Unlocking quality in endoscopic mucosal resection

Eoin Keating, Jan Leyden, Donal B O'Connor, Conor Lahiff

Eoin Keating, Jan Leyden, Conor Lahiff, Department of Gastroenterology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin 7, Ireland

Eoin Keating, Jan Leyden, Conor Lahiff, School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin 4, Ireland

Donal B O'Connor, Department of Surgery, Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin 24, Ireland

Donal B O'Connor, School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland

Abstract

A review of the development of the key performance metrics of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), learning from the experience of the establishment of widespread colonoscopy quality measurements. Potential future performance markers for both colonoscopy and EMR are also evaluated to ensure continued high quality performance is maintained with a focus service framework and predictors of patient outcome.

Key Words: Endoscopic mucosal resection; Colonoscopy; Quality in endoscopy; Advanced therapeutic endoscopy; Large non pedunculated colorectal polyps; Key performance indicators

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy has proven benefit in screening for colorectal cancer and pre-malignant polyps, as well as utility in symptomatic populations for the detection and management of significant non-malignant pathologies[1,2]. Providing access to high-quality colonoscopy is an ongoing challenge for health services internationally. Ensuring that colonoscopy is performed to an acceptable standard requires an open framework of assessment of service and endoscopist performance as well as feedback mechanisms and training supports to improve quality.

International guidelines recommend a range of key performance indicators (KPIs) for colonoscopy which are evidence based and aim to quality assure and standardise the delivery of colonoscopy to patients. Technological advances as well as adoption of KPI standards have resulted in consistent improvements in colonoscopy quality over time[3,4].

While quality assurance in colonoscopy has become part of routine clinical care and service development, equivalent quality assurance standards in therapeutic procedures have yet to be achieved.These procedures carry significantly increased risk of complications compared to diagnostic endoscopy.

The specialised field of Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) has developed to allow safe management of complex or large non-pedunculated colorectal polyps (LNPCPs), which traditionally required surgery. Originally pioneered by Japanese endoscopists in the 1990s to facilitate resection of early gastric cancers[5], EMR was subsequently demonstrated to be effective in all areas of the gastrointestinal tract. An initial review on the efficacy of EMR in all areas of the gastrointestinal tract was conducted by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) in 2008, followed by a second technical analysis in 2015[6,7]. The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) also produced an initial guideline in 2015 to assess colonic EMR performance in Western populations and was the first to establish recommended key performance indicators to assess EMR practitioners[8]. This was followed by European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommendations in 2017, which included a framework for referral practices, equipment and peri-procedural management, in addition to strategies to improve performance, minimise complications and reduce the risk of recurrence for LNPCPs[9].

Quality assurance for EMR remains a challenge in day-to-day practice and the organisation of services in most settings has yet to allow for a robust framework to develop in a similar manner to diagnostic colonoscopy. In this article we will review the evidence for established and aspirational colonoscopy KPIs as well as discussing quality assurance metrics for endoscopic resection of LNPCPs,and training considerations.

CURRENT QUALITY INDICATORS IN COLONOSCOPY

Caecal intubation rate

Successful colonoscopic evaluation for colorectal pathology must adequately survey all anatomical areas of the colon. As the anatomical endpoint of the colon, intubation of the caecum confirms that the colonoscope has successfully traversed the remainder the colon. Caecal intubation has been demonstrated to significantly affect the detection of proximal colorectal cancers[10,11].

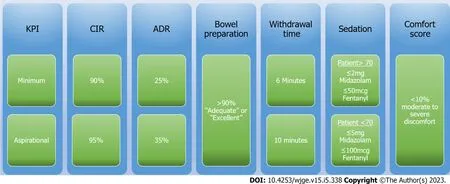

Current guidelines recommend a minimum caecal intubation rate (CIR) of greater than 90% for all intended full colonoscopies with an aspirational target of greater than 95%[12-14]. Caecal intubation is confirmed with the identification of the anatomical landmarks of the appendiceal orifice, tri-radiate fold and ileo-caecal valve. Photographic or video recording of these landmarks should be completed to document caecal intubation. Higher quality caecal landmark photographs, associated with higher quality endoscopy, have also been shown to have a higher polyp detection rate[15,16].

Adenoma detection rate

The adenoma detection rate (ADR) is defined as the proportion of patients where at least one adenoma is found among all patients examined by an endoscopist[14]. Higher ADR has an inverse relationship with interval colorectal cancer development[4,17]. ADR has thus been proposed as an important quality indicator for mucosal inspection[18].

While previous BSG guidelines had suggested a minimum ADR of 15% with an aspirational goal of 20%, the most recent 2021 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines have suggested a target minimum ADR of 30% with an aspirational target of 35%[12,13]. Similar ESGE guidelines have offered a minimum ADR target of 25%[14]. ADR amongst endoscopists is known to vary significantly with reported overall adenoma miss rates of 17% to 26%[19-22]. Corleyet al[17] demonstrated that achieving a 1% improvement in ADR correlates with a 3% decrease in the risk of post colonoscopy colorectal cancer. Therefore, strategies to even marginally improve ADR, particularly amongst endoscopists with lower ADRs, can potentially yield the greatest benefit for patients.

Adenoma rates are recognised to vary depending on patient demographics such as age and indication for colonoscopy[23]. Increasing age is consistently associated with increased adenoma occurrence,across all ethnicities, demonstrated in studies of black, Caucasian, Middle Eastern and Asian populations[23-26]. However adjustment to target ADRs is not generally required, but may be factored in to post-hoc reviews of endoscopist performance should this KPI fall short on an individual basis[27].

A concern has been raised at the potential for endoscopist manipulation of the binary mechanic of ADR through a “one and done” approach[28]. However, the prevalence of such behaviour was found to be infrequent and did not require a change to measuring ADR as a quality assurance indicator[29].Suggested alternative quality metrics such as adenoma per colonoscopy (APC), have been considered to improve reliability[30-33] and are reported in parallel with ADR routinely in endoscopic trials.

Bowel preparation

To confidently assess the bowel mucosa, adequate bowel cleansing is required. Polyethylene Glycol is the bowel cleansing regimen most commonly prescribed, formulated into a high (> 3 L) or low (< 3 L)volumes depending on patient factors such as fluid balance restrictions. Suboptimal bowel preparation is associated with lower ADRs and increased hospital costs[34,35]. Published rates of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy approach 25%[36]. The causes of poor bowel preparation are multifactorial and include age, educational level and sex, in addition to hospital inpatient colonoscopies[37]. Adequate bowel preparation, defined as the ability of an endoscopist to detect adenomas > 5 mm in size[38],requires patient understanding of and adherence to strict dietary and medication regimens for up to 24 hours prior to a colonoscopy. Timing of procedures to align with bowel preparation is another factor with same-day administration encouraged and colonoscopies ideally scheduled not more than 5 hours after commencement of the final sachet of preparation.

Strategies to improve dietary compliance, encourage patient education and medication tolerance have been trialled, leading to ESGE guidelines on recommended practice[37,39]. A recommended target of over 90% ‘adequate’ or ‘excellent’ bowel preparation has been proposed to be measured as a unit KPI[4,14].

Withdrawal time

Colonic mucosal inspection is primarily completed during colonoscope withdrawal post caecal intubation. The time allocated from caecal examination to removal of colonoscope from the rectum is recorded as the colonoscopy withdrawal time (CWT). CWT > 6 min is associated with a significant increase in ADR[19,40,41]. Conversely a CWT of < 6 min is linked to increased risk of interval colorectal cancer[42].

For expert endoscopists, defined as over 3000 procedures[19], the increase in ADR plateaus at a CWR of > 10 min[43]. For trainee endoscopists however, a CWT of greater than 10 min may be beneficial[44].Thus, the recommendation is for a minimum CWT of 6 minutes and an aspirational target of 10 min[12-14].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is likely to play a role here in the near future. The introduction of a CWT speedometer, warning endoscopists of rapid withdrawal, inserted into the overlay of the endoscopic image, was successful in significantly improving the ADR versus standard colonoscopy in a recent Chinese study (24.54%vs14.76%)[45].

Sedation

The majority of colonoscopies are completed using pharmacological sedatives. Standard practice targets conscious sedation achievedviaa combination of benzodiazepine (most commonly midazolam or diazepam) and opioid (most commonly fentanyl or pethidine) administration. Acceptable sedation targets require factoring in the patient age, in addition to co-morbidities. The BSG has a recommended sedation of ≤ 2 mg of midazolam (or equivalent) and ≤ 50 micrograms of fentanyl (or equivalent) in patients over the age of 70. In patients under 70, the recommended sedative dose is ≤ 5 mg of midazolam and ≤ 100 mcg of fentanyl[12]. The ASGE guidelines also recommend the use of a combination of opioid and benzodiazepine but do not specify a recommended dose[46].

These targets for sedation were included in the Performance Indicator of Colonic Intubation (PICI)study as a collective indicator of endoscopist performance[47]. This devised a binary outcome based on caecal intubation, patient comfort and sedation administered. Valoriet al[48] showed that a PICI positive colonoscopy was significantly associated with a higher polyp detection rate (PDR). However,the real world practice of sedation for colonoscopy has significant geographical variation and PICI outcomes may therefore be difficult to standardise internationally.

Rectal examination and rectal retroflexion

Digital rectal examination, or justification for omission is recommended in 100% of procedures by the BSG guidelines[12]. This prepares the anal canal for the entry of the colonoscope and may provide tactile information to the endoscopist of potential strictures or pathology which may impede colonoscope insertion.

Rectal retroflexion was demonstrated to be useful in the detection of low rectal pathology in the 1980s[49]. Consequently, it has been taught to all endoscopists and a target retroflexion rate of 90% has been proposed as a KPI[12]. However, the diagnostic yield of retroflexion has been demonstrated to be minimal[50,51]. Retroflexion can rarely cause perforation[52] and this needs to be considered in the context of patient factors.

Procedural volume

An acceptable minimum volume of procedures to achieve colonoscopy proficiency has been suggested at 200 procedures[12,53]. However studies on competency curves have identified a range from 233 to 500 procedures to achieve reliable CIR of > 90%[54-57]. This suggests that the currently accepted volume is slightly below the mean number of procedures required for colonoscopy training.

Similarly, the volume of procedures required to maintain competence has been recommended at 100 procedure per year but evidence suggests a higher target of 200 procedures per year is beneficial[58].Quality indicators including CIR and ADR are shown to be significantly associated with annual colonoscopy volume and would advocate for a higher competency maintenance target of 250 procedures[59].

Comfort scores

Recording of accurate comfort scores is essential to maintaining a patient centred service. Patients with positive experiences during colonoscopy are more likely to return and re-engage with services[60]. The accurate estimation of comfort scores is challenging due to the subjective nature of discomfort[61,62].Multiple endoscopic comfort-scoring systems are available. These include subjective reporting of discomfort (e.g.,Modified Gloucester Comfort Scale) and objective scales (e.g.,St Pauls Endoscopy Comfort Scale)[63,64]. Current BSG guidelines recommend frequent auditing of comfort scores in endoscopy and targeting < 10% moderate or severe discomfort in patients[12].

Comfort scores are recorded on the endoscopy reporting system and evidence suggests comfort scores are best provided by the endoscopy nurse. Inter-operator agreement on comfort scores is recognised to be inconsistent, particularly during periods of increased patient discomfort[65]. Nurse recorded comfort levels are strongly correlated with patient reported comfort scores[66].

Overall, endoscopists with lower average comfort scores have associated higher rates of CIR and lower sedation scores. Similarly, higher annual procedural volume are associated with lower comfort scores[66].

EMERGING QUALITY INDICATORS AND INTERVENTIONS IN COLONOSCOPY

Right colon retroflexion

Colonoscopy has been considered to be more effective at preventing left sided colorectal cancers than right sided cancers[67]. The higher rate of post colonoscopy colorectal cancers occurring in the right colon is thought to relate to missed adenomas at the index colonoscopy[68-70]. This has led to evaluation of strategies considered to enhance right colon visualisation.

Prolonged examination of the right colon may occur in anterograde view or in retroflexion. Both methods are demonstrated to increase the ADR[71,72]. Research into the use of RCR in increasing ADR significantly over multiple anterograde views has had mixed results[73-76]. Case studies have demonstrated that RCR can also be associated with colonic perforation[77]. In the absence of significant benefit over 2ndanterograde colonic intubation, RCR has not yet been recommended as a standard approach. Second look antegrade examination is favoured by many, with potential benefit using imageenhancement to support the second withdrawal[78].

MEDICATION ADJUNCTS

Anti-spasmodics

Anti-spasmodic agents such as hyoscine-n-butylbromide or glucagon are used by some endoscopists as smooth muscle relaxants to reduce mucosal folds and enhance colonic surface area exposure. Regular or intermittent usage of hyoscine during endoscopy as an has been reported by 86% of endoscopists in the United Kingdom[79].

Initial studies suggested that hyoscine use trends towards elevated ADR[80]. As such, it was included in the quality improvement in colonoscopy study bundle which showed a benefit when used with other adjuncts in colonoscopy[81,82]. Meta-analysis of the use of hyoscine in isolation however, has not been demonstrated to significantly affect the ADR[83-85]. Hyoscine is recognised to be associated with cardiac dysrhythmias and haemodynamic instability in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions such as heart failure and its use in these patients is cautioned against.

Simethicone

Simethicone is an emulsifying agent often used to clear bubbles in the gastrointestinal tract[86]. It can be incorporated into the pre-procedural bowel preparation to improve endoscopic visibility[87]. Preprocedural simethicone administration has shown mixed results on improving ADR[88-90].

Intra-procedural use of simethicone can result in suboptimal decontamination and[91]. Endoscope manufacturers have recommended against the use of intra-procedural simethicone[92]. Position statements from international endoscopic guidelines have cautioned against the intraprocedural use of simethicone whilst advocating for pre-procedural use[93,94].

Dynamic colonoscopy

Patient positional changes during colonoscopy, described as dynamic colonoscopy, refer to rotating the patient, from the left lateral position to a supine, right lateral or prone position intra-procedure. This is facilitated by the endoscopy nurse to ensure a safe positional change occurs. This is a cost neutral, safe and very quick technique, consistently associated with improved CIR, ADR and mucosal views[95-98].Barriers to positional changes during colonoscopy include patients with arthropathy, spinal injuries or external adjuncts such as percutaneous drains.

Dynamic colonoscopy is recognised to be an effective and achievable adjunct to colonoscopy. At present, it does not feature in endoscopist KPIs, likely due to inability to record and verify accurately.

Image definition and electronic chromoendoscopy

The image quality of modern colonoscopes has increased dramatically in recent years to incorporate the second generation high definition instruments available today. Magnification is now widely available and further enhances their diagnostic capability. Improved image quality from high definition colonoscopes has been proven to increase ADR[99-101] and also provides in advantages in other areas,including surveillance for Inflammatory Bowel Disease[102]. Virtual chromoendoscopy, such as the use of Narrow Band Imaging (NBI), facilitated by high definition colonoscopes has been shown in metaanalysis to improve ADR[78]. Similar to NBI, blue laser imaging and i-scan have been shown to improve ADR when compared to white light imaging[103-105].

DEVICE ASSISTED COLONOSCOPY

Cap assisted colonoscopy

Meta-analysis of CAC versus standard colonoscopy (SC) has demonstrated increased PDR and reduced procedural time[106,107]. CAC has been consistently to achieve higher ADR yieldsvsSC[108-110],although studies comparing CAC with cheaper adjuncts such as position changes or NBI are lacking. As in many areas of endoscopic research, further head-to-head trials of distal attachment devices would be welcome[111].

Endocuff assisted colonoscopy

While first generation Endocuff can be considered to have equivocal benefit in terms of ADR, with most advantages over SC relating to diminutive polyps, the second generation endocuff vision has shown benefit within screening populations. The well-conducted ADENOMA trial showed a significant improvement in ADR and MAP, without improved detection per unit withdrawal time, suggesting a value in supporting more efficient colonoscopy[112]. Cuff devices have also been shown to be superior to cap-assisted colonoscopy for ADR and lower adenoma miss rates and have particular utility in colon cancer screening[113,114].

MACHINE LEARNING/COMPUTER ASSISTED DIAGNOSTICS

Computer aided detection and computer aided diagnosis

Initial single centre trials of CADe have demonstrated positive results with reported increase in ADR with the addition of CADe[115]. However, the increased ADR was primarily due to the detection of non-advanced diminutive and hyperplastic polyps. Recent multi-centre studies indicated a significant improvement in APC and a non-significant trend towards greater ADR with the addition of CADevsstandard colonoscopy[116]. A potential adverse effect of CADe adoption will be the workload associated with diminutive and hyperplastic polyp assessment and removal[117], which can be offset by adoption of a resect and discard strategy, which has proven utility in the hands of specialist endoscopists using AI (CADx) support[118,119].

The ESGE comprehensively assessed both the potential benefits and concerns relating to AI In GI endoscopy and machine learning. Risk of external interference (hacking), endoscopist deskilling, overreliance on AI and the impact of biased datasets are all raised as concerns regarding AI adoption[120]and mitigation strategies will need to be incorporated as this field develops.

CURRENT QUALITY INDICATORS IN ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION

Recurrence/residual polyp evident at 12 months

EMR has been demonstrated to be a safe and effective alternative to surgery in the management of LNPCPs. However, early adenoma recurrence post EMR is recognised to occur in 15%-30% of patients[121,122] and necessitates a strict surveillance programme for early identification and resection of residual adenoma.

Recurrence rates are also shown to be dependent on the index resection method. En-bloc resections have a significant lower rate of adenoma recurrence compared to piecemeal[121]. Other factors with regard to recurrence rates include increased adenoma size[123], intra-procedural bleeding (IPB) at time of resection[123] and endoscopist experience[124]. Recurrence rates according to colonic location have demonstrated mixed results, with some studies indicating elevated recurrence rates in proximal locations[125,126], possibly reflecting increased resection difficulty in the right colon. Conversely, Limet al[127] indicated significantly higher recurrence rates in the distal colon and rectum.

Endoscopic thermal strategies such as snare-tip soft coagulation (STSC) have consistently demonstrated efficacy in reducing adenoma recurrence after piecemeal EMR (5.2%vs21%)[128] and (12%vs30%)[129]. Safety data from these analyses did not demonstrate any additional adverse risks.

Recurrence analysis may need to consider the mode of initial resection, with different recurrence rates likely for conventional EMR when compared with other modalities such as underwater EMR[130] and cold piecemeal EMR[131], which is primarily employed for resection of sessile serrated lesions.

Acknowledging the high rates of adenoma recurrence post EMR emphasises the requirement for a reliable surveillance programme. Meta-analysis indicates that 90% of recurrence is detectable by site check colonoscopy 6 months post EMR procedure[121]. Prospective studies, similarly examining surveillance intervals have confirmed the optimal timing of initial surveillance to be 6 months post resection[132]. Recurrence detected at initial surveillance colonoscopy is most commonly unifocal and diminutive[123]. The vast majority of early detected recurrence is suitable for endoscopic management[123,133].

Consolidating the information above, the 2015 BSG guidelines agreed a KPI threshold for recurrence of < 10% at 12 months post EMR with an aspirational target of < 5%[8]. This acknowledges the occurrence of early recurrence which can be managed endoscopically, while also accounting for cases of“late recurrence”, not detected at the initial post-EMR surveillance colonoscopy.

Perforation rate

Standard colonoscopy and polypectomy confers an accepted perforation risk of 0.07%-0.19%[134,135].Although rare, colonic perforation carries a considerable morbidity and mortality burden[136].Perforation during EMR remains rare, but is higher than standard colonoscopy, and must be addressed specifically during the informed patient consent process. Perforation rates during EMR range from 0.3%-1.3%[7,137,138].

Recognition and early intervention in the management of colonic perforation is essential to optimise patient outcomes[135]. Swanet al[139] described routine close inspection of the mucosal defect to examine for deep muscle injury. The benefit of immediate recognition of a potential MP injury affords the opportunity to apply endoscopic therapies such as clip placement to close defects with a view to minimising further complications[140,141].

Consequently, the BSG workgroup adopted a minimum standard of < 2% perforation rate with an aspirational standard of < 0.5%[8].

Post procedural bleeding

The reported incidence of PPB ranges from 2.6%-9.7%[142] but is limited by a lack of consensus definition for PPB. 65% of PPB is apparent within 24 hours of EMR, increasing to 88% at 48 hours[143].Post procedural bleeding was defined by the BSG working group as rectal bleeding occurring up to 30 days post EMR and could be further subcategorised as minor/intermediate/major or fatal according to the severity. PPB is accepted to be the most common serious complication of EMR procedures and is differentiated from IPB which can be managed endoscopically at the time of EMR.

Risk factors to predict clinically significant PPB were examined by Metzet al[143] in 2011,demonstrating that proximal (right) colonic location compared to distal colon (11.3%vs3.5%) and antiplatelet therapy were significantly associated with increased risk of PPB.

Electrocautery at the time of EMR, has also been shown to affect the rates and timing of PPB. Higher rates of IPB is associated with the use of pure cutting current as demonstrated by Kimet al[144].Conversely, a pure coagulation current, with lower risk of intra-procedural bleeding, confers additional risk of delayed-bleeding and potentially also perforation due to transmitted deep thermal injury[145].The ESGE recommends the use of a blended coagulation/cutting diathermy current for EMR[9].

Heterogeneity amongst study outcomes on the benefit of prophylactic clipping (through the scope clips, TTSC) in preventing PPB led to a meta-analysis which indicated no significant benefit to additional clip placement on PPB rates[146]. Citing the low rate of PPB in the control group of this metaanalysis (2.7%), Albenizet al[142] conducted a RCT of prophylactic clipping in high risk lesions and demonstrated a non-significant trend towards less PPB. Further investigation by Pohlet alconfirmed that prophylactic clipping was beneficial for proximal, large lesions, especially in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications[147]. The ongoing use of prophylactic clips to prevent TTSC should be patient-specific with recent studies favouring efficacy in clipping to reduce risk of PPB in the right colon[148]. Cost-analysis in this area will by driven by the relative costs of TTSCs and hospital admission costs in different countries, with high levels of variability evident[149].

The ESGE guidelines do not recommend prophylactic clipping as standard post EMR management[9]. However, their guidelines do recognise the need for prophylactic clipping in a subset of high risk patients. A clinical predictive score, “clinically significant bleeding” (CSPEB) was developed by Bahinet al[150], finding lesions > 30 mm in size, proximal location and additional co-morbidities warranted consideration for prophylactic clipping.

With regard to PPB as a performance indicator, the BSG guidelines have set a minimum PPB rate of <5% to be analysed at both an endoscopist and unit level[8].

Time from diagnosis to referral for definitive therapy and definitive therapy itself

Recognising the high risk of potential malignant transformation of LNPCPs, a 28 day cut-off for referral for consideration for EMR has been proposed by the BSG guidelines[8]. This 28 day standard was proposed but no minimum proportional standard has been published or disseminated. There is limited published data indicating compliance with this KPI, making interpretation of its impact challenging. A recommended 56 day period was allocated from referral to definitive endoscopic therapy with no minimum standard suggested as yet.

Audit data on real world clinical practice achievement of these EMR guidelines is necessary to establish the feasibility of the 28 and 56 day rule, respectively.

Procedural volume - Minimum annual EMR volume

As discussed above, procedural volume and clinical exposure are recognised contributory factors in colonoscopy performance. Bowel cancer screening programmes require an annual minimum volume of 150 procedures to ensure competency standards are maintained[151,152] although based on evidence discussed above, this may be a conservative Figure 1. Reviewing available literature, an initial training volume of 50 EMRs to establish proficiency with a minimum annual volume of 30 procedures to maintain competency are suggested[153].

Figure 1 Algorithm for quality indicators in colonoscopy. KPI: Key performance indicators; CIR: Caecal intubation rate; ADR: Adenoma detection rate.

ADDITIONAL AND FUTURE QUALITY INDICATORS IN ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION

Lesion complexity

Traditionally polyp complexity has been inferred by size, conventionally > 20 mm. Recognising polyp complexity as multifactorial, Guptaet al[154] developed the Size-Morphology-Site-Access (SMSA) score.This score assigns each component a difficulty rating, forming a composite polyp score (SMSA Score),reflecting overall complexity and was evaluated by ESGE. Increased SMSA score accurately predicts recurrence, adverse events and incomplete resection[155]. We suggest that the SMSA score should be reported by all endoscopists when they encounter complex polyps, as they can be useful in planning resection approach, time slots for lists as well as predicting outcome.

Snare tip soft coagulation

STSC is a safe and effective procedural method in reducing recurrence post piecemeal EMR[128] and has been revalidated by a recent 2022 meta-analysis[156]. Due to the strong evidence in favour of STSC use, the majority of endoscopists now employ this method to minimise recurrence. Consequently, the recording of a unit STSC rate as a KPI should be considered.

Unit compliance with recommended site check surveillance intervals

A reliable surveillance programme is an essential component of an EMR service. Optimal surveillance intervals are established and discussed above but the proportion of patients who successfully complete timely surveillance can vary. Measuring the proportion of patients achieving site checks at appropriate intervals would underline adherence to surveillance programmes and support management of EMR recurrences. Based off the meta-analysis findings of Belderboset al[121] that 90% of recurrence is detectable at 6 months, we suggest an interval of less than 180 days from date of resection for first site check (SC1) and 18 months from index for SC2, provided SC1 is clear. We further suggest that recurrences should be managed appropriately and in this scenario the next SC interval should again be< 180 days.

Surgical referral rates and incomplete resection

EMR has less morbidity, lower complication rates and is associated with shorter hospital stays compared to surgical resection[157] for benign polyps. However, recognising that EMR may not be possible in a proportion of referred patients, measurement of surgical referral rates were recommended by the BSG guidelines in 2015[8]. This is another area which may benefit from accurate SMSA assessment at index referral. Similarly, the rate of incomplete resection and subsequent surgical referral are a necessary performance indicator of EMR quality. This metric needs to incorporate the complexity of EMRs undertaken and should be subject to regular audit.

CONCLUSION

The focus on gastrointestinal endoscopy quality assurance and improvement has led to the development of standardised colonoscopy key performance indicators such as caecal intubation rate and adenoma detection rates[158]. The rapid endorsement of KPIs by international endoscopy societies[159] led to the widespread adoption of these benchmarks. New candidates for colonoscopy KPIs have since emerged and the arrival of artificial intelligence to general colonoscopy practice is likely to influence the field over the coming years.

Today, colonoscopy KPIs are valuable to ensure adequate endoscopist performance, identify underperforming practitioners and to target training interventions. Colonoscopy KPI monitoring and awareness is now instituted from the beginning of endoscopy training and regular audits are completed to ensure unit performance is adequate.

However, the adoption and widespread acceptance of endoscopic performance metrics has not permeated equally through all fields of endoscopy. Guidelines examining performance in gastroscopy have been detailed but adherence to these KPIs is suboptimal[160,161]. Specifically with regard to advanced endoscopic procedures, although publications recommending minimum standard practices have been available since 2015 for EMR, there is yet to be a similar consensus push towards outcome monitoring.

One of the challenges to KPI implementation for EMR is the limitation of endoscopy reporting systems. Continuous monitoring of complex data and surveillance metrics requires significant resource and it is not yet clear how we might achieve this. The collation and review of complication and,recurrence rates as well as referral timelines requires significant time, adding to endoscopist workload.

Quality assurance in endoscopy will always require practitioner performance measurement through KPIs. Both patients and the endoscopy community have benefited from the introduction and participation in colonoscopy KPIs. Replicating these enhanced standards of performance measurement in therapeutic endoscopy is therefore a logical next step in the evolution of endoscopy.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Keating E designed and drafted the original manuscript and reviewed all subsequent and final drafts; Leyden J and O’Connor D reviewed the draft and final manuscripts; Lahiff C designed and reviewed the original manuscript; all subsequent drafts, including the final draft.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare no conflict of interests for this review article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Ireland

ORCID number:Eoin Keating 0000-0002-1466-8752.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:Irish Society of Gastroenterology.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Cai YX

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy2023年5期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy2023年5期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy的其它文章

- Recent advances in endoscopic management of gastric neoplasms

- Improving polyp detection at colonoscopy: Non-technological techniques

- Rectal neuroendocrine tumours and the role of emerging endoscopic techniques

- Effect of modified ShengYangYiwei decoction on painless gastroscopy and gastrointestinal and immune function in gastric cancer patients

- Expanding endoscopic boundaries: Endoscopic resection of large appendiceal orifice polyps with endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection

- Effect of music on colonoscopy performance: A propensity scorematched analysis