Reading the Four Books with Aristotle: A Hermeneutical Approach to the Translation of the Confucian Classics by François Noël SJ (1651—1729)*

Henrik Jaeger University of Freiburg

Abstract: François Noël SJ (1651—1729) published the Libri Classici and the Philosophia Sinica in the very complicated context of the last decades of the Rites Controversy. In his spiritual fi ght for an accommodation that would allow Chinese Christians to be both Chinese and a member of the Roman Church, he searched for a hermeneutical approach to read the Confucian Classics with Aristotle. Therefore his translation was rather free — he tried to make a synthesis of Confucian text and Aristotelian ethics, not a translation in the literal sense. This synthesis was able to display meaningful similarities between the two cultures and universal truths above the cultures. It was this synthesis that inspired philosophers as Christian Wolff, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Voltaire. This is clearly a concept of reason that is not yet imprisoned by colonial or postcolonial thought, it is an example of a fruitful discourse in a time, when intercultural exchange was not yet defined by western modes of thought.

Keywords: Jesuit accomodation politics in China; Scholasticism; Neo-Confucianism; Hermeneutics; Aristotelian Ethics; Early Enlightenment

2. The same year, Noël published the Philosophia Sinica tribus tractatibus:

A. De cognitione primae entis seu Dei apud Sinas(About the recognition of the fi rst being or GOD in China)

B. De Ceremoniis Sinarum erga Defunctos(About Chinese ceremonies for the dead)

C. Ethica Sinensis (Chinese ethics).

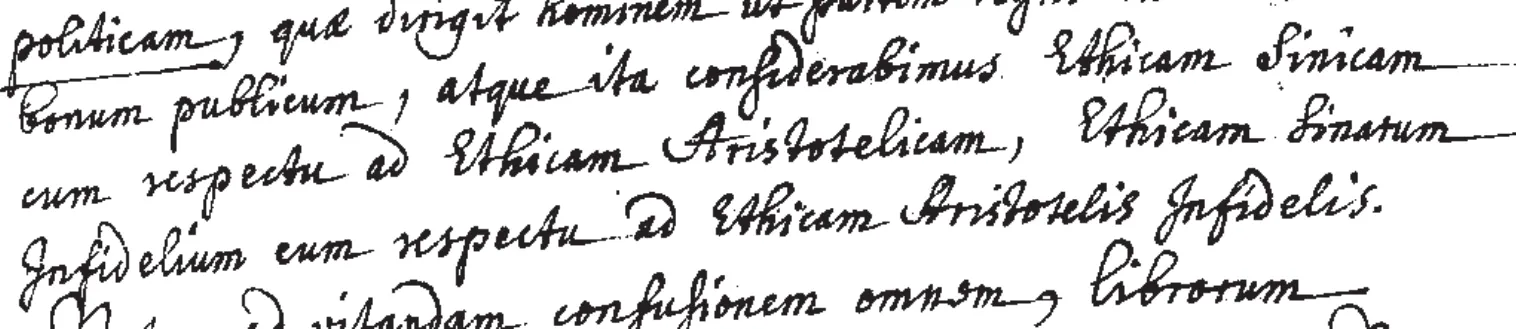

3. In his Ethica Sinica Noël links the central topics of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (NE) to the Confucian Classics, i.e. the Classics are transformed into a commentary to the NE and vice versa. In this “interweaving of texts” there is nearly no theological argument or citation to be found: It seems that Noël presented Chinese Philosophy as philosophy: “We will consider ethics of the unbelieving Chinese from the perspective of the ethics of the unbelieving Aristotle.” (ita considerabimus Ethicam Sinarum ad Ethicam Aristotelis In fi delis)

4. The fact that Noël regarded Aristotle as a “hermeneutic framework” for the interpretation of the “Four Books” raises an important question: Which Aristotle did Noël have in mind?How did he read the commentary of St. Thomas (or the Conimbricenses, Barbay, Suarez and others)?

5. The all-embracing signi fi cance of Aristotle in medieval and Renaissance Europe was naturally“transported” by the Jesuits into the context of the China mission as well: Aristotle served as a philosophical “bridge” between Jesuit scholasticism and Neo-Confucian philosophy in the Ming/Qing Dynasties.

6. When in his interpretation Noël made extensive use of Aristotelean modes of thinking, he could rely on a quite impressive tradition of a “Chinese” Aristotelianism (for example the 《修身西学》by A. Vagnone — a treatise about the Nicomachean Ethics with Confucian terminology).

7. The clear distinction between philosophical and theological issues was certainly typical for the Jesuit mission in general (cf. the importance of science and handcraft for the mission). But it was no “invention” of the Jesuits: rather, it goes back to St. Thomas’ interpretation of Aristotle.

8. This interpretation was in itself the fruit of a multifaceted encounter between Western Christianity and Islamic and Jewish philosophy: The rise of scholasticism in the 11/12th centuries (Albertus Magnus, St. Thomas) was basically linked to the question of the “right”interpretation of Aristotle’s philosophy.

9. In the process of solving these questions, esp. regarding the interpretations of Averroës (1126—1198), Thomas tried to clearly separate the philosophical and the theological realms in order to create a common ground for communication with the “pagans” (cf. his Summa contra gentiles).

10. Ultimately, it was the encounter with a non-European culture within the hermeneutic framework of Aristotle’s texts that evolved into a philosophical debate centered on the notion of “natural reason” (natura rationalis).

11. Confucius’s transformation, in the interpretation of the 16th century Jesuits, into an “apostle of reason” shows the same pattern of “struggling” with non-European modes of thinking as it had been the case in the 12th century.

12. Noël’s reading of the Sishu follows this Thomistic pattern: He tries to explain the classics in a way that treats them as a philosophical heritage in order to create a space of communication with the Confucian literati (esp. the converted!)

13. These few observations, however, still do not answer the main question a sinological researcher must pose here: What did Noël do about those aspects of the text that did not fi t into this pattern? Was he aware of this problem at all?

14. Could he find new meanings in Aristotle from the Confucian perspective, esp. from the perspective of Zhu Xi? These questions are the main topics of my current research project.

1. François Noël and the Libri Classici

The completion of the 125—year project to translate the Four Books in their entirety into Latin is due to a Belgian Jesuit: François Noël (1651—1729) — his Sinensis Imperii Libri Classici Sex are an outstanding example of a “philosophical translation” that tries to “translate worlds,not words” (R. Goldin). However, Noël’s Libri Classici didn’t receive much scholarly attention until today.This “vanishing into obscurity” has perhaps historical and philosophical reasons: On the one hand, Noël’s hermeneutical approach that was based on the idea of Aristotelian “reason”lost its significance in the age of Enlightenment, when the very concept of “reason” became fraught with colonialist notions of the superiority of the Western world. On the other hand, the tragic ending, in 1715, of the Jesuit politics of accommodation was also the turning point for a Chinese Christian community as the Jesuits had conceived it. Thus, in both China and Europe the Libri Classici were denied the space and the time to exert their influence and to be recognized as a monumental achievement of the Jesuit translation project. In this paper I will describe a few aspects of the philosophical background of Noël and their effects on his translation of the Sishu.Highlighting these aspects should allow to gain a more concrete insight into what it means “to read the Four Books with Aristotle.”

As T. Meynard has remarked in regard to the Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, the translation work of the Jesuits was an encounter of two living commentary traditions.The basic difficulty in describing this meeting lies in the complexity of both traditions. They both refer to a point in antiquity (Aristotle-Confucius/Mencius), they both regard a medieval commentary as “normative” (Thomas Aquinas, Zhu Xi), and they both are facing a multitude of different interpretations in the present. This complexity often results in a considerable difficulty to decide whether Noël, in any given passage, is employing an original concept of Aristotle’s or its scholastic interpretation by Thomas Aquinas or by later commentators.In short: when Noël interpreted the Confucian Classics, his understanding of Aristotle was shaped by the rich scholastic tradition of fi ve centuries.

Within this tradition, the controversy between reason and faith was a central issue from the 12th through the 17th century. The rise of scholasticism in the 12th century (Albertus Magnus,St. Thomas) was basically inspired by the commentaries of Averroës (Ibn Rushd; 1126—1198). In these commentaries covering the whole of Aristotle’s heritage Averroës stressed the autonomy and independence of reason in regard to religious authorities. In his interpretation of Averroës, Thomas Aquinas tried to separate the philosophical from the theological realm in order to create a common ground for communication with the “pagans” (cf. his Summa contra gentiles). In this way, the idea of reason implied the possibility and the necessity to communicate with the Muslim and the Jewish world.

In other words, from its very beginning, the broad reception of Aristotle from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance implied an intercultural horizon. In this period Aristotle was translated from the Arabic and Greek into Latin and Hebrew, so that the encounter of the Jesuits with the Confucian literati and the fi rst translations of works such as De Anima and the Ethica Nicomachea into Chinesewere a natural consequence of Aristotle being conceived of as a “metacultural” philosopher,whose thought was regarded as limited by neither temporal nor cultural circumstances.

The hermeneutical approach of the Libri Classici bears a close resemblance to both Chinese and Western commentary literature: Important commentaries tend to carry a great number of“distorted” interpretations, nevertheless they were greatly influential in their time and shaped the understanding of the underlying text for generations. Be it Confucius’ interpretation of the Shijing, Guo Xiang’s commentary of the Zhuangzi, Zhu Xi’s Sishu jizhu or Thomas’s commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics, it is easy to show that the respective commentator came forth with interpretations that were in some cases totally alien to the original text. Nevertheless, their interpretation re-positioned the text in the context of their time. This positioning somehow enabled the “world of the text” and the “world of the reader” (Paul Ricœur) to “mirror” each other. The text thus took on a contemporary meaning that continued to inspire other interpretative and philosophical works for centuries to come. The Libri Classici have the same background and possess the same functions as a commentary. In fact, in large parts of the work (esp. in the Mengzi translation), Noël’s interpretation is directly based on a specific commentary: The Sishu zhijie written by Zhang Juzheng which, together with Zhu Χi’s commentary, had a great in fl uence on Noël’s Latin version.Thus the Libri Classici can be considered an example of the “interweaving”of two commentary traditions that aimed at making the Four Books meaningful for Europeans as well as for Chinese Christians!

2. Historical Background

François Noël entered into China in 1687, in an era, in which the Jesuit Mission had been able to create a rich culture of exchange between western and Chinese scholars. Jesuits had written a lot of treatises on western science and philosophy. They had translated Greek and Latin classics into Chinese. They were working on translations of Chinese classics, esp. the Sishu and the Yijing.

All this work was intended to become a bridge between the cultures and to allow new forms of accomodation. Their aim was incredibly ambitious — to convert the emperor himself and with him the whole empire.

François Noël seems to have studied not only the Chinese Classics very well and quickly, but he developed also a keen sense of the Commentary tradition, of the philosophical debates under the Kangxi emperor; moreover he gained deep insights into the “otherness” of Chinese language and thought. Moreover, he was the fi rst western scholar who interpreted Zhu Χi from a theological perspective and he made his translation with a transcultural outlook. In his Libri Classici he tried to transmit the sense of the Confucian classics to Western readers and to Chinese Christians simultaneously. Thus Chinese philosophy gained a universal meaning as it became readable in Europe of the early Enlightenment Era.

François Noël was born in Herstrud (Belgium) in 1651, in 1670 he entered into the Jesuit order and for four years he studied in Douai (Lille), where he displayed great literary talents. From 1687 he lived in Southern China (Nanchan, Nanan), where he did a lot of missionary work in the lower classes and simultaneuosly studied and translated the Classics.

In 1702 he was appointed together with the Jesuit mathematician Kaspar Castner (1665—1709) as procurator by the vice-provincial Antoine Thomas and was sent to Rome to convince the Pope about the compatibility of the Chinese rites (and thought) with the Christian faith. Noël was back in Macao in 1707, but did not remain long in China as he was sent with several others(i.e. Loius Fanshouyi, the fi rst Jesuit Father who studied theology in the West) as special envoys of the Kangxi emperor to Europe. In Rome Noël again participated the Chinese rites debate, but soon after 1709 he went to Prague where he remained until 1713. It was during these years that he prepared his sinological works for the press, among which were the Sinensis imperii libri classici sex and the Philosophia sinica tribus tractatibus. These works disappeared very quickly after their publication, perhaps they were forbidden by the church in order to calm down the Rites controversy. In 1716 François Noël once more tried to go to China from Lisbon but was forced to return. He moved to his hometown Lille and died there in 1729.

A very astonishing point of his later life is that he didn’t write anything more about China or Chinese philosophy after the publication of his books in Prague. In the 18 years between 1711 an 1729 he seems to have completely neglected his enormous sinological knowledge, that was so outstanding, that contemporary voices said that there “rarely was a person in his time who could be compared to him.”

Another signi fi cant trait of his translations and interpretations is a high level of complexity and sophistication. If they had the opportunity to be acknowledged in China and in the West, they could have developed into a fi rm ground for a Chinese theology and in the same time as a model for a philosophical interpretation of Chinese Philosophy.

3. “We will consider ethics of the unbelieving Chinese from the perspective of the ethics of the unbelieving Aristotle”

In his Ethica Sinica, Noël gives a systematic account of Chinese ethics within the framework of a teaching manual of the Nicomachean Ethics, thus attempting to link the Confucian classics(esp. the Sishu) to the commentary tradition of the Nicomachean Ethics (further: NE). There are some interesting points in the Ethica Sinica that should be considered:

1. Like the Libri Classici, this tract is virtually devoid of theological terms and biblical quotations.

2. Noël sees a lot of resemblances between the NE and the Chinese text, but there are also interesting observations as to the differences between Aristotelianism and Confucianism.

3. Noël also cites ren-yi-li-zhi 仁—义—礼—智(the Confucian Virtues) and regards them as equal to the Aristotelian virtues

4. Because Noël is fully aware of the problem as to how to produce an exact translation of a given term, he often puts Latin terms in parallel with Chinese texts, thus mapping out a broader semantical space.

5. The Confucian virtue of zhi 智(prudence) is central to the NE as well: the speci fi c kind of knowledge and insight that Aristotle calls “practical wisdom” has many parallels in Chinese philosophy.

In the following, in order to give a more concrete idea of the manner in which Noël reads a Chinese text from the viewpoint of Aristotle, I would like to give a short introduction into the meaning of prudence in the NE and the way it is applied to the interpretation of Mencius.

4. “Prudence” (Practical Wisdom) in the Nicomachean Ethics

“Prudence” is a core concept that has seen many quite different interpretations in the long history of interpreting the NE. “Practical Wisdom” involves a knowledge of good and bad that is not gained by theoretical deliberation but by intuition, experience, the understanding of traditional values, and the personal ability to ponder on all the aspects of a given situation. This means that it requires:

1. a general conception of what is good and what is bad, which Aristotle relates to the conditions of the fl ourishing of human beings.

2. the ability to perceive, in the light of that general conception, what is required in terms of feeling, choice, and action in a particular situation.

3. the ability to deliberate well; and

4. the ability to act on that deliberation.

Practical wisdom cannot be taught because it requires experience and virtue: only the person who is good knows what is good. Aristotle argues that practical wisdom requires different kinds of insight. First, there should be insight into “what is good or bad for man,” i.e. insight into the flourishing of human beings. Second, practical wisdom requires understanding of what is good in a particular situation within the general idea of the good.There are no general rules for applying knowledge to any current situation. This makes it impossible to make true generalizations about right and wrong, good and bad. Rather, our ethical deliberation is a kind of intuitive reasoning that combines subjective insight with objective aspects such as values and circumstances. Furthermore, this kind of insight is inseparable from making a good decision: we should not only understand the situation, but also decide to act in a good way.A third kind of insight relates to what is virtue. If we feel emotions and desires and make decisions “virtuously,” we feel and choose “at the right times, with reference to the right objects, towards the right people, with the right motive,and in the right way.” These aspects are combined in the superb definition Aristotle has given in NE, II, 6:

eoτιν aρα n aρετn eξις πρoαιρετικn, eν μεooτητι ouoα τn πρoς nμaς, wριoμeνn λoγw καi waν o φρoνιμoς oρioειεν.

Virtus est habitus electivus consistens in mediocritate ea qua est ad nos, definita ratione,& prout vir prudens de fi nierit. (translation used in the Coimbra-Commentary)

Virtue, then, is a habit or trained faculty of choice, the characteristic of which lies in moderation or observance of the mean relatively to the persons concerned, as determined by reason, i.e. by the reason by which the prudent man would determine it. (tr. Peterson)

We may now de fi ne virtue as a disposition of the soul in which, when it has to choose among actions and feelings, it observes the mean relative to us, this being determined by such a rule or principle as would take shape in the mind of a man of sense or practical wisdom. (tr.J.A.K. Thomson)

In this de fi nition of virtue; practical wisdom is linked to the sophisticated teaching of mesotes(the mean), a notion that is in fact rooted in medicine in much the same way the idea of zhongyong中庸 (the mean) is derived from medical knowledge. Consequently, Aristotle’s de fi nition is contextualized by Noël precisely with the zhongyong in order to describe the Chinese understanding of virtue.In his section about practical prudentia (wisdom) Noël also quotes several passages from the Zhongyong and from the Mengzi. In some of these passages the Chinese term zhi 智 doesn’t occur, but nevertheless “prudence” is used by Noël in order to “commentate” the text under the perspective of practical wisdom.

5. Interpreting the Mencian idea of “holding to the mean without weighing up” 执中无权

In Mengzi 7 A, 26 the extreme attitudes of egotism (such as Yang Zhu’s) and altruism (as in the case of Mozi) are described. A certain Zimo boasted of having found the exact “mean” between these extreme attitudes. Mencius’ commentary on Zimo’s self description is rather negative, he reproaches Zimo for “holding to the mean”:

子莫执中。执中为近之,执中无权,犹执一也。

Nostri autem Regni Lu celebris incola Zimo mediam inter hos duos Sectarios viam elegit;nec boni publici curam respuit, ut Yang Zhu; nec se neglecto unam aliorum utilitatem caeco studio aequaliter quaesivit, uti Mozi; sed Medium tenendo; putavit se a recta rectae rationis via non procul recedere. Si tamen in arrepto duorum Sectariorum Medio prudentiam, quam locus, tempus & res exigunt, non servarit; etiam vel sic unam partem aut dextram aut laevam,non autem verum Medium arripuisse dicetur.

Zimo, a citizen of our famous kingdom of Lu, had chosen the Middle Way between these two extreme attitudes. He didn’t refuse to care for society like Yangzhu, nor did he neglect himself out of blind eagerness to further the advantage of others, like Mozi did. Through holding to the Mean he thought to be close to the right way of right reason (recta ratio). But in this way he held too fast to the Mean and neglected prudence (prudentia), which weighs up place, time and circumstances. Because of this lack of prudence it should perhaps be said that he held only a part, the right or the left, but not the true Mean.

In this passage, the same idea as in NE II, 6 (cited above) is expressed: the “mean,” the right decision and in the end the virtual habituation are impossible without “weighing up,”with sensitive, intelligent and experienced deliberation. The practical wise man, the phronimos,exercises his good sense, he is not one-sided, and because he has a keen sense of the polarity of each situation, he is also a good judge: He knows how to “hit” the true Mean that is the best way to deal with any given situation.

In his introduction to the Philosophia Sinica Noël also quotes the famous passage from the Mencius that describes in a very direct way his hermeneutical method:故说诗者,不以文害辞,不以辞害志。以意逆志,是为得之。

Hence in explaining an ode, one should not allow the words to obscure the sentence, nor the sentence to obscure the intention. The right way is to meet the intention of the writer with one’s sympathetic understanding. (Mengzi 5A, 4)

Prudens libri Carminum interpres non debet abuti nudis verbis ad nocendum sententiis;nec nudis sententiis ad nocendem sententiarum sensui.

The prudent interpreter of the Book of Songs should not with bare words damage the sentences, nor should he with bare sentences damage the sense of these sentences.

In other words, for Noël, the translation or interpretation of the Chinese text was likewise a very sensitive and demanding creative task that required the wisdom of a “wise” judge. In this manner, the Libri Classici were the fruit of the practical wisdom of all the peoples of East-Asia and an appeal to the Europeans, “to put into life, what the Chinese for ages had felt in the right sense.”

6. Missionaries of Practical Wisdom from China?

Noël’s sinological works were written at a time when there was no discipline such as“Chinese Studies” or “Sinology,” which only began to take shape alongside the rise of colonialism in the 18th century. With his Libri Classici and the Philosophia Sinica, Noël had to give an answer on very dif fi cult political and theological problems posed by the Chinese authorities, the Holy See and the European intelligentsia. However, it was perhaps France’s intellectual elite that was most interested in all available details concerning Chinese culture and philosophy, for these forerunners of the Enlightenment were convinced that Confucius and his heritage could provide the solution to many problems of their own time. Especially in the fi elds of ethics and politics, China’s leading position was acutely felt. Most remarkable, and clearly indicative of this intellectual context, is perhaps Leibniz’s famous saying that the Chinese Emperor should send Confucian missionaries in order to teach the Europeans practical wisdom.

Such was also the essence of Christian Wolff’s “Discourse on the Practical Philosophy of the Chinese,” a lecture held in 1721 after nine years of careful study of the Libri Classici.Wolff’s admiration for the Confucian principle of experiment and proof, of the independence and autonomy of reason, and of the “marriage of experience and reason” (connubium experientiae et rationis) is only a few of the aspects he discovered in the Libri Classici.But the problem in evaluating Noëls influence on Wolff is the “Aristotelian” hermeneutical framework. From his youth in Breslau on, Wolff was well-versed in Scholasticism and had a deep understanding of Spinoza’s ethics, which is in fact an “averroistic” commentary on the NE. In other words, further research is needed to identify the extent to which Wolff was in fl uenced by this Confucianism in Aristotelian disguise.

But the sheer fact that Wolff (like many other forerunners of the Enlightenment) dedicated more than 30 years to the study of the Libri Classici gives an idea of the importance of the hand for shaping his thought. Moreover, it remains an astonishing fact that from the very beginning of scholasticism, the idea of “reason” had the function and the power to integrate the philosophies of non-European cultures: it had the function of building bridges. Aristotle’s philosophical heritage was considered a guarantor for the possibility of an integrative approach to Muslim, Jewish and, finally,Chinese philosophy.

After his great “teacher” Leibniz, Christian Wolff was perhaps the last “scholastic” whose idea of reason was broad enough to create a space of communication between cultures. This breadth of thought changed into its exact opposite in the following decades of the Enlightenment.Kant and Hegel, for instance, were instrumental in the devaluation of Chinese philosophy and its extrication from the European consciousness. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the concept of “reason” became an agent of building walls—and this fact, together with an overarching conviction of being part of a superior civilization, determines our attitude toward Chinese philosophy to this day. It would be interesting to ask what François Noël could tell us in this present state of affairs: what we could learn from a man who didn’t read the Classics with scienti fi c distance but with a humanistic passion intent on bringing the practical wisdom of the Confucian heritage from China to Europe.

- 国际比较文学(中英文)的其它文章

- 忧郁的辩证:本雅明对潘诺夫斯基之丢勒阐释的继承和发展*

- 中国古代题画诗文的社会功能及其发展的社会动因*

- 朝圣者的“冥府之行”—关于《埃涅阿斯纪》与《神曲》“冥府之行”主题四个片段的比较文学解读* #

- Literature and Cosmopolitan Imaginings: On the Diasporic Representation and Imaginary Cosmopolitanism in America is in the Heart and “One out of Many”*

- 苏格拉底葬礼演说中的德性与政制—柏拉图《默涅克塞诺斯》的哲学教育*

- 超越现实的小说与偏离小说的阐释*—卡尔· 施米特与赫尔曼· 梅尔维尔