Characteristics of aggressive behavior among male inpatients with schizophrenia

Xiaomin ZHU, Wen LI, Xiaoping WANG*

•Original research article•

Characteristics of aggressive behavior among male inpatients with schizophrenia

Xiaomin ZHU1,3,#, Wen LI1,2,#, Xiaoping WANG1,*

aggressive behavior; schizophrenia; inpatients; psychosocial characteristics; case-control study

1. Introduction

Aggressive behavior in patients with psychological disorders has always been an important issue in clinical psychiatric work because of the high incidence rate and adverse consequences.[1,2]Understanding factors related to aggressive behaviors in inpatients with mental disorders could aid in the evaluation, prevention,and early intervention in those cases where risk of aggressive behavior is high. There is a higher incidence of aggressive behaviors in those patients who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia[3,4,5]and in addition, being male has been shown to be a risk factor for aggressive behavior in patients with mental disorders.[1,2,6,7]Within this context, the current study seeks to better understand psychosocial and clinical factors related to aggressive behavior in hospitalized male patients with schizophrenia. The national mental health law of China provides for the involuntary hospitalization of those individuals with severe mental illness when there a high risk (or actual behaviors) of harm to self or others.Therefore, in addition to the tools measuring aggressive behaviors and tendencies, we also used this legal definition into account when considering the concept of“aggression”.

2. Participants and Methods

2.1 Study participants

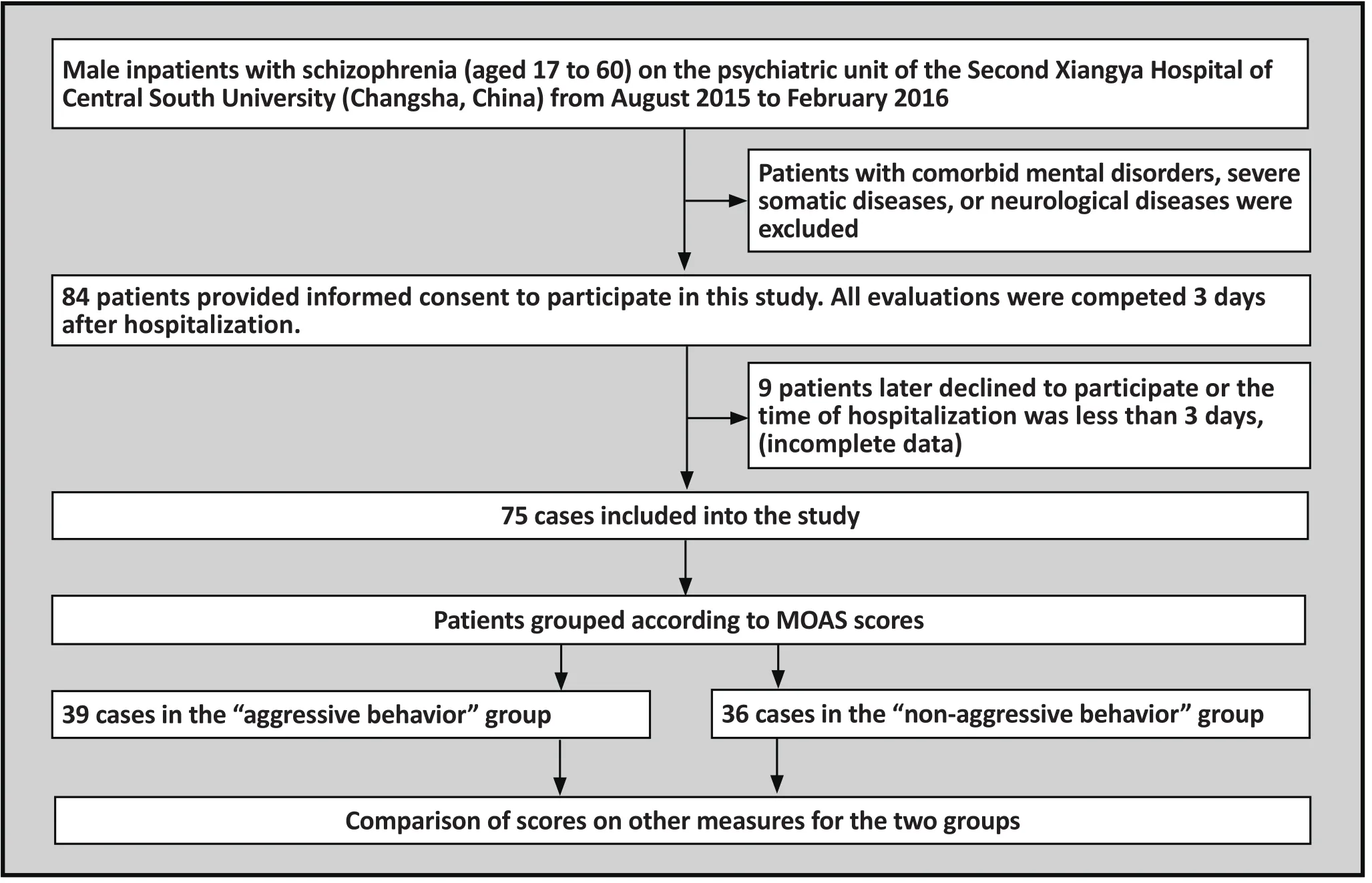

Figure 1 shows the recruitment of study participants.This study used a continuous sampling method to select male inpatients with schizophrenia admitted to the psychiatric unit of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Changsha, China) from August 2015 to February 2016. The inclusion criteria were the following: (a) meeting the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia according to the tenth edition of the international classification of diseases (ICD-10);(b) aged 17 to 60; (c) had normal intelligence, able to communicate with the researchers; (d) informed consent was obtained from patients and their families.The exclusion criteria were the following: a) comorbidity with other mental disorders; b) comorbidity with severe somatic diseases or neurological diseases.

There were a total of 84 cases collected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study and their family members, and this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital.After removing 9 incomplete cases the final number of cases was 75 (a participation rate of 89%). These 75 cases were divided into the “aggressive behavior” group(36 cases) and the “non-aggressive behavior” group(39 cases) according to their scores on each item of the modif i ed overt aggression scales (MOAS). In the MOAS,a score of 0 on each of the items, a score of 0 in the total weighted score, or having a score of 1 or more on the ‘verbal threat’ section of the test were classif i ed as being in the “non-aggressive behavior” group. Those participants receiving a score of 1 or more on test section related to aggression against possessions, self or others were considered as part of the “aggressive behavior” group.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study

2.2 Measurement tools

2.3.1 Self-administered general information questionnaire

a) Demographic information was collected including the following: age, marital status, education level, history of illness, frequency of past hospitalizations frequency;b) In addition, additional information about the family environment was collected including: early unhealthy family environment, family history of crime, situations involving alcohol or other substance abuse by parents,etc.

2.3.2 Historical clinical risk management-20 (HCR-20)

The HCR-20 contains 20 items: historical factors (10 items), clinical manifestations (5 items), and future risk management (5 items). These 3 aspects involve a comprehensive assessment on the risk of violence in patients with mental disorders. Numerous studies,in both China and elsewhere, demonstrate that the HCR-20 has good reliability and validity.[8,9,10]This study took the scores in each item of HCR-20 as evaluation indicators (excluding H6 severe mental disorders and H7 mental illness). For each item on the scale there are three possible choices “not present”, “possibly present”and “definitely present”, represented as 0, 1, and 2,respectively.

2.3.3 Psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R)

The PCL-R is a scale used to evaluate mental illness as part of the HCR-20 evaluation. PCL-R has been revised by researchers in China, and its reliability and validity have been verif i ed.[11]This scale includes 20 items. Each section had a choice of ‘none’, ‘possible or not serious’,and ‘definite’ (i.e 3 selections, scored as 0, 1, and 2,respectively). The scale is divided into four factors including interpersonal factors, emotional factors,lifestyle factors, and antisocial factors, with items 11 and 17 not counted on any factor.[12]Each factor score is the total score of the items contained in that section.In this study, we used the factor scores on the scale as evaluation indexes.

2.3.4 Modif i ed Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS)

MOAS is a widely used assessment tool for violent behavior. Xie introduced the MOAS into China and tested the consistency of its raters.[13]MOAS assesses frequency and intensity of aggressive behavior of individuals with mental disorders over the past week.The scale has 4 parts: verbal aggression, aggression against objects, aggression against oneself, and physical aggression against others. Each part of the scale is divided into five levels according to the severity of the aggressive behavior, (e.g. score of 0 equals ‘no aggression’ whereas a score of 4 equals the ‘maximum’level of aggression). In this study, the MOAS scores were used as the basis for whether or not the participant was classif i ed as being in the “aggressive-behavior” group.

2.3.5 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) is an assessment tool that is used to assess the presence of psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and the severity of each symptom. PANSS is comprised of the positive symptom scale (7 items), negative symptom scale (7 items), general psychopathology scale, and supplemental items (3 items), in total 33 items. These 33 items can also be divided into groups according to the symptoms: (a) lack of response, (b) disturbed thinking,(c) activation syndrome, (d) paranoia, (e) depression,and (f) aggression. This study mainly used the scale score and the symptom score as assessment indicators.Each item on the scale ranges from 1 to 7 based on the frequency and severity of the symptom. The scores for the scale and symptoms were the total score of all included items in those sections.

2.3 Data Entry and Analysis

Data collection was completed by one researcher. All evaluations were completed within 3 days after the participant was hospitalized. Data for the history scale of the HCR-20 and the evaluation period measured by the MOAS and PANSS were the recent week before patients’hospitalization. The scope of the remaining evaluations was any point during the patient’s life. Sources of evaluation data included patients, the patients’ family members, interviews with the presiding doctor and patients’ medical records.

2.4 Statistical analysis

SPSS version 19.0 statistical software was used to perform data analysis. The socio-demographic information and each assessment tool’s total score and the factor score were described statistically using the mean, standard deviation, constituent ratio, and frequency. t-test, chi-square test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used to test for statistical differences in sociodemographic information and each assessment tool’s total score and factor score between the “aggressive behavior” and “non-aggressive behavior” groups. Any factors of significant difference were put into logistic regression to conf i rm major risk factors after the use of univariate analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Comparison of general demographic data and unhealthy family environment factors between the aggressive and non-aggressive groups

As shown in table 1, there was no statistical difference between the groups in socio-demographic factors such as age, history of illness, marital status, and educational level. There was no significant difference in any item asking about unhealthy family environment factors between the two groups.

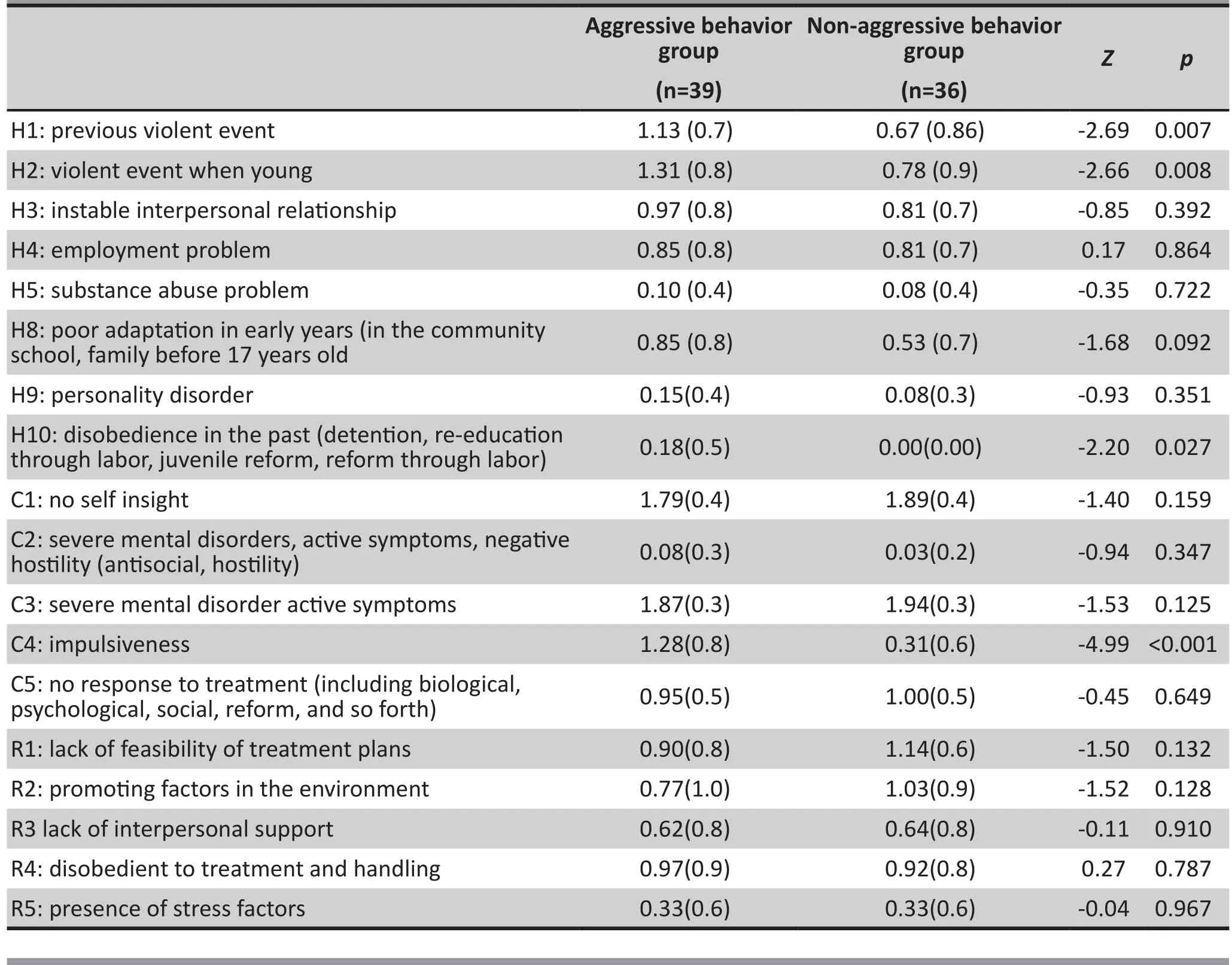

3.2 Comparison of the HCR-20 scores between the“aggressive behavior” and “non-aggressive behavior” groups

As shown in table 2, the items that had a significantly higher score in the “aggressive behavior” group than the “non-aggressive behavior” group were:H1 (previous violent event) (mean(sd)=1.13(0.70) v.0.67(0.76), Z=-2.69, p=0.007), H2 (violent event during childhood) (mean(sd)=1.31 (0.77) v. 0.78 (0.87), Z=-2.66,p=0.008), H10 (history of oppositional or antisocial behavior resulting in: incarceration, admittance to a labor reform program or juvenile reform program(mean(sd)=1.18 (0.51) v. 0.00 (0.00), Z =-2.20, p=0.027),C4 (impulsiveness) (mean(sd)=1.28 (0.79) v. 0.31 (0.58),Z=-4.99, p<0.001). There were significant differences between the two groups in the other items of this measure.

3.3 Comparison of the PCL-R scores between the“aggressive behavior” and “non-aggressive behavior” groups

As shown in table 3, the factor with the highest score (as well as being statistically significant) was the antisocial factor (mean(sd)=1.46 (1.47) v. 0.53 (0.94), Z=-3.40,p=0.001). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in the other factors on this measure.

3.4 Comparison of the PANSS scores between the“aggressive behavior” and “non-aggressive behavior” groups

As shown in table 4, the factors with higher (as well as significantly different) scores in the “aggressive behavior” group were the following: activationsyndrome (mean(sd)=4.90 (2.22) v. 4.08 (1.75)Z=-2.00,p=0.045), paranoia(mean(sd)=8.00(3.28) v. 6.53(2.89),t=-3.05, p=0.043), depression (mean(sd)=7.62(3.78) v.4.08(1.75), Z=-2.49, p=0.013). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in other factors on this measure.

Table 1. Comparison of socio-demographic and family environment data between the 2 groups

Table 2. Comparison of mean (sd) HCR-20 total scores and factor scores between the 2 groups (mean [sd])

Table 3. Comparison of the PCL-R total scores and the factor scores between the 2 groups (mean [sd])

3.5 Stepwise regression analysis

Factors found to be significantly different between the two groups were further divided into psychosocial factors and clinical factors. The psychosocial factors included H1 (previous violent events), H2 (violent event during childhood), H10 (history of oppositional or antisocial behavior resulting in: incarceration,admittance to a labor reform program or juvenile reform program), and the antisocial factor on the PCL-R. Clinical factors included C4 (impulsiveness) on the HCR-20 and activation syndrome, paranoia, and depression on the PANSS. The stepwise logistic regression analysis (the p-values for entering the equation and exclusion were 0.05 and 0.01) was performed using “whether or not the participant was in the aggressive behavior group” as the dependent variable and the 4 psychosocial factors mentioned as the covariant. The final factor entered into the regression equation model was the antisocial factor(OR= 2.100, 95% CI: 1.26-3.50); using “whether or not the participant was in the aggressive behavior group”as the dependent variable and the 4 factors clinical factors mentioned as the covariant. The final factors entered from the HCR-20 and PANSS into the regression equation model were C4 (impulsiveness) (OR= 7.134,95% CI: 2.96-17.21) and depression (OR= 1.291, 95% CI:1.07-1.56). (See table 5)

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

The results of this study did not find that unhealthy family environment or socio-demographic factors such as age, marital status, educational level, and history of illness were related to the aggressive behavior male inpatients with schizophrenia.

Previous studies have shown that past violent behavior was the most important and stable risk factor in predicting hospitalization and aggressive behavior from individuals with various mental disorders in the community.[4,7,14]The results of this study also lend evidence to this conclusion. This study shows that participants were prone to having conflict with the medical staff and the other patients followed by the occurrence of aggressive behaviors if they had previously attempted running away or quarreled with staff. The results are similar to the overall general clinical experience.

In terms of personality, inpatients with antisocial personality traits were prone to having aggressive behaviors. There are studies that show patients with schizophrenia with comorbid antisocial personality disorder had more brain damage (such as reduced volume of the thalamus) than patients with schizophrenia who have only mild antisocial tendencies.This brain damage can impact the transmission of sensory information and the ability to control impulses and behavior,[15]which may lead to increased display of aggressive behaviors.

Table 4. Comparison of the PANSS scores between the 2 groups (mean [sd])

Table 5. Regression model coefficient and its OR value (95%CI)

The manifestation of symptoms in participants who displayed aggressive behaviors was different than those participants who did not display aggressive behaviors.[16]In general, hallucinations and delusions were thought to be major factors that influencing the occurrence of the aggressive behavior in schizophrenia.[16]However,this study did not find a strong correlation between positive psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior.Some scholars believe that symptoms such as anxiety,depression, agitation, tension, and anger manifesting in the context of hallucinations and delusions were the key reasons for aggressive behavior in patients with psychosis.[18]Other psychiatric symptoms related to aggressive behaviors in participants were paranoia,activation syndrome, and impulsiveness, a finding which is consistent with previous studies.[16,19,20]

4.2 Limitations

This study had the following limitations: (a) previous studies had shown that there was gender differences in aggressive behavior when examining individuals with mental disorders, however, this study did not include female participants. Therefore there was no comparison between genders. (b) There was also a limitation in terms of disorders examined in this study.All the participants in this study had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and patients with other mental disorders(including those who had schizophrenia but also comorbid anxiety, depression or mental retardation)were excluded. (c) All participants of this study came from the same psychiatric unit of our general hospital.Further studies should include a more diverse sample including data from patients with schizophrenia in general hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and forensic hospitals. (d) In this psychiatric unit, patients with a comorbid substance use disorder are relatively rare. Given this study’s small sample size, it could be hard to detect the relationship between aggressive behavior and comorbid substance abuse. (e) ‘Aggressive behavior’ or risk of aggressive behavior was one of the criteria for involuntary admission, however there was no exploration of the correlation between involuntary admission and aggressive behavior. (f) This study was cross-sectional only, there was no further follow up with patients afterwards, therefore the predictive validity of factors we found related to aggressive behavior could not be verified in relation to actual violence in the future.

4.3 Implication

At present, there are quite a few studies (both in China and abroad) that explore the characteristics of aggressive behavior in hospitalized individuals with mental disorders. In general, it was believed that aggressive behavior could be predicted using factors such as socio-demographic characteristics or clinical manifestations.[3,6]However, the situation in China is different than in many places around the world in terms resources, provision of care and legal priorities,therefore research published abroad may not always apply in our local context.[21]Previous research published in China on this topic mostly explored patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, substance abuse, family environment, personality traits, or clinical pathology.[6]However, these factors were not comprehensive enough.

In view of the results of our study, the following factors should be considered when evaluating male inpatients with schizophrenia for aggressive behavior:(a) close attention should be paid to patients with aggressive history of violent or antisocial behavior;(b) individuals with mental disorders associated with antisocial traits may be prone to aggressive behavior.Additionally, previous studies have suggested that having schizophrenia with comorbid borderline personality disorder may also increase the risk of aggression in patients with mental disorders.[22]Therefore, performing a comprehensive personality assessment when patients with mental disorders are hospitalized is necessary.(c) Clinical symptoms (as measured using PANSS) had a higher correlation with aggressive behavior than did other demographic factors.[23]Therefore, clinical symptoms should also be taken into account when evaluating how at risk for aggression an individual may be. Furthermore, anxiety and depressive symptoms should be considered in the evaluation process, not merely positive psychotic symptoms.

Factors influencing aggressive behavior among this population are complex and diverse. This study provides data on factors associated with aggressive behavior in male inpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in hopes of improving safety and psychiatric service.

Funding

a) National Natural Science Foundation project.Project name: research on the correlation of schizophrenic patients’ hazard evaluation and the functional magnetic resonance resting state (project code: 81371500)

b) Project name: twelfth 5 year national science and technology support program (forensic identification key technology research). Sub-project (research on the risk assessment of violence in mental patients)(project code: 2012BAK16B04)

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Central South University Second Xiangya Hospital on 9thMarch 2013; approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Mental Health Center on 22ndOctober 2014.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors took part in the design of the project.Wen Li completed data collecetion, statistical analysis,and the article writing. Xiaoping Wang checked the paper.

1. Iozzino L, Ferrari C, Large M, Nielssen O, de Girolamo G.Prevalence and Risk Factors of Violence by Psychiatric Acute Inpatients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6): e0128536.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128536

2. Zhou JS, Zhong BL, Xiang YT, Chen Q, Cao XL, Correll CU, et al. Prevalence of aggression in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in China: A meta-analysis. Asia Pac Psychiatry.2016; 8(1): 60-69. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/appy.12209

3. Flannery R B Jr, Wyshak G, Tecce J J, Flannery G J.Characteristics of American assaultive psychiatric patients:review of published findings, 2000-2012. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3): 319-328. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9294-6

4. Witt K, van Dorn R, Fazel S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PLoS One. 2013; 8(2): e55942. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055942

5. Belli H, Ural C. The association between schizophrenia and violent or homicidal behaviour: the prevention and treatment of violent behaviour in these patients. West Indian Med J. 2012; 61(5): 538-543

6. Chen Q, Zhou J. [Aggression of Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review].Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;37(7):752-756. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.07.019

7. Dack C, Ross J, Papadopoulos C, Stewart D, Bowers L. A review and meta-analysis of the patient factors associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2013; 127(4): 255-268. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acps.12053

8. O’Shea L E, Thaker D K, Picchioni M M, Mason F L, Knight C, Dickens G L. Predictive validity of the HCR-20 for violent and non-violent sexual behaviour in a secure mental health service. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2015; Epub ahead of print.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1967

9. O’Shea L E, Picchioni M M, Mason F L, Sugarman P A,Dickens G L. Differential predictive validity of the Historical,Clinical and Risk Management Scales (HCR-20) for inpatient aggression. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 220(1-2): 669-678.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.080

10. Xiao Q, Li C, Wang XP. [Study of the reliability and validity of hcr-20 for assessing violent risk of patients with schizophrenia]. Yi Xue Lin Chuang Yan Jiu. 2010;27(3):405-408. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-7171.2010.03.006

11. Liu BH, Huang XT, Lv XW. [A preliminary study on the mental illness of criminals]. Xin Li Ke Xue. 2010; 33(1):223-225. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.16719 /j.cnki.1671-6981.2010.01.051

12. Decuyper M, De Fruyt F, Buschman J. A five-factor model perspective on psychopathy and comorbid Axis-II disorders in a forensic-psychiatric sample. Int J Law Psychiatry.2008; 31(5): 394-406. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.08.008

13. Xie B, Zheng ZP. [Modif i ed Overt Aggression Scales(MOAS)].Zhongguo Xing Wei Yi Xue Ke Xue. 2001;10(special issue):195-196. Chinese

14. Di Giacomo E, Clerici M. Violence in psychiatric inpatients.Riv Psichiatr. 2010; 45(6): 361-364

15. Kumari V, Das M, Taylor P J, Barkataki I, Andrew C, Sumich A, et al. Neural and behavioural responses to threat in men with a history of serious violence and schizophrenia or antisocial personality disorder. Schizophr Res. 2009; 110(1-3):47-58. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.009

16. McNiel D E, Binder R L. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry.1994; 45(2): 133-137

17. Wang XP. [Research progress of attack behavior]. Guo Wai Yi Xue Jing Shen Bing Xue Fen Ce. 1995; 22(1): 23-27. Chinese

18. Taylor PJ. When symptoms of psychosis drive serious violence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998; 33(Suppl 1): S47-54

19. Cornaggia C M, Beghi M, Pavone F, Barale F. Symptom dimensions as predictors of clinical outcome, duration of hospitalization, and aggressive behaviours in acutely hospitalized patients with psychotic exacerbation. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2010; 6: 72-78. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1745017901006010072

20. Darrell-Berry H, Berry K, Bucci S. The relationship between paranoia and aggression in psychosis: A systematic review.Schizophr Res. 2016; 172(1-3): 169-176. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.009

21. Imai A, Hayashi N, Shiina A, Sakikawa N, Igarashi Y. Factors associated with violence among Japanese patients with schizophrenia prior to psychiatric emergency hospitalization:a case-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2014; 160(1-3): 27-32. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.016

22. Volavka J. Comorbid personality disorders and violent behavior in psychotic patients. Psychiatr Q. 2014; 85(1): 65-78. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9273-3

23. Cornaggia C M, Beghi M, Pavone F, Barale F. Aggression in psychiatry wards: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res.2011; 189(1): 10-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.024

Wen Li graduated from the Central South University Second Xiangya medical school in June 2013 and acquired her master’s degree in the Central South University Second Xiangya medical school in June 2016. Currently, she is a graduate student in the Mental Health Institute of the Second Xiangya Hospital in Central South University. She started work in the psychiatry department in the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University in July 2016. Her research interests are aggression risk assessment in patients with mental disorder and biostatistics.

Xiaomin Zhu graduated with her bachelor’s degree in clinical medicine from the Sun Yat-sen University of Medical Sciences in June 2004. She acquired her master’s degree in medicine from the Sun Yat-sen University of Medical Sciences in June 2007. She acquired her PhD in psychiatry and mental health from the Central South University Second Xiangya medical school. She received joint training for doctoral students at Yale University from September 2014 to September 2015. She was an exchange student in the College of health and Life Sciences in Macao University from January 2016 to June 2016. She worked as the psychiatric resident and attending physician in the Xiamen Xianyue Hospital from July 2007 to August 2012. Currently she works as an attending physician in the psychiatry department in the Soochow University Affiliated Guangji Hospital. Her current research interests are forensic psychiatry and mental disorders in women.

男性住院精神分裂症患者的攻击行为特征研究

朱晓敏,李雯,王小平

攻击行为;精神分裂症;住院患者;社会心理学特征;病例对照研究

Background:The incidence of the aggressive behavior is higher among the patients with severe mental disorder such as schizophrenia than the general population. The study of factors related to aggressive behavior has great meaning in designing prevention and intervention methods with this population of patients.Aims:To understand the characteristics of assaultive behavior of male patients with schizophrenia who have been hospitalized.Methods:Using a continuous sampling method, data from 75 male inpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia was collected at the psychiatric unit of Central South University Second Xiangya Hospital(Changsha, China) from August 2015 to February 2016.On the third day after hospitalization participants were given a general questionnaire as well as being assessed using the modified overt aggression scale(MOAS), historical clinical risk management-20 (HCR-20) questionnaire, hare psychopathic checklist-revised(PCL-R), and positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS).Based on results of the MOAS participants were group into an ‘aggressive behavior’ group (39 cases) and ‘non-aggressive behavior’ group (36 cases).The differences in socio-demographic characteristics and scores on the other evaluation tools were then compared between these two groups.Results:Participants in the ‘aggressive behavior’ group had significantly different scores in the HCR-20 in the H1 (past violence events), H2 (violent events when young), H10 (disobedience in the past), and C4(impulsiveness) sections; as well in the anti-social section of PCL-R; and significantly higher PANSS scores in the positive symptom, depressive symptoms and paranoid symptom sections than those in the ‘nonaggressive behavior’ group.Conclusions:A combination of adverse and traumatic life events such as a history of violence, vulnerabilities in ones personality (e.g. impulsive or antisocial tendencies) and psychopathology of current illness (e.g.significant anxiety and depressive symptoms) contribute to aggressive behavior in male inpatients with schizophrenia. Our results contribute to the literature that will hopefully aid in ensuring patient and staffsafety, as well as providing more information in working with this vulnerable population.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016; 28(5): 280-288.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216052]

1Mental Health Institute of the SecondXiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

2Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Lanzhou, China

3Soochow Psychiatric Hospital, the affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University

#equal contribution to the paper

*correspondence: Dr. Xiaoping Wang. Mailing address: Institute of Mental Health, Xiangya No.2 Hospital, Central South University, 139 Middle Ren Min Road, Changsha, Hunan Province, China. Postcode: 410000. E-Mail: xiaop6@126.com

背景:精神分裂症等重性精神障碍患者攻击行为发生率高于普通人群,相关因素的探讨对于该人群攻击行为的预防和干预有重要意义。目的:了解某综合医院精神科男性住院精神分裂症患者的攻击行为特征。方法:采用连续取样法,收集了75例自2015年8月至2016年2月在中南大学湘雅二医院精神科男病房住院的精神分裂症患者。使用自编的一般情况调查问卷、修订版外显攻击行为量表(MOAS)、暴力历史、临床、风险评估量表(HCR-20)、精神病态清单(PCL-R)、阳性与阴性症状量表(PANSS)在入院后3天内对患者进行评估。根据MOAS各项的得分,将研究对象分为攻击组(39例)和非攻击组(36例),比较两组间在社会人口学特征以及各个评估工具上得分的差异。结果:HCR-20中的H1(既往暴力事件)、H2(年轻时的暴力事件)、H10(既往不服从管教)、C4(冲动性),PCL-R的反社会因子,PANSS的激活性症状群、偏执症状群、抑郁症状群在攻击组得分高于非攻击组,且差异有统计学显著性。结论:有暴力行为史,既往不服管教,具有反社会人格特征,表现冲动,伴有焦虑抑郁情绪可能是男性住院精神分裂症患者发生攻击行为的相关因素。

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Efficacy of atypical antipsychotics in the management of acute agitation and aggression in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: results from a systematic review

- Factors associated with significant anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women with a history of complications

- Brain gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentration of the prefrontal lobe in unmedicated patients with Obsessivecompulsive disorder: a research of magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- A pilot longitudinal study on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia

- The history, diagnosis and treatment of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Modern methods for longitudinal data analysis, capabilities,caveats and cautions