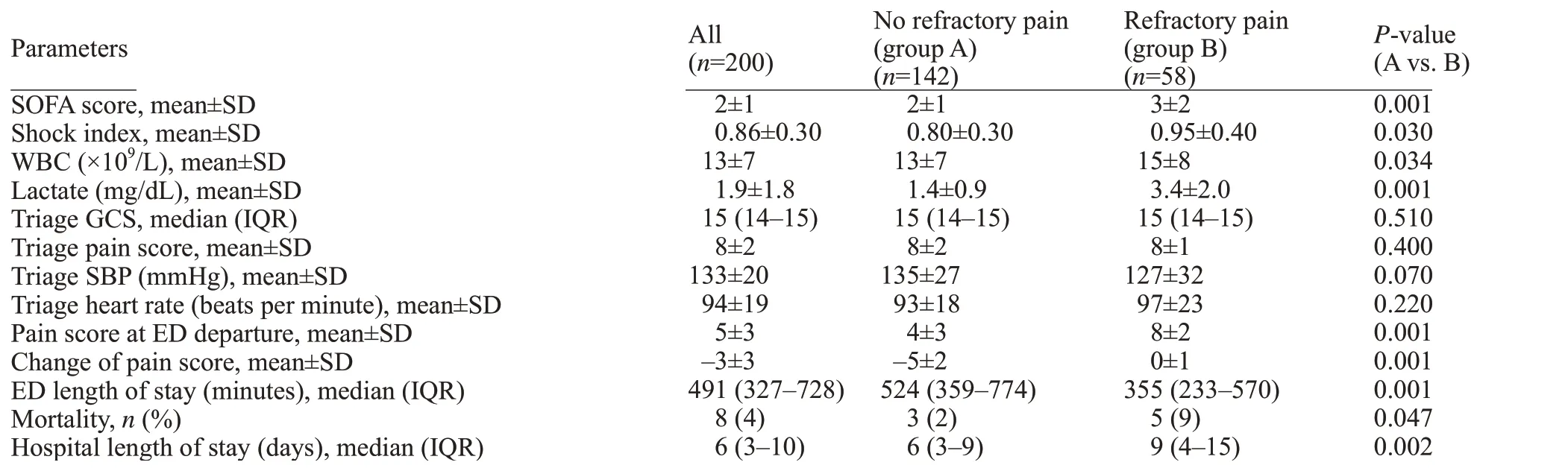

Patients’ clinical factors

Overall, patients with refractory pain had signif icantly higher SOFA score compared with those with no refractory pain. Patients with refractory pain also had significantly higher serum levels of WBC and lactate. Patients with refractory pain had higher pain score at ED departure and a lower rate of pain score change, as compared with patients with no refractory pain. Patients with refractory pain at ED departure also had higher mortality and longer hospital length of stay, as compared with patients with no refractory pain (Table 2).

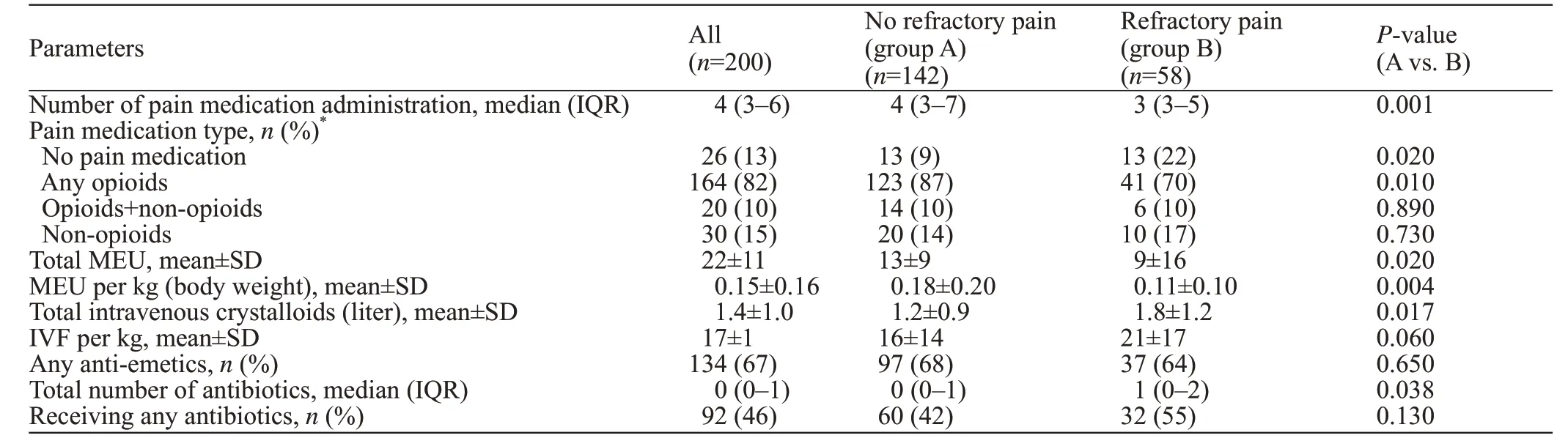

Interventions in the EDs

Patients with refractory pain received less frequent pain medication administration (3 [3-5]) than patients with no refractory pain (4 [3-7],P=0.001) (Table 3).There were also a higher percentage of patients with refractory pain who did not receive any pain medication when compared with those with no refractory pain (Table 3). Furthermore, patients with refractory pain received less MEU per kg of body weight, when compared with patients with no refractory pain (Table 3).

Clinical factors associated with refractory pain at ED departure

Multivariable logistic regression, which only included relevant clinical factors as determined by univariate logistic regression, showed that each mg/dL increment of serum lactate was associated with 3.8 times higher odds that EGS patients had refractory pain when they left the referring EDs (Table 4). Furthermore, each pain medication administration in the ED was also associated with 20% less likelihood that patients had refractory pain at ED departure (odds ratio [OR] 0.80, 95% confidence interval [95%CI]0.68-0.98,P=0.02).

Table 1. Characteristics of ED patients who were admitted to EGS for evaluation and management

DISCUSSION

Our study of patients with moderate to severe pain and transferred to an EGS service for further management showed that almost 30% of patients had refractory pain. Furthermore, only serum lactate and the total number of pain medication administrations were identified as two clinical factors that were significantly associated with refractory pain at ED departure.

Oligoanalgesia in the ED settings has been described in previous studies.[2,3]There had been multiple studies suggesting the underlying causes of ED oligoanalgesia. Miner et al[7]reported that up to 32% of physicians perceived that African American patients exaggerated their pain symptoms by greater than 15 mm on a visual analog scale of 100 mm. Furthermore,providers also hesitated to provide pain medication for concerns of drug-seeking, especially during the current opioid crisis. Providers tended to mistrust patients who reported severe pain in condition related to IV drug abuse[1](soft tissue infection), which was shown to have high percentages of oligoanalgesia, compared with other pathologies.[8]Furthermore, ED providers tended not to give pain medication to patients with possible surgical abdomen until patients were evaluated by surgeons.[15]Similar to previous studies which suggested providerrelated reasons for oligoanalgesia in ED,[1,2,7,15]our study showed that a provider-related intervention (the number of pain medication administration) was associated with refractory pain. However, our study was able to provide an objective cause (serum lactate level) that may have been associated with refractory in ED patients with surgical pathologies. The findings of our study, if confirmed by further studies, will provide an objective measurement for ED providers to assess patients with refractory pain from surgical pathologies.

The mechanism that hyperlactatemia was associated with pain in patients has been unclear. Increased serum lactate level is caused by tissue hypoxia resulting in anaerobic glycolysis[16]and inf lammatory responses.[17]In animal studies, weak acids such as lactic acid activated acid-sensing ion channels responsible for nociception and increased pain.[17-19]It was probable that EGS patients, who had refractory pain in our study, developed hyperlactatemia because of their systemic inf lammatory responses, as evidenced by their higher shock index and SOFA score. Increased serum lactate levels additionally caused higher, longer-lasting pain due to activated nociception receptors. Further studies are needed to confirm our observation and to investigate whether lactate clearance also improves pain in patients with objective f indings responsible for pain as in EGS patients.

A previous study reported that emergency providers did not adequately treat patients who were transferred for surgical evaluations[8]as patients were given a median of 0.09 mg/kg MEU, which was less than the recommended dose of 0.10 mg/kg of MEU.[20]However,our study showed that emergency providers adequately treated these patients who were transferred to an EGS service for further management. Patients with refractory pain in our study received the recommended dose of 0.10 mg/kg of MEU, although this 0.10 mg/kg could also be inadequate[20]in patients with severe pain.Furthermore, patients with refractory pain had shorter ED length of stay, which may have been associated with a lower frequency of pain medication administration.As a result, it was likely that refractory pain in patients with surgical pathologies for EGS as in our study, was caused by patient’s disease severity, which resulted in hyperlactatemia and faster transfer to higher level care, but not from emergency providers’ inadequate interventions.

Table 2. Comparison of clinical factors between patients with and without refractory pain

Table 3. Comparison of ED interventions for patients with and without refractory pain

Table 4. Results from multivariable logistic regression to assess clinical factors and refractory pain among patients admitted to emergency general surgery from emergency departments

Limitations

Our study has many limitations. First, the exclusion of patients who presented first to our institution ED may limit our study’s generalizability as our patient population only consisted of patients who were transferred from other hospitals’ EDs. We could not assess serum lactate clearance as a marker for refractory pain. Almost all patients did not have a repeat lactate level in the EDs, and many patients whose lactate levels were less than 2.0 mg/dL did not have a repeat lactate level upon admission at our quaternary academic center.Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we could not explain the practice variation between emergency providers’ clinical care for these patients. We also did not use mortality and hospital length of stay between patients with refractory pain and with no refractory pain as outcomes in any regression analyses because patient’s mortality and length of stay depended on multiple inhospital factors, besides ED management. Most of these factors would not be available to emergency providers,and would not affect their management of patients prior to transfer.

CONCLUSIONS

Among ED patients with objective surgical pathologies and moderate or severe pain, serum lactate levels were associated with an increased likelihood of refractory pain, despite adequate pain control by emergency providers. Future studies involving pain control in patients with elevated serum lactate are needed.

Funding:The authors received no financial support for the investigation and the development of this manuscript.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by our institution review board.

Conflicts of interest:The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributors:WG, BB, QKT: concept and study design; WG,JFB, BC, JM, TN, JP, MR, ST: data acquisition, data quality,and analysis. All authors participated in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2021年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2021年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Trends and challenges of emergency and acute care in Chinese mainland: 2005-2017

- Identifying critically ill patients at risk of death from coronavirus disease

- Clinical correlates of hypotension in patients with acute organophosphorus poisoning

- Effects of viral infection and microbial diversity on patients with sepsis: A retrospective study based on metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- Effects of metabolic syndrome on onset age and long-term outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome

- Predictors of recurrent angina in patients with no need for secondary revascularization