炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染的分子流行特征

秦娟秀, 马硝惟, 戴颖欣, 王亚楠, 刘 倩, 李 敏

·论著·

炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染的分子流行特征

秦娟秀, 马硝惟, 戴颖欣, 王亚楠, 刘 倩, 李 敏

目的 初步研究上海仁济医院炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌的分子流行特征,为炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染的监控提供证据。方法 对2014年6月-2015年6月的222份炎症性肠病腹泻患者粪便标本进行艰难梭菌毒素检测和厌氧培养。采用多位点序列分型(MLST)进行分型,传统PCR方法检测其毒素基因,琼脂稀释法检测艰难梭菌体外药物敏感性,同时对炎症性肠病患者所在病房进行环境中艰难梭菌检测。结果 222份粪便标本中艰难梭菌的检出率为13.5 %(30/222),克罗恩病和溃疡性结肠炎患者中艰难梭菌检出率为15.7 %(22/140)和9.8 %(8/82),病房环境共检出4株艰难梭菌。MLST分型22株艰难梭菌为14种ST型,主要型别为ST54型。PCR检测毒素基因显示TcdA+TcdB+菌株为主(72.7 %,16/22),未检出二元毒素。22株艰难梭菌对氯霉素、四环素、氨苄西林、甲硝唑、万古霉素和美罗培南均敏感,对克林霉素耐药率较高,为63.6 %,8株对莫西沙星耐药。结论 炎症性肠病腹泻患者中艰难梭菌毒素基因以TcdA+TcdB+型为主,菌株克隆以ST54型为主,该型菌株在病房环境中也有检出。应当密切监测炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌的感染毒素基因。

艰难梭菌; 炎症性肠病; 药敏试验; 多位点序列分型; 毒力基因

艰难梭菌是革兰阳性有芽孢的厌氧菌,艰难梭菌毒素A和B是导致肠道炎症和组织病变的主要致病因子。艰难梭菌引起的感染可从轻微腹泻发展至假膜性肠炎甚至死亡。仅在美国,2009年艰难梭菌感染比2002年增长了237 %,每年因艰难梭菌感染治疗的支付大约1.2~3亿美元[1]。

炎症性肠病是病因尚不十分清楚的慢性非特异性肠道炎症性疾病,包括溃疡性结肠炎和克罗恩病。在中国地区,WANG等[2]将1989-2003年每5年划分为一个阶段,最后一个5年较第一个5年炎症性肠病的发病率增加了8.5倍。多篇文献证明炎症性肠病患者是艰难梭菌的易感人群,炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染的发病率较非炎症性肠病患者高且呈上升趋势[3-7]。因此探究炎症性肠病中艰难梭菌感染传播情况,尤其是分子流行特征,可以更好地为炎症性肠病患者艰难梭菌的感染监控提供参考。

1 材料与方法

1.1材料

1.1.1菌株来源 收集2014年6月-2015年6月的炎症性肠病腹泻患者粪便标本222份进行艰难梭菌筛查。腹泻的诊断标准为:每天大便次数≥3次,粪便性状异常,症状连续3 d,排除灌肠和泻药的使用。炎症性肠病的分类依据国际疾病分类第9版(ICD-9 555,556)[8],诊断标准参考文献[9]。本研究以患者出院诊断来确定疾病的分类,并依据患者的住院号进行查询统计患者年龄、性别、疾病等相关临床信息,并收集环境标本检测艰难梭菌。

1.1.2培养基和抗菌药物 艰难梭菌的选择性培养基为CDIF(法国生物梅里埃公司),Brucella琼脂培养基为美国BD公司生产,抗菌药物包括氯霉素、四环素、氨苄西林、莫西沙星、甲硝唑、万古霉素、克林霉素和美罗培南,来自美国Sigma公司。

1.1.3主要仪器与试剂 mini VIDAS仪器,法国生物梅里埃公司;PCR扩增仪,新加坡公司;基质辅助激光解析电离飞行时间质谱分析(MALDI TOF MS),德国BrukerDaltonik公司;PCR试剂盒和细菌基因组提取试剂盒,中国天根有限公司;毒素检测CDAB试剂盒,法国生物梅里埃公司;DNA Marker,日本TaKaRa公司。

1.2方法

1.2.1艰难梭菌的检测 对粪便标本同时进行VIDAS荧光酶联免疫技术检测A/B毒素,并将标本接种到CDIF进行选择性厌氧培养48 h。可疑菌落接种到Brucella血平皿(添加剂为5 mg/L血红素,1 mg/L维生素 K)进行纯分,采用MALDI-TOF MS对疑似菌株进行鉴定并同时保存菌株。环境中的艰难梭菌检测,用无菌棉签蘸取无菌生理盐水采集医务人员、患者、看护人员和运输人员的手以及病房的物品表面、厕所、门把手和地面标本,接种在CDIF平皿厌氧培养48 h,后续步骤同粪便标本中艰难梭菌的检测。

1.2.2核糖体分型(PCR ribotype)和多位点序列分型(MLST) PCR核糖体分型参照文献[10]方法进行。所得分型图谱以英文字母A、B、C、D等顺序进行分型。MLST参考网站http://pubmlst. org/cdiffi cile/,设计7对管家基因(adk,atpA,dxr, glyA, recA, sodA, tpi)设计引物(引物序列见表1),进行PCR检测。PCR产物送上海铂尚有限公司进行双向测序,测序结果在该网站进行比对[11]。并将7对管家基因拼接,利用MEGA.4建树,进行进化分析。

1.2.3毒素基因的检测 对tcdA和tcdB基因进行扩增,对毒素双阴性菌株利用Lok1/Lok3进行非产毒株的确认。引物序列见表1。同时检测二元毒素(ctdA和ctdB)。PCR扩增tcdA和tcdB基因的负调控基因tcdC并测序,检测是否有18 bp的缺失。

1.2.4药敏试验 参照CLSI推荐的琼脂稀释法测定8种药物的MIC[12]。将菌悬液调到107CFU/ mL,并取1 μL接种到Brucella血平皿(添加剂为5 mg/L血红素,1 mg/L维生素 K)。药敏试验结果参照CLSI 2015年标准判读。药物折点为:氯霉素≥32 mg/L; 氨苄西林≥2 mg/L;四环素≥16 mg/L;甲硝唑≥32 mg/L;莫西沙星≥8 mg/L;美罗培南≥16 mg/L;克林霉素≥8 mg/L。参照欧洲药物敏感性委员会(European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing ,EUCAST)标准,万古霉素的折点为≥2 mg/L.(clinicalbreak points-bacteria v6.0, http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/)

2 结果

2.1艰难梭菌检测

收集粪便标本222份,其中克罗恩病患者140份,溃疡性结肠炎患者82份;环境标本100份。粪便中艰难梭菌检出率为13.5 % (30/222)(艰难梭菌毒素检测阳性或培养出毒素阳性菌株),其中A/B毒素检测方法检出率为8.1 %(18/222),培养艰难梭菌22株,检出率为9.9 %(22/222)。克罗恩病患者中艰难梭菌检出率为15.7 %(22/140),溃疡性结肠炎患者中检出率为9.8 %(8/82)。培养方法比毒素检测方法检出率高,联合两种方法能提高艰难梭菌检出率。克罗恩病患者中艰难梭菌检出率较溃疡性结肠炎患者高。环境中共检测出4株艰难梭菌,均来自病房厕所。

表1 艰难梭菌MLST、核糖体分型和毒素检测的相关引物Table 1 Primers used for MLST, PCR ribotyping and detection of toxin genes

2.2基因分型

MLST结果显示:检出14种ST型,主要菌株为ST54型(5株),其次为ST2(2株)、ST35(2株)、 ST39 (2株)、ST98(2株)、ST37(1株)、ST139 (1株)、ST81(1株)、ST8 (1株)、ST14 (1株)、ST3(1株)、ST55(1株)、ST102(1株)和ST99(1株)。5株ST54菌株,均来自溃疡性结肠炎患者。在克罗恩病患者中艰难梭菌的ST型比较分散(图1)。环境中4株艰难梭菌,ST型为ST54、ST35、ST185和ST81。1株ST185未在患者中检出,其余3株均在患者中有检出。进化树显示:将菌株分为2部分:MLST Clade1和MLST Clade 4。核糖体分型将艰难梭菌分成7种型别(A、B、C、D、E、F和G)。其中核糖体A型包括ST2、ST3、ST14、ST185和ST102;B型对应ST98;C型对应ST8、ST55和ST99;D型对应ST35和ST135;E对应ST54;F对应ST81和ST37;G对应ST39。

图1 炎症性肠病患者和病房环境中感染艰难梭菌的进化分析Figure 1 Evolution of the Clostridium diffi cile strains isolated from patients with infl ammatory bowel disease and their environment

2.3毒素基因检测

检出的22株艰难梭菌中:TcdA+TcdB+型菌株16株(72.7 %),TcdA-TcdB+菌株4株(18.2 %)和TcdA-TcdB-菌株2株(9.1 %)。溃疡性结肠炎患者中8株艰难梭菌均为TcdA+TcdB+菌株;克罗恩病患者中14株艰难梭菌TcdA+TcdB+菌株8株(57.1 %),TcdA-TcdB+菌株4株(28.6 %),TcdATcdB-菌株2株(14.3 %)。TcdA+TcdB+的菌株以ST54/核糖体E为主,TcdA-TcdB+的菌株包括2株ST81和1株ST37,核糖体为F型。TcdA-TcdB-菌株2株则均为ST39/核糖体G型。所有菌株均未检出二元毒素,也未检出TcdC基因18 bp的缺失。

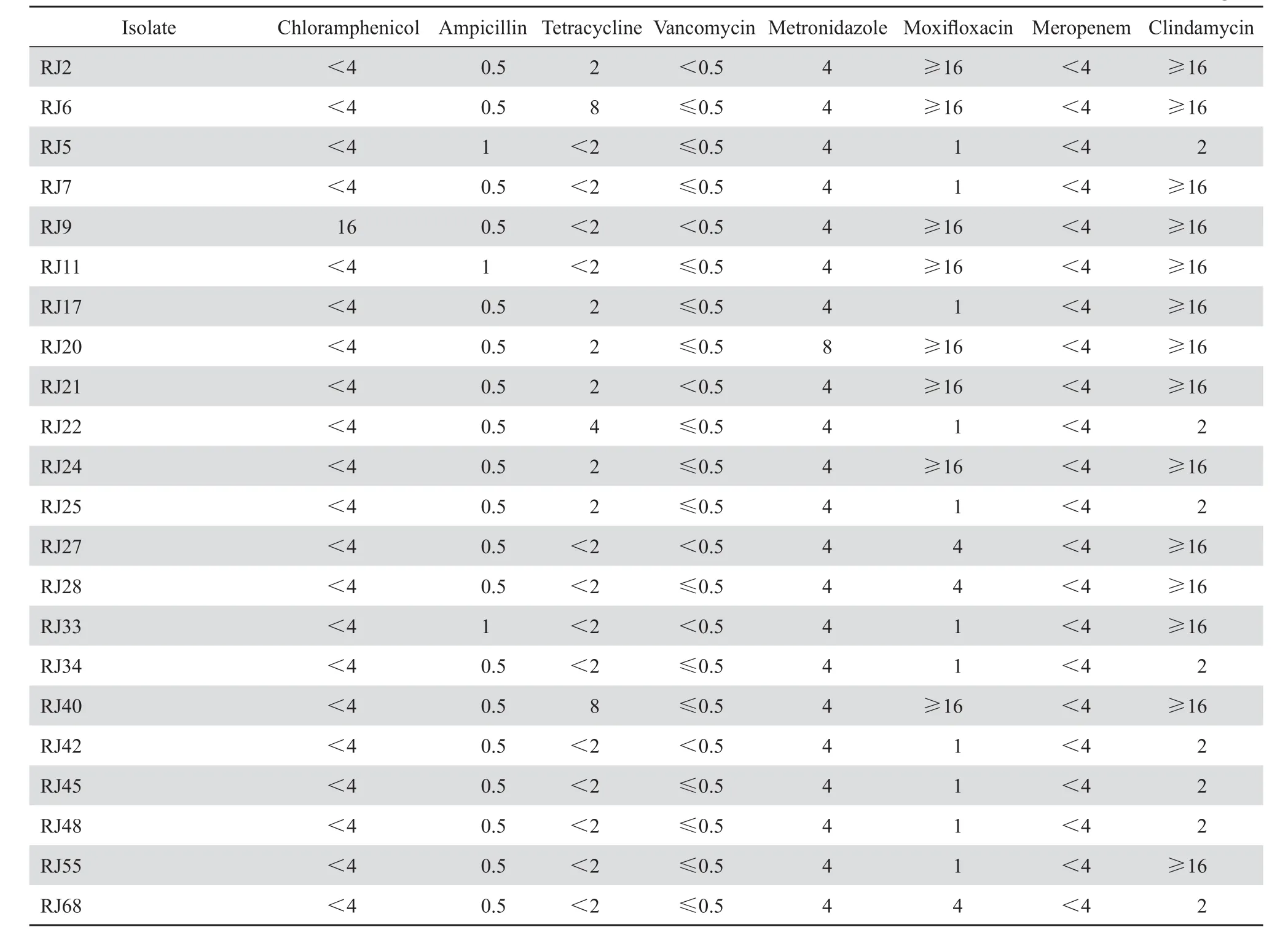

2.4药敏试验

炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌对克林霉素的耐药率较高,为63.6 %(14/22),8株艰难梭菌对莫西沙星耐药。所有菌株对氯霉素、四环素、氨苄西林、甲硝唑、万古霉素和美罗培南6种药物均敏感。结果见表2。

3 讨论

近年来,艰难梭菌的感染率和严重程度均呈不断上升趋势,炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌的感染率也呈现上升趋势。多篇文献报道炎症性肠病是艰难梭菌感染的危险因素,BOSSUYT等[13]发现炎症性肠病患者与非炎症性肠病患者相比,艰难梭菌的感染率高出3.75倍。KIM等[14]报道炎症性肠病患者多采用激素和免疫抑制剂治疗,肠道生理和解剖结构改变,明显增加了艰难梭菌感染的风险。

不同方法学对艰难梭菌的检出率不同,本次调查中我们采取了2种方法,VIDAS荧光酶联免疫技术检测A/B毒素和CDIF培养基选择性培养。后者的检出率较前者高(9.9 %对 8.1 %),联合两种方法可提高艰难梭菌的检出率(13.5 %),VIDAS检测毒素操作简单,结果较快,但灵敏度较低;培养方法操作较为复杂,培养后还需进行PCR鉴定毒素基因,周期较长,但该方法可用于艰难梭菌的分子特征研究。

表2 炎症性肠病患者感染的艰难梭菌药敏结果Table 2 Antibiotic resistance patterns in 22 C.diffi cile clinical isolates from patients with infl ammatory bowel disease(mg/L)

不同地区,不同病种患者艰难梭菌的感染率不同。近年来,国外报道炎症性肠病患者中的艰难梭菌感染发病率为1 %~28 %[3-6],来自美国、欧洲、日本和印度等国家文献证明溃疡性结肠炎患者相比克罗恩病患者更易患艰难梭菌感染[15-17]。国内仅李婷等[7]2013年报道的感染率为28.6 %(8/28);荀津等[18]报道2011年感染率为10.71 %(6/56),克罗恩病患者艰难梭菌感染的发病率较溃疡性结肠炎患者高。我院炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌的发病率为13.5 %,与国内外相比处于中间水平,克罗恩病患者的发病率高于溃疡性结肠炎患者(15.7 %对9.8 %),与荀津等报道的结果相符。相比于李婷等的28例样本,本组炎症性肠病的患者较多(222例),且克罗恩病患者比溃疡性结肠炎患者多,这可能是与其结果不同的原因。

不同地区艰难梭菌的流行克隆也不同。在美国和部分欧洲国家以RT027型艰难梭菌为主[19-20],在亚洲如日本、韩国、中国等,则以RT017为主[21]。RT027型艰难梭菌在中国少有报道[22]。本研究艰难梭菌主要流行菌株为ST54,且环境中也检测到ST54。ST54占国内孕妇感染艰难梭菌第二位[23],该型菌株在智利、日本、印度等地均有检出[24],也在斯洛文尼亚的5种动物(猪、狗、猫等)粪便中检出[25],说明该型菌株在世界广泛分布。

在病房厕所中检测出4株艰难梭菌,3株同时在炎症性肠病患者粪便中检出,仅有1株ST185未在患者中检出。主要流行菌株为ST54。艰难梭菌的传播途径为粪-口传播,且孢子是艰难梭菌长期存在于环境中并造成传播的重要因素。在病房厕所中检出,提示艰难梭菌通过粪便排出体外并以孢子形式存在环境中。虽然尚无法判断患者-环境-患者具体传播途径,但应该及时监测病房环境中的艰难梭菌,深入系统的研究,从而预防艰难梭菌的传播。本次调查只选取了炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染的腹泻病例,很难区分腹泻是艰难梭菌感染还是患者本身炎症性肠病活动引起,很多感染的炎性指标(白细胞、C反应蛋白等)在炎症性肠病活动期也会升高。因此需寻求区分两者的生物标志物从而为临床治疗提供理论依据。

总之,本院炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌感染发病率较高,以TcdA+TcdB+型的产毒菌株为主。流行的克隆菌株以ST54为主,其他型别散在分布。应及时监测炎症性肠病患者中艰难梭菌的感染。

[1] RUPNIK M, WILOX MH, GERDING DN. Clostridium diffi cile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis [J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2009 (7):526-536.

[2] WANG YF, OUYANG Q, HU RW. Progression of infl ammatory bowel disease in China[J]. J Dig Dis, 2010, 11(2):76-82.

[3] TRIFAN A, STANCIU C, STOICA O, et al. Impact of Clostridium difficile infection on inflammatory bowel disease outcome: a review[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(33):11736-11742.

[4] RICCIARDI R, OGILVIE JW JR, ROBERTS PL, et al. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile colitis in hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2009, 52(1): 40-45.

[5] NGUYEN GC, KAPLAN GG, HARRIS ML, et al. A national survey of the prevalence and impact of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2008, 103(6): 1443-1450.

[6] JEN MH, SAXENA S, BOTTLE A, et al. Increased health burden associated with Clostridium diffi cilediarrhoea in patients with infl ammatory bowel disease[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther,2011, 33(12): 1322-1331.

[7] 李婷,王红玲,夏冰,等. 艰难梭菌在炎症性肠病围手术期患者中的感染及其相关危险因素[J]. 中华试验外科杂志,2013,30(8):1751-1753.

[8] AXELRAD JE, SHAH BJ. Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease: a nursing-based quality improvement strategy[J]. J Healthc Qual, 2016, 38(5): 283-289.

[9] 欧阳钦,潘国宗,温忠慧,等. 对炎症性肠病诊断治疗规范的建议[J]. 中华消化杂志,2001,4(21):236-239.

[10] STUBBS SL, BRAZIER JS, O’NEILL GL, et al. PCR targeted to the 16-23 SrRNA gene intergenic spacer region of clostridium diffi cile and construction of a liabrary consisting of 116 different PCR ribotypes[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1999, 37(2):461-463.

[11] STABLER RA, DAWSON LF, VALIENTE E, et al. Macro and micro diversity of clostridium diffi cile isolates from diverse sources and geographical location[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3):e31559.

[12] Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria[S]. 8th ed. approved standard M11-A8. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2012.

[13] BOSSUYT P, VERHAEGEN J, VAN ASSCHE G, et al. Increasing incidence of Clostridium diffi cile-associated diarrhea in infl ammatory bowel disease[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2009, 3(1):4-7.

[14] KIM JH, MUDER RR. Clostridium diffi cile enteritis: a review and pooled analysis of the cases[J]. Anaerobe, 2011, 17(2):52-55.

[15] RODEMANN JF, DUBBERKE ER, RESKE KA, et al. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007, 5(3):339-344.

[16] KANEKO T, MATSUDA R, TAGURI M, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in patients with ulcerative colitis:investigations of risk factors and effi cacy of antibiotics for steroid refractory patients[J]. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol, 2011, 35(4): 315-320.

[17] KOCHHAR R, AYYAGARI A, GOENKA MK, et al. Role of infectious agents in exacerbations of ulcerative colitis in India. A study of Clostridium diffi cile[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 1993, 16(1): 26-30.

[18] 荀津,夏冰,彭谋,等. 炎症性肠病与艰难梭菌感染的相关性[J]. 武汉大学学报( 医学版),2012,33(5):680-683.

[19] HE M, MIYAJIMA F, ROBERTS P, et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium diffi cile[J]. Nat Genet, 2013, 45(1): 109-113.

[20] RILEY TV, THEAN S, HOOL G, et al. First Australian isolation of epidemic Clostridium diffi cile PCR ribotype 027[J]. Med J Aust, 2009, 190(12): 706-708.

[21] PUTSATHIT P, KIRATISIN P, NGAMWONGSATIT P, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Thailand[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2015, 45(1): 1-7.

[22] WANG P, ZHOU Y, WANG Z, et al. Identification of Clostridium difficileribotype 027 for the first time in mainland China[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2014, 35(1): 95-98.

[23] YE GY, LI N, CHEN YB, et al. Clostridium diffi cile carriage in healthy pregnant women in China[J]. Anaerobe, 2016, 37: 54-57.

[24] PLAZA-GARRIDO Á, BARRA-CARRASCO J, MACIAS JH,et al. Predominance of Clostridium diffi cile ribotypes 012, 027 and 046 in a university hospital in Chile, 2012[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2016,144(5): 976.

[25] JANEZIC S, ZIDARIC V, PARDON B, et al. International Clostridium diffi cile animal strain collection and large diversity of animal associated strains[J]. BMC Microbiol, 2014, 14:173.

Molecular epidemiological analysis of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with infl ammatory bowel disease

QIN Juanxiu, MA Xiaowei, DAI Yingxin, WANG Yanan, LIU Qian, LI Min. (Department of Clinical Laboratory, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200127, China)

Objective We evaluated the molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile strains in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in our hospital so as to provide evidence for effective surveillance of C. diffi cile infection. Methods From June 2014 to June 2015, a total of 222 stool samples were collected from inpatients with infl ammatory bowel disease and sent to clinical microbiological lab to test C. diffi cile by VIDAS fl uorescence enzyme immunoassay and culture. We analyzed the clonal relatedness of bacterial strains by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), antimicrobial resistance pattern by agar dilution method and prevalence of toxin genes by conventional PCR. Simultaneously, we also examined the environment of the ward where the patients stayed.

Results The C. diffi cile was identifi ed in 30 (13.5%) of the 222 patients. The incidence of C. diffi cile infection (CDI) was 15.7% (22/140) in patients with Crohn’s disease and 9.8% (8/82) in patients with ulcerative colitis. Four strains of C. diffi cile were isolated from the ward environment. All the 22 clinical strains from stool samples were typed into 14 STs by MLST analysis. The most common type was ST54 (5 strains). Most (72.7%) of the 22 strains belonged to toxin A+B+. However, no isolates contained binary toxin genes. Of the C. difficile strains evaluated, 63.6% displayed resistance to clindamycin and eight strains were resistant to moxifl oxacin. All the strains were susceptible to the other six drugs, i.e., chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ampicillin, metronidazole, vancomycin and meropenem. Conclusions Strains with toxin A+B+ were the most common C. diffi cile isolates. ST54 was the most predominant STs in patients with infl ammatory bowel disease in our hospital. It’s necessary to focus on the surveillance of C. diffi cile infection in patients with infl ammatory bowel disease.

Clostridium difficile; inflammatory bowel disease; antimicrobial susceptibility testing; multilocus sequence typing; virulence factor

R378.8

A

1009-7708 ( 2016 ) 06-0761-06

10.16718/j.1009-7708.2016.06.015

上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院检验科,上海 200127。

秦娟秀(1989—),女,硕士研究生,初级检验师,主要从事病原微生物的致病机制研究。

李敏,E-mail: ruth-limin@126.com。

2015-12-29

2016-03-06