Epidemiological survey on scorpionism in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran: an analysis of 1 067 patients

Hamid Kassiri, Elnaz Kassiri, Rahele Veys-Behbahani, Ali Kassiri

1Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3Medicine School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Epidemiological survey on scorpionism in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran: an analysis of 1 067 patients

Hamid Kassiri1*, Elnaz Kassiri2, Rahele Veys-Behbahani1, Ali Kassiri3

1Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3Medicine School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Objective: To study epidemiologic parameters of scorpion stings in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran, during 2006-2008. Methods: In this descriptive study, data were collected from health services center's files at Gotvand County. A special scorpion sting sheet was prepared. This sheet contained information about the site of scorpion stung, the date and place of the accident, the sex of the injured and etc. The frequencies of entomo-epidemiological characters were changed to the percentage basis. Results: Cases were collected from health services center's files over three years. There were 1 067 scorpion victims, 44.1% of whom were from rural areas. Stings occurred throughout the year, however, the highest and lowest frequency happened in August (12.5%), January (1.9%) and February (1.9%), respectively. About 41.9% of stings were on the feet and 38.8% on the hands. Stings mainly occurred in summer (35.3%) and spring (33.2%), respectively. The average of prevalence rate of scorpion sting in the county was 5.6/1 000 people. The scorpions responsible for the majority of stings were identified as 67.3% yellow, 20.2% black and 12.5% unknown colors. Conclusions: Scorpionism in Gotvand County of Khuzestan Province is a public health problem, which needs to be monitored carefully by the government.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 8 August 2013

Received in revised form 15 September 2013

Accepted 24 September 2013

Available online 20 November 2014

Scorpion sting

1. Introduction

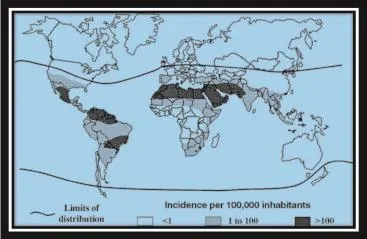

The scorpion stings are a common health problem in several regions of the globe; in particular in East of the Andes, Mexico, Latin America, Near and Middle-East, South India, North-Saharan Africa, Sahelian Africa and South Africa[1]. World distribution of scorpionism is illustrated in Figure 1. Scorpions’ venoms are extremely poisonous for humans. After subdermal injection in rabbit, the most serum density is attained in blood in under 2 h and about 70% of the venom of scorpion is found in the blood flow in under 15 min[2].

More than 1 200 000 scorpion stings occur annually while the number of deaths could exceed 3 250. Average case fatality rate is 0.27%[3]. Scorpion envenomation depends on various factors such as, the scorpion species, scorpion size, number of stings, bulk of the venom glands, status of the venom canals of the telson, the amount of venom injected, the age of the offender, victim’s age, victim’s weight, interval between envenomation and hospitalization, the anatomical location of the sting, victim’s health status and the season can be mentioned[4-6].

Across Middle Eastern countries, minimum 52 species of scorpions have been distinguished in Iran[7]. Scorpion sting cases are common in southern half of Iran, due to its climate, geographical situation and socioeconomic status[8-10]. The southwest and south of Iran with approximately 95% species of scorpions are the most compactly populated regions in the country[11,12]. Almost 45 000-50 000 scorpion stings are annually reported in Iran[13].

In scorpion fauna of Iran, the being of three scorpion families comprising Hemiscorpiidae (Liochelidae), Scorpionidae and Buthidae is reported. These three families comprise 22 genera, 52 species and 25 subspecies[14]. The families Buthidae, Hemiscorpiidae and Scorpionidaewith 82%, 9% and 9% of all the genera and 88.5%, 5.75% and 5.75% of all the species, respectively, are the most abundant in Iran. Also, the Androctonus (Buthidae) and Hemiscorpius (Hemiscorpiidae) genera have the highest medically importance[7]. In Iran reported that scorpions liable for sting are belongs to the species,Hemiscorpius lepturus,Androctonus crassicauda,Mesobuthus eupeus,Odontobuthus doriae,Hottentotta saulcyi,Hottentotta schach,Compsobuthus matthiesseni,Orthochirus scrobiculosus,Apistobuthus pterygocercusandOlivierus caucasicus[7,14,15]. Three species ofAndroctonus crassicauda,Mesobuthus eupeusandHemiscorpius lepturusplay a major role in about all cases of scorpionisms in Iran[13].

In Iran, the greatest prevalence rate of scorpionism and its consequence death has been reported from Khuzestan Province. About 60% of all scorpion sting reports emanate from this province. Based on the published data of the Disease Management Center, frequency distribution of scorpion sting in Khuzestan Province was specified 23 984, 22 847, 23 076, 20 434 and 24 876 from 2001 to 2005, respectively[16]. In 2009, the average incidence rate of scorpion sting was determined 59.5 per 100 000 individuals in Iran, however, the highest incidence rate was apperceived in Khuzestan Province (541 per 100 000 population)[17].

In a study on 418 victims in Khuzestan Province seven scorpionsAndroctonus crassicauda(28.7%),Hemiscorpius lepturus(24.9%),Mesobuthus eupeus(21.7%),Compsobuthus matthiesseni(20.6%),Hottentotta saulcyi(3.35%),Orthochirus scrobiculosus(0.5%) andHottentotta schach(0.25%) had the highest frequency.Hemiscorpius lepturusbelongs to Hemiscorpiidae with hematotoxic and cytotoxic venom and the rest appertain to Buthidae with a neurotoxic venom[18].Hemiscorpius lepturus(Figure 3) is one of the most perilous species of scorpion in the globe. This species is famous for possessing a strong cell-toxic venom that causes psychological difficulties, intense systemic pathology conducting to dying, profound wounds, dermal necrosis, deadly and severe hematolysis, secondary failure of the kidneys, deadly renal failure and ankylosis of the joints[15,19,20].

Figure 1. Scorpionism areas of the globe (prepared by J.-P. Chippauxa and M. Goyffon).

Figure 2. Map of IRAN Provinces, the Khuzestan Province displayed in black color (Prepared by National Geosciences Database of IRAN).

Figure 3. A photo illustration of male and female H. lepturus (Prepared by MH Pipelzadeh et al).

As far as we know, no study exists to survey the situation of scorpionism in Gotvand County, Khuzestan province, Iran. This study was conducted to determine the epidemiology of scorpion stings in this region. These data are important for the control of stinging by scorpions.

2. Materials and methods

Gotvand County (32°15′05″N 48°48′58″E, altitude ca. 599 m asl) is a county in Khuzestan Province (Figure 2) in southwestern Iran. It was separated from Shushtar County in 2005. At the 2006, the county’s population was 58 311, in 11 440 families.

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study of the medical records of all people diagnosed with scorpion envenomation who were admitted to Gotvand health services centers over a 3-years period extending between 2006 and 2008. The cases were monitored after their physical and history examination. The information of 1 067 patients for the presentresearch was assigned into epidemiological features. The epidemiological information included: data on the place and date of the sting accident, the anatomical sting location, the gender of the victim, the color of scorpion, interval between sting and antivenin injection, sting scorpion history and history of receiving antivenin. In terms of site of the sting event, villages were noticed to be rural regions, and town was noticed to be urban regions. Data were analyzed using a SPSS computer package by using descriptive statistics.

3. Results

The total number of patients surveyed in Gotvand County over the research period was 1 067. The average rate of sting incidences in three years was calculated 5.6/1 000 inhabitants. The incidence of scorpionism was estimated 5.5, 5.4 and 5.8 in the years of 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively. Also, the highest affected cases were observed in 2008 (372), 2006 (348) and 2007 (347), respectively. Of the victims, 51.8% (n=553) were males, and 48.2% (n=514) were females. The details of sex distribution of the scorpion victims are presented in Table 1. In all, 44.1% (n=471) and 55.9% (n=596) of the persons were from rural and urban regions, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by sex in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006-2008).

Table 2. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by sting place in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006 -2008).

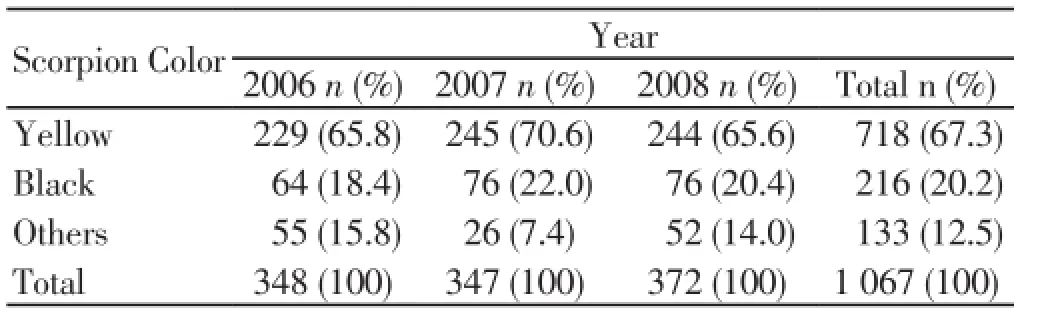

As can be observed in Table 3, of the aggressor scorpions, 216 (20.2%) were black and 718 (67.3%) were yellow. In 133 of the cases (12.5%), color diagnosis of the scorpions involved could not be made by the individuals. Maximum of the patients occurred in the summer duration (35.3%), with the monthly distributions being August (12.5%), June (12.3%), September (12.2%) and May (12%). A smaller number of the patients were seen in January (1.9%), February (1.9%) and March (2.2%).

Table 3. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by scorpion body color in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006 -2008).

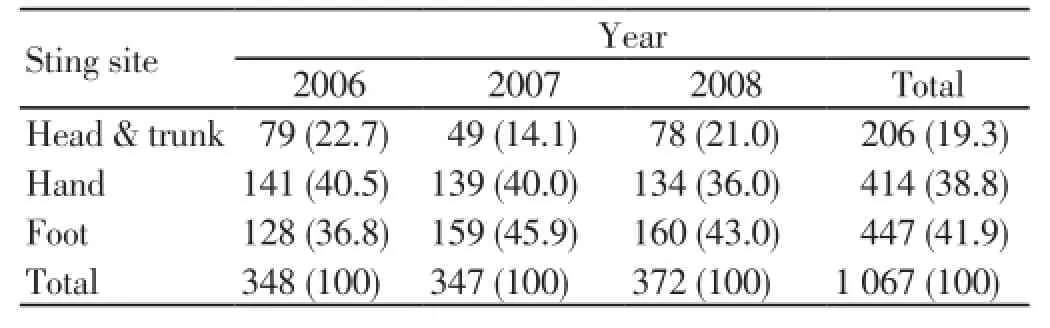

The frequency of scorpion stings in this study regarding to 2006-2008 according to the season/year are displayed in the Table 4 and according to the months in the Table 5. About 15.6% of the cases arrived at the hospital after more than six hours (Table 6). The distribution of the sting sites are given in Table 7 (41.9% for lower extremities and 38.8% for upper extremities). During this study, out of 1 067 patients, 4.5% (n=48) had sting scorpion history (Table 8). Results of our research according to history of receiving the antivenin are shown in the Table 9.

Table 4. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by season in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006 -2008).

Table 5. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by month in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006-2008).

Table 6. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by interval between sting and antivenin injection in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006-2008).

Table 7. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by sting site in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006 -2008).

Table 8. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by sting scorpion history in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006-2008).

Table 9. Distribution of scorpion sting cases by history of receiving antivenin in Gotvand County, SW Iran (during 2006-2008).

4. Discussion

About 1 500 species of scorpions are reported. Nearly thirty of them are known as potentially hazardous for individuals[3,14]. Approximately 94 percent of the scorpion stings happen the nighttime and indoors particularly in villages. Almost 88 percent of the accidents do not need any hospitalization[21,22]. Climatic conditions such as, heat and drought are significant risk factors[23].

Adults and among them men are mostly stung by scorpions. Nevertheless, envenomations are more intense in children in whom fatality is significantly greater than in adults[22,24]. We ascribe this great incidence of accidents among men to their greater curious nature and risk-taking treatment, like wearing shoes and clothes and picking up stones without searching for the attendance of scorpions. A total of 1 067 patients were reported during the three year period. In our study, of victims, 51.8% were males. In Turkey study females were more frequently stung by scorpions[1]. Pardal reported the most (83.3%) of cases as male in Brazil[25]. It was reported in two different researches made in USA and Australia that the women were stung more than the men[26,27].

In kassiri’s study, most of the patients were female (57.6%) and 42.4% were male[28]. Different studies have shown varied gender distribution for scorpion stings. In the current study, the stings mainly occurred in urban areas (55.9%) than rural areas (44.1%). In Ulug’s research in Turkey, 73.7% of stings were reported from rural areas which is similar to our study[4].

On the other hand, in the county of Baghmalek, Iran, approximately 64.8% stung cases were found in villages[29]. The results of Pipelzadeh’s research over five years among humans stung byH. lepturusshowed that 43% of individuals were from rural regions[15]. In Rafizadeh’s survey on scorpionism in Iran, stings occurred mainly in rural regions (57.7%)[17].

In our study, of offender scorpions, 20.2% were black and 63.3% were yellow. In the study of Dezful County, Iran, frequencies of most prevalent scorpions that stung the cases were 67.2%, 14.8% and 18% for yellow, black and other scorpions, respectively[30]. In Turkey’s investigation on 120 scorpion-stung cases reported 71.7% black scorpions and 28.3% yellow scorpions[1].

In a five year epidemiologic study on patients in Ramhormoz County, Iran, revealed that 52.7% and 19.7% were injured by yellow and black scorpions, respectively[10]. In an investigation in Saudi Arabia, of offender scorpions, 49% were black and 38% were yellow[31]. In Ulug’s study, 61.6% of the scorpion stings were caused by black scorpions and 17.2% by yellow scorpions[4].

Talebian reported that in Kashan County, Iran, black species were the most prevalent reported scorpions (34.9%); however, 19.6% patients were stung by yellow species and 45.5% of the patients failed to indicate the liable scorpion[32]. In a research on 12 150 cases, the scorpions responsible for the most of stings in Khuzestan Province were reportedd as 17.4% black (Androctonus crassicaudaandHottentotta schach), 53.3% yellow (Mesobuthus eupeus,Hottentotta saulcyi,Odonthobuthus doriaeandHemiscorpius lepturus), and 29.3% unclear colors[33].

The present study shows that scorpion stings are frequent during the summer months. This result is in agreement with that of previous studies in Ramhormoz County, Kashan County, the southeast Anatolia region of Turkey (Mardin, Midyat) and Fez (Morocco) that have reported 43.63%, 60.8%, 71.7% and 94.4% of scorpion sting cases occurred during the hot season of the year, respectively[4,10,32,34]. In Brazil, the largest number of stings observed during hot and wet months[35].

These changes may reflect variations in environmental situations, particularly an arid or rainy summer season. In our study the frequency of stings was determined 80.7% in feet and hands that was clearly various from those in other parts of the body. This result is not very various from those found by other researchers who displayed that feet and hands were more frequently stung than other body parts[1,4,15,17,28-30,33].

In the current investigation, 84.4% of the victims entered at the hospital for antivenin injection in less than six hours after their accidents. In Ulug’s study, the mean time passed between scorpion sting and entrance to the hospital was (1.5±1.1) h (range: 0.5-6.0 h)[4]. In Abourazzak’survey, about 32.5% of the patients got at the hospital more than four hours after their events[34].

This is the first epidemiologic investigation associated with scorpion stings in Gotvand County, as far as we know. Males and the people in the urban areas were more frequently stung by scorpions. Furthermore, extremities were the most prevalent source that was stung by scorpions. This epidemiologic data are useful for prevention of scorpion stings and health education. Moreover, early treatment is especially important for patients.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to staffs of Gotvand health services centers for their contribution and help. We also thank Miss Pargol Jahfar-Kharati and Mr. Javad Shamsi from Gotvand health services center for their support. This research was supported by the project No. 88S.101 Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical sciences Vice-Chancellor for Research affairs.

[1] AI B, Yılmaz DA, Sogut O, Murat Orak M, Ustundag M, Bokurt S. Epidemiological, clinical characteristics and outcome of scorpion envenomation in Batman, Turkey: An analysis of 120 cases. Akademik Acil Tip Dergisi 2009; 8(3): 9-14.

[2] Devaux C, Jouirou B, Krifi MN, Clot-Faybesse O, El Ayeb M, Rochat H. Quantitative variability in the biodistribution and in toxicocinetic studies of the three main alpha toxins from the Androctonus australis hector scorpion venom. Toxicon 2004; 41: 661-669.

[3] Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: A global appraisal. Acta Tropica 2008; 107: 71-79.

[4] Uluğ M, Yaman Y, Yapıcı F, Can-Uluğ N. Scorpion envenomation in children: an analysis of 99 cases. Turkish J Pediatrics 2012; 54: 119-127.

[5] Krishnan A, Sonawane RV, Karnad DR. Captopril in the treatment of cardiovascular manifestations of Indian red scorpion (Mesobuthus Tamulus Concanesis Pocock) envenomation. J Assoc Physicians Ind 2007; 55: 22-26.

[6] Boşnak M, Ece A, Yolbaş İ, Boşnak V, Kaplan M, Gürkan F. Scorpion sting envenomation in children in southeast Turkey. Wilderness Environ Med 2009; 20: 118-124.

[7] Dehghani R, Fathi B. Scorpion sting in Iran: A review. Toxicon 2012; 60: 919-933.

[8] Zare-Mirakabadi A, Khatoonabadi SM, Teimoorzadeh S. Antivenom injection time related effects of Hemiscorpius lepturus scorpion envenomation in rabbits. Arch Razi Inst 2011; 66: 139-145.

[9] Zayerzadeh E, Zare- Mirakabadi A, Koohi MK. Biochemical and histopathological study of Mesobuthus eupeus scorpionvenom in the experimental rabbits. Arch Razi Inst 2011; 66: 133-138.

[10] Karami Kh, Vazirianzadeh B, Mashhadi E, Hossienzadeh M, Moravvej SA. A five year epidemiologic study on scorpion stings in Ramhormoz, South-West of Iran. Pakistan J Zool 2013; 45(2): 469-474.

[11] Navidpour S. Description study of Compsobuthus (Vachon, 1949) species in South and Southwestern Iran (Scorpiones: Buthidae). Archives Razi Institute 2008; 63(1): 29-37.

[12] Navidpour SF, Kovarík ME, Soleglad-Fet V. Scorpions of Iran (Arachnida, Scorpiones). Part 1. Khuzestan province. Euscorpius 2008; 65: 1-41.

[13] Dehghani R, Khamehchian T. Scrotum injury by scorpion sting. Iranian J Arthropod-Borne Dis 2008; 2(1): 49-52.

[14] Prendini L, Wheeler WC. Scorpion higher phylogeny and classification, taxonomic anarchy, and standards for peer review in online publishing. Cladistics 2005; 21: 446-494.

[15] Pipelzadeha MH, Jalalib A, Taraz M, Pourabbasb R, Zaremirakabadi A. An epidemiological and a clinical study on scorpionism by the Iranian scorpion Hemiscorpius lepturus. Toxicon 2007; 50: 984-992.

[16] Azhang N, Moghisi AR. Surveying of scorpion sting and snake bite during 2001-2005. Report of Center of Management of Preventing and Fighting with the Diseases 2006: pp. 1-29. (In persian).

[17] Rafizadeh S, Rafinejad J, Rassi Y. Epidemiology of scorpionism in Iran during 2009. J Arthropod-Borne Dis 2013; 7(1): 66-70.

[18] Dehghani R, Dinparast- Djadid N, Shahbazzadeh D, Bigdelli Sh. Introducing Compsobuthus matthiesseni (Birula, 1905) scorpion as one of the major stinging scorpions in Khuzestan, Iran. Toxicon 2009; 54: 272-275.

[19] Jalali A, Pipelzadeh MH, Sayedian R, Rowan EG. A review of epidemiological, clinical and in vitro physiological studies of envenomation by the scorpion Hemiscorpius lepturus (Hemiscorpiidae) in Iran. Toxicon 2010; 55: 173-179.

[20] Radmanesh M. Cutaneous manifestations of Hemiscorpius lepturus sting: a clinical study. Int J Dermatol 1998; 37: 500-507.

[21] Forrester MB, Stanley SK. Epidemiology of scorpion envenomations in Texas. Vet Hum Toxicol 2004; 46: 219-221.

[22] Celis A, Gaxiola-Robles R, Sevilla-Godinez E, de Orozco Valerio MJ, Armas J. Tendencia de la mortalidad por picaduras de alacran en Mexico, 1979-2003. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2007; 6: 373-380.

[23] Chowell G, Hyman JM, Diaz-Duenas P, Hengartner NW. Predicting scorpion sting incidence in an endemic region using climatological variables. Int J Environ Health Res 2005; 15: 425-435.

[24] Sofer S, Shahak E, Slonim A, Gueron M. Myocardial injury without heart failure following envenomation by scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus in children. Toxicon 1991; 29: 382-385.

[25] Pardal PP, Castro LC, Jennings E, Pardal JS, Monteiro MR. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of scorpion envenomation in the region of Santarem, Para. Brazil Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2003; 36: 349-353.

[26] Isbister GK, Volschenk ES, Balit CR, Harvey MS. Australian scorpion stings: a prospective study of definite stings. Toxicon 2003; 41: 877-883.

[27] Forrester MB, Stanley SK, Epidemiology of scorpion envenomations in Texas. Vet Hum Toxicol 2004; 46: 219-221.

[28] Kassiri H, Teimouri A, Shemshad M, Sharifinia N, Shemshad Kh. Epidemiological survey and clinical presentation on scorpionism in South-West of Iran. Middle-East J Sci Res 2012; 12(3): 325-330.

[29] Kassiri H, Shemshad Kh, Kassiri A, Shemshad M, Valipor AA, Teimori A. Epidemiological and climatological factors influencing on scorpion envenoming in Baghmalek County, Iran. Acad J Entomol 2013; 6(2): 47-54.

[30] Kassiri H, Mohammadzadeh-Mahijan N, Hasanvand Z, Shemshad M, Shemshad Kh. Epidemiological survey on scorpion sting envenomation in South-West, Iran. Zahedan J Res Med Sci 2012; 14(8): 80-83.

[31] Jahan S, Al Saigul AM, Hamed SAR. Scorpion stings in Qassim, Saudi Arabia A 5-year surveillance report. Toxicon 2007; 50: 302-305.

[32] Talebian A, Doroodgar A. Epidemiologic study of scorpion sting in patients referring to Kashan medical centers during 1991-2002. Iranian J Clinic Infect Dis 2006; 1(4): 191-194.

[33] Shahbazzadeh D, Amirkhani A, Dinparast Djadid N, Bigdeli Sh, Akbari A, Ahari H, et al. Epidemiological and clinical survey of scorpionism in Khuzestan province, Iran (2003). Toxicon 2009; 53: 454-459.

[34] Abourazzak S, Achour S, El Arqam L, Atmani S, Chaouki S, Semlali I, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of scorpion stings in children in FEZ, MOROCCO. Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2009; 15(2): 256.

[35] Guerra CM, Carvalho LF, Colosimo EA, Freire HB. Analysis of variables related to fatal outcomes of scorpion envenomation in children and adolescents in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 2001 to 2005. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2008; 84: 509-515.

ment heading

10.1016/S2221-6189(14)60067-6

*Corresponding author: Hamid Kassiri, School of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

Tel: +986113738269

Fax: +986113738282

E-mail: Hamid.Kassiri@yahoo.com

Epidemiology

Incidence rate

Iran

Journal of Acute Disease2014年4期

Journal of Acute Disease2014年4期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Acute and sub-acute toxicity study of Clerodendrum inerme, Jasminum mesnyi Hance and Callistemon citrinus

- Different profiles of mental and physical health and stress hormone response in women victims of intimate partner violence

- Time-critical AMI Detection: A novel and fast technique using the 12-lead ECG

- The acute effect of the antioxidant drug “U-74389G” on red blood cells levels during hypoxia reoxygenation injury in rats

- Successful treatment of lower urinary tract obstruction with peritonealamniotic and vesicoamniotic shunting

- Simvastatin-induced Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis