Successful treatment of noncirrhotic portal hypertension with eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A case report

Alexandra Alexopoulou, Iliana Mani, Dina G Tiniakos, Flora Kontopidou, Ioanna Tsironi, Marina Noutsou,Helen Pantelidaki, Spyros P Dourakis

Alexandra Alexopoulou, Iliana Mani, Flora Kontopidou, Ioanna Tsironi, Marina Noutsou, Helen Pantelidaki, Spyros P Dourakis, 2ndDepartment of Medicine, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Hippokration General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece

Dina G Tiniakos, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Framlington Place, Newcastle NE2 4HH, United Kingdom

Dina G Tiniakos, Department of Pathology, Aretaieion Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 11528, Greece

Abstract

Key words:Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; Idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension; Eculizumab; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH) is evidenced by the presence of an increased portal venous pressure gradient despite the absence of a known cause of chronic liver disease and portal vein thrombosis[1]. In India, INCPH accounts for 23%of portal hypertension cases[2], while in the Western world, it is very rare[3]. The etiology is heterogeneous and varies according to the geographical area and the population studied[4,5]. INCPH is often misdiagnosed as liver cirrhosis, so liver histology is required to differentiate between the two entities[1]. Histological features in liver specimens from patients with INCPH include obliterative portal venopathy,hepatoportal sclerosis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, and incomplete septal cirrhosis[1]. It has been suggested that obliterative portal venopathy may represent an early stage while nodular regenerative hyperplasia is a late stage of the same disease currently termed porto-sinusoidal vascular disease[6], which may lead to INCPH[7].Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare disease[8]and has not been reported so far as a cause of INCPH. We herein describe a case of PNH complicated by INCPH, which was reversed clinically by the administration of eculizumab.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63-year old female patient was admitted to the hospital for fatigue, jaundice, and large-volume ascites.

History of present illness

PNH was diagnosed 2 years earlier when she was admitted for anemia, but she was lost to follow-up. Six weeks before current admission, portal vein thrombosis was diagnosed and enoxaparin 60 IU twice daily was initiated.

Physical examination

The abdomen was distended, and the liver was enlarged 4 cm below the right costal margin. The spleen was mildly enlarged.

Laboratory workup

Blood analysis revealed hemoglobin of 10.8 g/dL, white blood cell count 5.4 × 109/L,platelets 171 × 109/L, reticulocytes 6.5%, international normalized ratio 1.0, total bilirubin 4 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 2.6 mg/dL, aspartate transaminase 28 IU/L,alanine transaminase 12 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 456 IU/L, glutamyl transpeptidase 248 IU/L, total protein 6.6 g/dL, albumin 3.3 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 650 U/L, serum haptoglobin < 7 mg/dL, creatinine 1.7 mg/dL,urea 81 mg/dL. Ascitic fluid had a serum-ascites albumin gradient of 1.7 g/dL (ascitic fluid total protein 3 g/dL, albumin 1.6 g/dL). Hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. Direct globulin test was negative.

Further work-up

In Doppler ultrasonography of splenoportal axis, recanalization of the portal vein and large abdominal portosystemic anastomoses were evident. Hepatic veins were patent.Magnetic resonance imaging showed hepatomegaly and confirmed the above findings. No esophageal or gastric varices were demonstrated in endoscopy. Ascites was refractory to diuretics and multiple large volume paracenteses were required.Due to the absence of a clear etiology of portal hypertension, a liver biopsy was performed.

Liver histology

Changes of portal venopathy with portal fibrosis and sclerosis and features of nodular regenerative hyperplasia were demonstrated. A spectrum of portal vein lesions was seen in interlobular portal tracts included in the biopsy, ranging from portal venule herniation in the periportal parenchyma, to slit-like stenosed portal venules and sclerosed portal tracts without a visible portal venule. In addition, parenchymal ischemic changes indicative of decreased venous outflow, mild focal sinusoidal and perivenular fibrosis, mild cholestasis, and mild secondary siderosis were noted. There was no bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis (Figure 1). The overall changes supported the diagnosis of INCPH.

Hematology work-up

The flow cytometry at this point revealed that 16.5% of her red blood cells were PNH,4.1% were partially deficient for CD59, and 12.4% lacked CD59 completely; 63% of her granulocytes and 60% of monocytes were PNH.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

INCPH complicating PNH was diagnosed.

COURSE OF THE DISEASE

Paroxysms of abdominal pain, debilitating fatigue, dyspnea, deepening of jaundice(total bilirubin 21 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 14.4 mg/dL), worsening of renal function(creatinine 2.2 mg/dL), anemia (Hb 7.6 g/dL), and thrombocytopenia (80 × 109/L)developed over the next 8 weeks, and the patient became bedridden. Vaccination for Neisseria meningitis was performed as a prophylaxis for future therapy with eculizumab.

TREATMENT

Eculizumab was initiated at a regular dosing for patients with PNH (600 mg weekly for the first 5 weeks followed by 900 mg biweekly thereafter).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

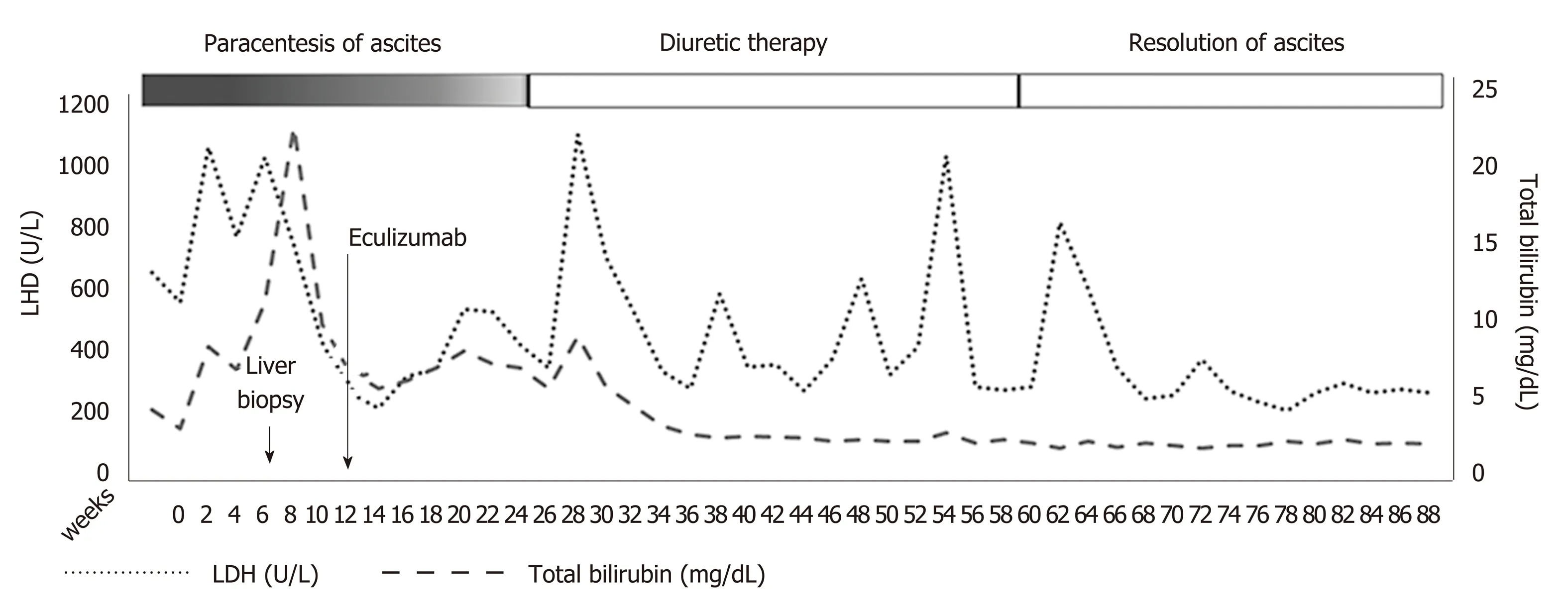

Three months following eculizumab initiation, no more therapeutic paracentesis of ascitic fluid was required and diuretics were administered. Serum bilirubin, LDH,hemoglobin, and reticulocyte count improved gradually (Figure 2). Renal function,serum bilirubin, LDH, and platelets normalized 6 months following initiation of eculizumab. One year later, diuretics were stopped without reappearance of the ascites. No direct antiglobulin test was evident during follow-up. Anticoagulation treatment with enoxaparin was continued during hospitalization and follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1 Selected images from the liver biopsy showing changes of portal venopathy and features of nodular regenerative hyperplasia.

Our patient fulfilled all the criteria for the diagnosis of INCPH, including the clinical signs of portal hypertension (ascites and portovenous collaterals in our case), the exclusion of cirrhosis on histology, the absence of chronic liver diseases causing cirrhosis or other conditions causing INCPH, and the patency of portal and hepatic veins[1]. Although called idiopathic, INCPH has been associated with various conditions, including thrombophilia[9], hematological malignancies[10], infections[11],medication and toxins[12], genetic[13]and immunological disorders[14]. The main symptoms of patients with INCPH are upper gastrointestinal bleeding and splenomegaly[2,15]. Ascites, as in the current case, was present in 50% of cases in a French[16]and in 26% in a Spanish study[17]. Prothrombotic disorders accounted for 48% in the former and 8% in the latter. Our case demonstrated the presence of large abdominal portosystemic collaterals. However, esophageal or gastric varices were not evident, probably due to the early stage of portal hypertension. Chronic ascites may be attributed both to portal hypertension and the concomitant renal failure in keeping with published literature[1]. Kidney disease is a common manifestation of PNH and is a result of tubular damage caused by microvascular thrombosis and renal iron accumulation[8].

From a pathophysiology point of view, in thrombophilia cases of INCPH, increased intrahepatic resistance ensuing from obliteration of the portal venous microcirculation may result in an increase in portal blood pressure[7,18]. High levels of endothelin-1 might further increase vascular resistance and stimulate periportal collagen production[19]. Another hypothesis is that the prothrombotic disorder affects the sinusoidal and portal vein wall causing fibrosis, obstruction, and secondary alterations in hepatic architecture[10]. In the case of PNH, the accumulation of high levels of free hemoglobin, which is a potent nitric oxide scavenger[20], may play a role in increasing vascular resistance. Nitric oxide maintains smooth muscle relaxation and inhibits platelet activation and aggregation[21]. Its deficiency may contribute to smooth muscle tone increase and platelet activation.

Figure 2 Clinical and laboratory course of the disease before and after treatment with eculizumab.

In PNH, deficiency of the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored complement regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59 induces the intravascular hemolysis that is the main clinical manifestation of the disease[22,23]. Thrombotic events occur in about 27%of patients with PNH and are the main cause of mortality, accounting for approximately 40% of deaths[24]. Hepatic and portal veins are considered common sites of thrombosis[25]. Eculizumab is a monoclonal blocking antibody to complement protein C5, which inhibits cleavage to C5a and C5b and impedes terminal complement complex C5b-9[26]. Trials with eculizumab demonstrated a reduction in hemolysis, stabilization of hemoglobin levels, and a reduction in transfusion requirements but also a protection against the complications of hemolytic PNH, such as deteriorating renal function, pulmonary hypertension, and thromboembolism[27].

The patient presented has a large clone (> 50% PNH granulocytes and > 10% PNH red cells) combined with a notably increased LDH as evidence of intravascular hemolysis and a high reticulocyte count. In addition, platelet count was normal and anemia was mild without transfusion requirement, indicating an adequate bone marrow reserve. Thus, she had many chances to benefit from eculizumab treatment as the drug is highly effective in abrogating the intravascular hemolysis of PNH and reducing the risk of thrombosis but does not alleviate bone marrow failure if present[28]. Eculizumab is expensive and should be administered indefinitely for achieving sustained response. It has been stated that the drug has changed the natural course of PNH[29].

In our case, long-term treatment with eculizumab in combination with anticoagulation in a patient with PNH and INCPH resulted in improvement of the symptoms of liver disease, elimination of intravascular hemolysis, gradual resolution of kidney disease, and improvement of quality of life. The beneficial effect of the drug on liver microcirculation may be a result of the elimination of the prothrombotic disorder and the decrease of vascular resistance of the sinusoidal and portal venous walls.

CONCLUSION

Long-term administration of the monoclonal antibody eculizumab controlled the symptoms and life-threatening complications of PNH. More specifically, it reversed the complications of INCPH, as indicated by the elimination of large ascites and jaundice and normalization of liver function tests. Furthermore, it abrogated the intravascular hemolysis and improved dramatically the quality of life.

World Journal of Hepatology2019年5期

World Journal of Hepatology2019年5期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Roles of hepatic stellate cells in acute liver failure: From the perspective of inflammation and fibrosis

- Hepatitis C virus cure with direct acting antivirals: Clinical,economic, societal and patient value for China

- Hepatitis C virus antigens enzyme immunoassay for one-step diagnosis of hepatitis C virus coinfection in human immunodeficiency virus infected individuals

- Expanding etiology of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- Carvedilol vsendoscopic variceal ligation for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding: Systematic review and metaanalysis

- Neonatal cholestasis and hepatosplenomegaly caused by congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type 1: A case report