Safety and feasibility of modified duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy during pancreatoduodenectomy:A retrospective cohort study

Yi Sun, Xiao-Feng Yu, Han Yao, Shi Xu, Yu-Qiao Ma, Chen Chai

Abstract

Key Words: Pancreaticojejunostomy; Pancreatoduodenectomy; Suture technique; Pancreatic fistula

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is widely performed as the standard treatment for resectable tumors in the pancreas and periampullary region. Despite recent advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, the incidence of postoperative complications and overall mortality remain high[1]. Specifically, a postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), the most common and potentially deadly postoperative complication, develops in 5% to 26% of patients[2]. To improve the operation efficacy, effective prevention of POPF can be crucial. Therefore, proper assessment of relevant risk factors for POPF is necessary, and anastomosis has proven to be an effective treatment approach[3]. The intention of this retrospective, single-center study is to explore the risk factors for POPF and further determine the effects of modified duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) on POPF prevention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The data of a series of 215 consecutive patients who underwent elective PD for benign or malignant pathologies in our center between January 2017 and February 2022 were analyzed. Patients were then stratified into two groups according to the anastomotic method for further analysis. Patients with a pathological diagnosis of periampullary lesions, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists score I-III, and who provided informed consent were included in the study. Patients with incomplete medical records, who underwent neoadjuvant treatment preoperatively, who had undergone emergency surgery, or with synchronous cancer were excluded from the study. The primary outcome measure was the POPF rate, and the secondary outcome measures were mortality rates, operative time, blood loss and length of hospital stay. Other outcomes of interest included demographic characteristics (age, sex, anamnesis, concomitant disease, biochemical indices) and intraoperative data (main pancreatic duct (MPD) diameter, pancreas texture, type of anastomosis). According to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery 2016 consensus statement, POPD was strictly defined as “any measurable volume of drained fluid on or after postoperative Day 3 with an amylase level more than 3 times the upper limit of the normal amylase range and having an impact on clinical outcome”[4]. A grade A pancreatic fistula was defined as a "biochemical leak", a grade B fistula required changes in postoperative management, and a grade C fistula needed reoperation or led to organ failure and/or mortality[4]. Mortality specifically referred to the death of inpatients within 3 mo after surgery.

Surgical procedure

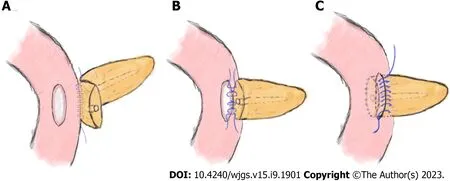

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of end-to-side invagination pancreaticojejunostomy. A: Continuous suturing was performed between the rear side of the pancreatic stump (approximately 1.5 cm from its edge) and the jejunal seromuscular layer with a 3-0 Prolene slip line; B: Suture of the pancreatic margin and seromuscular layer of the jejunum intermittently; C: The pancreatic stump was inserted into the jejunum, and the anterior side of the pancreas and jejunal seromuscular layer were continuously sutured.

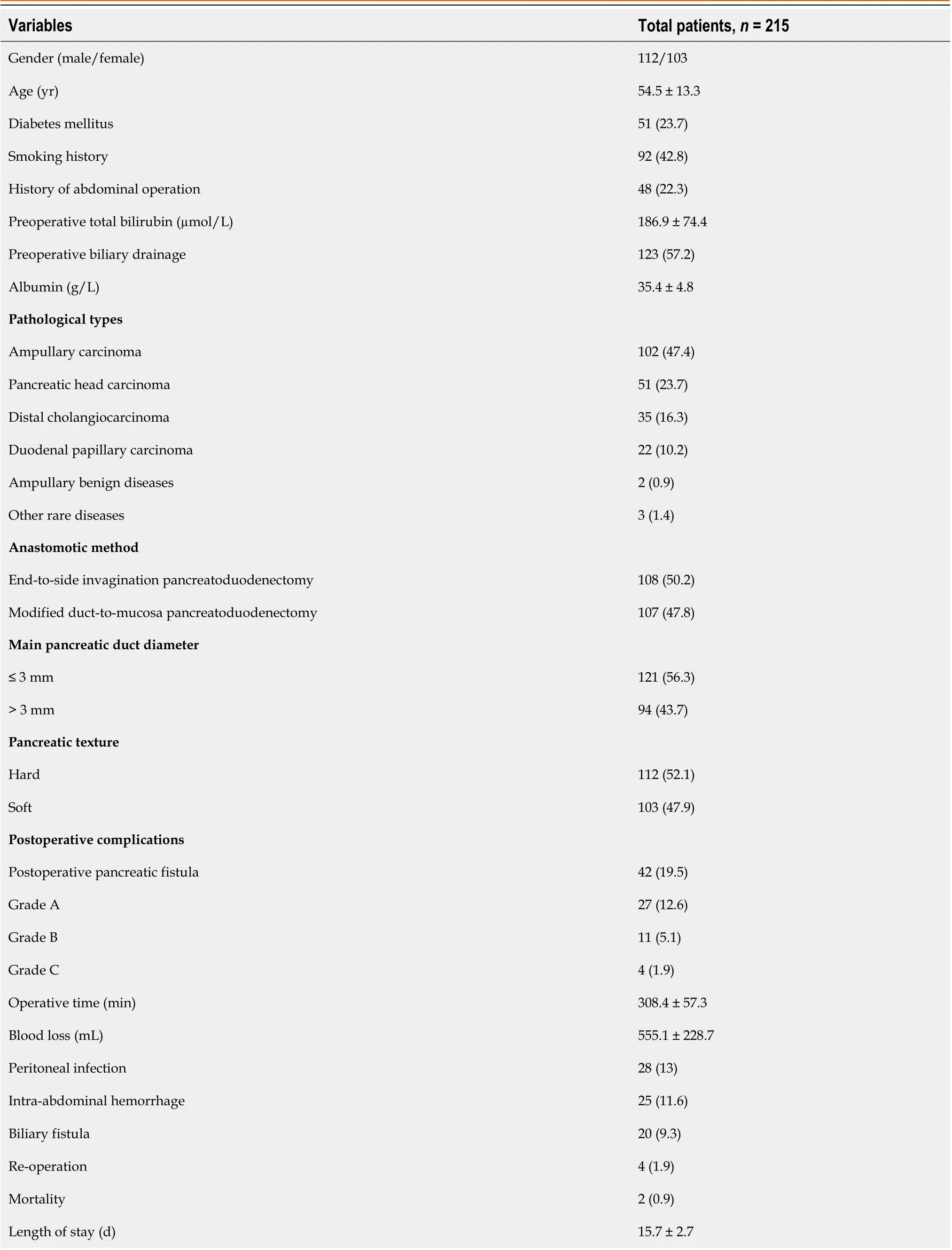

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of modified duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy. A: Perform continuous suturing between the rear edge of the pancreatic stump and jejunal seromuscular layer with a 3-0 Prolene suture; B: Sew 3-4 stiches continuously in the posterior wall of the pancreatic duct and the jejunal mucosa with 4-0 Prolene sutures; C: Continuous suturing was performed between the front edge of the pancreatic stump and the whole layer of the jejunum.

Experienced hepato-bilio-pancreatic surgeons performed standard PD (Child's procedure) on all the patients, and there were no differences between the two groups except for the PJ procedure. The routine procedures for placing the pancreatic stent tube were as follows: After suturing the posterior wall of the pancreatic stump, a right-sized stent tube (8-10 cm in length) with side holes was inserted 3-5 cm into the pancreatic duct, and the other end was placed approximately 5 cm into the small intestine. Then, a stitch was placed to suture and fix the stent tube on the posterior side of the pancreas. Classic end-to-side invagination PJ was implemented as previously reported[5], and the key steps are shown in Figure 1. The procedures of modified duct-to-mucosa PJ were as follows: (1) After enterotomy was performed according to the MPD diameter, the rear edge of the pancreatic stump and the posterior jejunal seromuscular layer were continuously sutured with 3-0 Prolene sutures. The needle was inserted vertically into the pancreas 1.5 cm from the rear edge of the pancreatic stump and passed through the posterior wall of the jejunum after passing through its seromuscular layers. The spacing was approximately 8–10 mm, and the margin was greater than 10 mm (Figure 2A); (2) The posterior wall of the pancreatic duct and the jejunal mucosa were continuously sutured with three to four 4-0 Prolene sutures. The spacing and margin were adjusted according to the MPD diameter (Figure 2B); and (3) After the stent was inserted, the front edges of the pancreatic stump and whole-layer of the jejunum were anastomosed with 3-0 Prolene running sutures. The spacing and margin were similar to those of the first stitch. Although the depth of needle entry was controlled at approximately 1 cm to avoid damaging the MPD on the pancreatic side, it was deeper on the jejunal side to ensure suturing of the whole layer (Figure 2C). In our modified method, tension-free sutures were applied, and no dead space was left between the pancreatic stump and jejunum.

Perioperative management

During the perioperative period, most treatment measures were the same for each patient. The preoperative management included smoking and drinking cessation, weight control, skin preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis. Epidural analgesia and gastrointestinal decompression were administered during the operation. Drain amylase levels were routinely measured on the 1st, 3rdand 5thdays after surgery, while octreotide was used simultaneously for 7-10 d. Other postoperative management included thromboprophylaxis, nutritional support and controlled fluid infusion. The patients were followed up for 3 mo after discharge.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 21.0 statistical software was used for data description and analysis. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD, and Student’s t test was used for comparisons where appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed by using Fisher’s exact test and theχ2test. Univariate analysis was used to evaluate the factors associated with POPF development, and multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors.

RESULTS

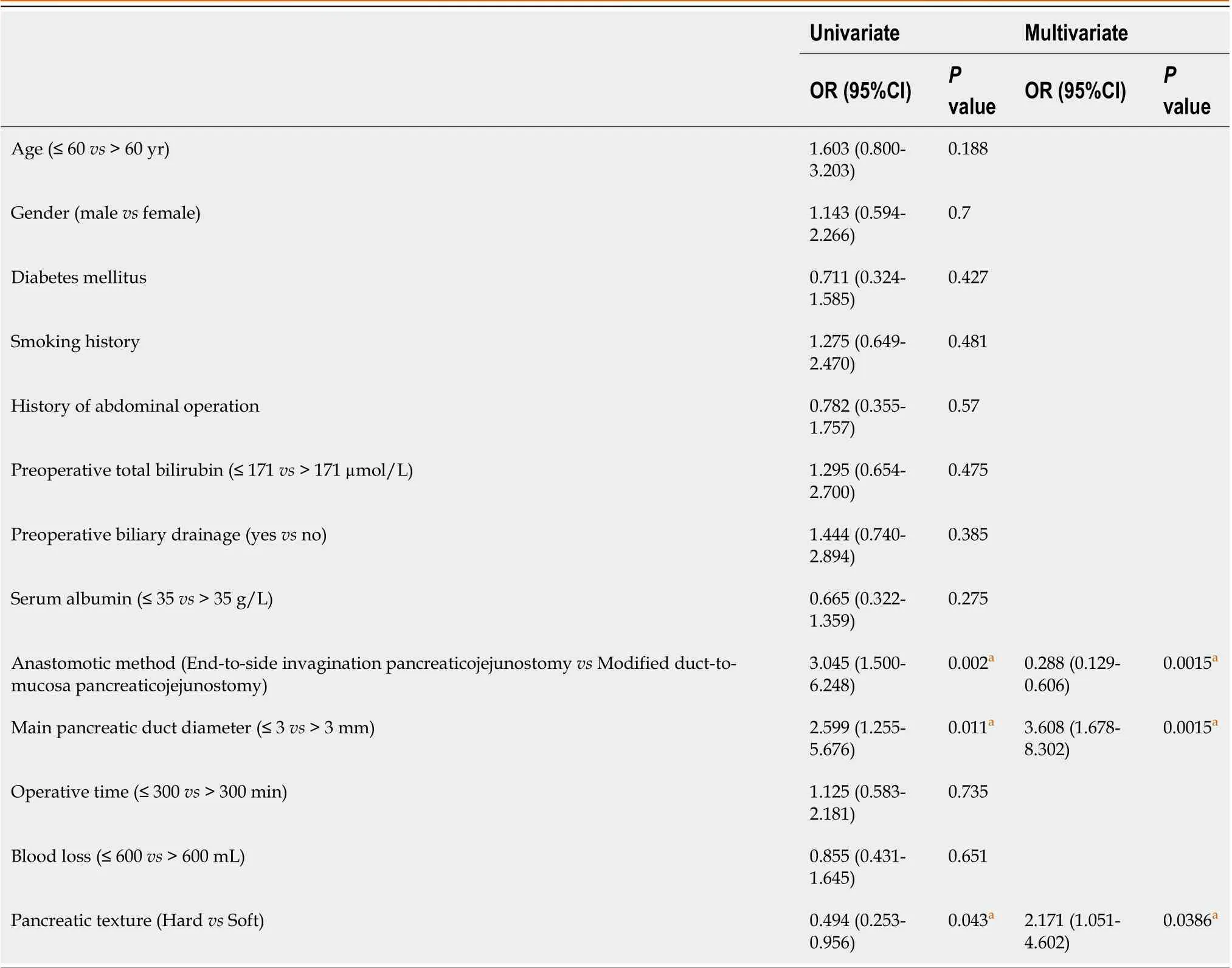

Of the 215 patients with an average age of 54.5±13.3 years, 112 patients were male and 103 were female. The percentages of patients with diabetes mellitus, smoking history and previous abdominal surgery were 23.7%, 42.8% and 22.3%, respectively. Preoperative blood tests showed that the respective values of total bilirubin and albumin were 186.9 (µmol/L) and 35.4 (g/L). More than half of the patients (57.2%) had undergone biliary drainage preoperatively. According to the pathological results, the most prevalent conditions were ampullary carcinoma, pancreatic head carcinoma and distal cholangiocarcinoma. The average total operative time was 308.4 min, while the average intraoperative blood loss was 555.1 mL. The overall complication rate was 53.5% (115/215), and the mortality rate was 0.9% (2/215). Specifically, POPF was the most common complication (19.5%), followed by peritoneal infection (13%), abdominal bleeding (11.6%) and bile leakage (9.3%). Additionally, the two cases of death were due to abdominal bleeding associated with POPF development (Table 1).

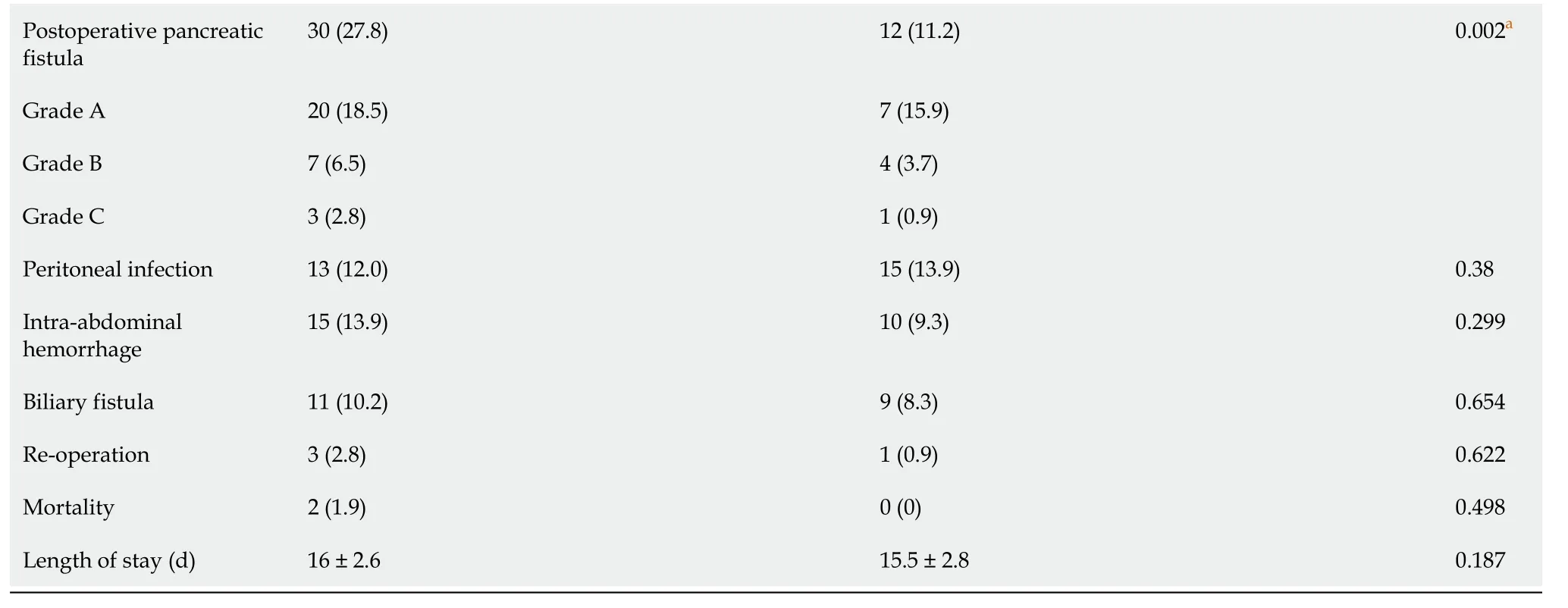

As the most common postoperative complication, POPF can also increase the risks of abdominal infection and hemorrhage[6]. Consequently, we further explored possible factors correlated with POPF development through univariate analysis. As shown in Table 2, POPF development had no significant correlation with the following factors: Age, sex, smoking history, preoperative bilirubin and albumin, preoperative biliary drainage, previous abdominal surgery, blood loss, or operative time. Anastomotic techniques (P= 0.0015), MPD diameter (P= 0.0015) and pancreatic texture (P= 0.0386) were significantly correlated with POPF development in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Table 3 shows the differences between traditional end-to-side invagination PJ and modified duct-to-mucosa PJ. Of these patients, 108 received traditional end-to-side invagination PJ, and 107 received modified duct-to-mucosa PJ. The results indicated no difference between the groups in terms of age, sex, pancreatic texture, postoperative hospital stay or mortality. However, patients subjected to modified duct-to-mucosa PJ had a lower incidence of POPF (11.2%) than the other group (27.8%). Further analysis indicated that there were 7 cases of grade A POPFs, 4 cases of grade B POPFs, and 1 case of grade C POPF in the modified PJ group. However, in the traditional group, the number of cases at each grade was 20, 7 and 3, respectively. Obviously, modified PJ might attenuate POPF severity based on the comparison results. Similarly, the modified anastomotic method demonstrated its superiority in terms of operative time (end-to-side invagination PJ: modified duct-to-mucosa PJ: 333.2 min vs. 283.4 min). Contrary to expectations, there were more patients with MPD diameters less than 3 mm in the modified method group, a factor that was previously found to be significantly correlated with POPF development.

DISCUSSION

With the advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative care, the mortality of patients subjected to PD has gradually decreased, while the incidence of POPF remains high[7,8]. As the most frequent lethal complication, POPF has been heavily discussed to reach a consensus on its prevention. Our research preliminarily found that the independent risk factors for POPF included PJ method, MPD diameter and pancreatic texture. Our result was partially consistent with the result of a recent meta-analysis evaluating pancreatic texture and MPD size as risk factors for POPF development[9]. Other factors, including sex, body mass index, anastomotic techniques, intraoperative blood loss, operative time and drain fluid amylase, have also been reported to be related to POPF development[10-12]. Obviously, numerous studies on the risk factors for POPF have indicated seemingly conflicting and perplexing results. Eckeret al[13] believed that attempting to create a reliable prediction model based on the risk factors for POPF development seemed to be unrealistic and had limited effectiveness. Nevertheless, we believe that the abovementioned factors are valuable references that can help surgeons improve the therapeutic efficacy during the perioperative period.

In clinical practice, various surgical techniques have been applied to prevent POPF development, such as reconstruction methods [PJ, pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)], anastomotic techniques (Blumgart’s method[14], Kakita’s method[15], Peng’s binding PJ[16] and end-to-side invagination anastomosis) and stent placement. Debates about the pros and cons of the various surgical techniques are ongoing. A multicenter randomized trial conducted between June 2009 and August 2012 showed that PG was more efficient than PJ in reducing the incidence of POPF development[17]. Conversely, in another single-center, phase 3, randomized clinical trial, researchers recommended PJ for patients at high risk for POPF development[18]. In the present study, all the patients were subjected to PJ because surgeons were more skilled and experienced in performing this surgical technique. Two PJ anastomotic techniques were used here: end-toside invagination anastomosis and modified duct-to-mucosa anastomosis. The operation time (283.4 minutes) and POPF (11.2%) incidence of the modified method group were significantly lower than those of the comparison group. Our results were roughly consistent with some other surgical center reports[19,20]. Classic invagination PJ can completely drain pancreatic juice from the main pancreatic duct and pancreatic stump into the intestinal cavity, but there are risks of pancreatic stump hemorrhage, pancreatic duct obstruction, and pancreatitis[16,21]. Many scholars have conducted comparative studies of various anastomosis methods. Wanget al[22] found no significant differences among duct-tomucosa PJ, invagination PJ and binding PJ in the prevention of postoperative complications and death. While Ratnayake’s research favored duct-to-mucosa PG[23], Peng’s and Berger’s studies indicated that invagination could reduce the incidence of POPF development more significantly[16,21]. Compared with traditional duct-to-mucosa PJ, our technique used double-layer continuous suturing of posterior tissues and single-layer continuous suturing of anterior tissues, namely, “semicontact continuous anastomosis”. Our modified method had several advantages: first, the procedure better ensured the continuity between the pancreatic duct and the jejunal mucosa; second, tension-free and continuous anastomosis prevented cutting of the pancreas parenchyma; and third, convenient procedures helped reduce the difficulty of PD and the surgeon’s training time. With the popularity of laparoscopic and robotic PD, the advantages of our modified anastomotic approach might better meet the strict requirements of these operations. Although more highquality evidence is required to demonstrate the benefits of modified duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, our present study indicated that it was a feasible and effective method for reducing the incidence of POPF development.

1.2 换药时间安排 两组患者治疗及换药方法相同,对照组清创缝合术后2~3 d首次换药;观察组清创缝合术后第1天首次换药。

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the patients, n (%)

Table 2 Univariate and Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors associated with postoperative pancreatic fistula

aStatistically significant.

This study also has some limitations that might weaken the persuasiveness of the evidence. First, our study is a singlecenter retrospective study with a limited sample size. Second, the limited follow-up time may not accurately reflect the patient’s long-term clinical outcome. Therefore, large-scale randomized studies with long-term follow-up are desperately needed.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found that anastomotic approaches, MPD diameter and pancreatic texture were major risk factors for POPF development. In addition, modified duct-to-mucosa PJ had advantages of shorter operation time and lower POPF incidence over classic end-to-side invagination PJ. Although the findings need to be further validated with more highquality evidence, this modified method could be considered for some patients undergoing PD.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research conclusions

Modified duct-to-mucosa PJ had advantages of shorter operation time and lower POPF incidence over classic end-to-side invagination PJ. Additionally, we found that anastomotic approaches, MPD diameter and pancreatic texture were major risk factors for POPF development.

Research perspectives

Modified duct-to-mucosa PJ is effective and safe according to preliminary outcomes. It is an innovative anastomotic technique with great application prospects in PD and also has broad application prospects in future robotic or minimally invasive operations of pancreatic tumors.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Sun Y and Chai C contributed to conceptualization; Yao H and Yu XF contributed to investigation; Ma YQ and Xu S contributed to data curation; Sun Y contributed to writing – original draft preparation; Sun Y and Chai C contributed to writing – review & editing; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supported byClinical Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation of Jiangsu University, No. JLY2021118; Science and Technology Project of Suzhou City, No. SKJY2021039.

Institutional review board statement:This retrospective study conformed with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The People’s hospital of Suzhou New District.

Informed consent statement:Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the Authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Data sharing statement:The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the Statement- checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Yi Sun 0000-0002-4336-2947; Chen Chai 0000-0002-0258-5650.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Cai YX

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年9期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年9期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Preoperative and postoperative complications as risk factors for delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: A single-center retrospective study

- Comparative detection of syndecan-2 methylation in preoperative and postoperative stool DNA in patients with colorectal cancer

- Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using ultrasound features including elasticity

- Surgical management of gallstone ileus after one anastomosis gastric bypass: A case report

- Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion syndrome and its effect on the cardiovascular system: The role of treprostinil, a synthetic prostacyclin analog

- Advances and challenges of gastrostomy insertion in children