Knowledge, attitude, and practice of monitoring early gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection

Xiao-Yun Yang, Cong Wang, Yi-Ping Hong, Ting-Ting Zhu, Lu-Jia Qian, Yi-Bing Hu, Li-Hong Teng, Jin Ding

Abstract

Key Words: Attitudes; Endoscopic submucosal dissection; Gastric cancer; Knowledge; Practice; Recurrence

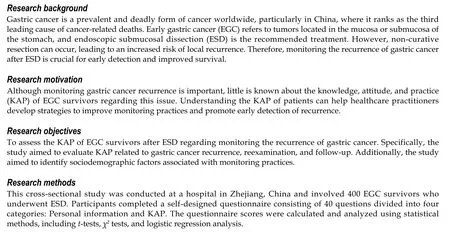

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths globally[1]. In China, gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with more than 500000 new cases expected in 2022[2]. Early gastric cancer (EGC) refers to cancers located in the mucosa or submucosa of the stomach regardless of local lymph node metastasis, with a better prognosis than advanced gastric cancer[3].

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is considered the first-line treatment for EGC regardless of its size or ulceration[4]. When compared to gastrectomy, ESD provides faster recovery, lower costs, and superior quality of life for patients with EGC. However, non-curative resection can occur after ESD and is strongly associated with the incidence of local recurrence resulting from incomplete resection, undifferentiated histology, a tumor-positive resection margin,lymphovascular invasion, or a depth of invasion greater than one-third of the submucosa[5]. In the 5 years following ESD, there is a cumulative incidence of 11.9% of local recurrences[6]. EGC survivors following ESD have a higher recurrence rate compared with those following gastrectomy[7]. A clinical application of the expanded criteria for ESD further increases the local recurrence rate of EGC[8,9]. Since early detection of recurrence improves survival for patients with gastric cancer[10,11], monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer after ESD is essential in patients as part of a surveillance strategy. However, little is known if patients understand the importance and how to monitor the recurrence of gastric cancer after ESD.

This is the first study to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer among EGC survivors after ESD in Zhejiang, China. We evaluated the KAP related to gastric cancer recurrence,reexamination, and follow-up. Furthermore, we examined sociodemographic factors associated with the practice of monitoring gastric cancer recurrence. The results may help medical practitioners improve the KAP of patients with EGC after ESD and facilitate early detection of gastric cancer recurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects

This cross-sectional study survey was conducted at the Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine between June 1, 2022 and October 1, 2022. The design phase started in June, focusing on feasibility and ethical considerations. Participants were recruited in July. Data collection and questionnaire surveys began in August. We conducted individual follow-ups and communicated with patientsviaphone calls. A total of 400 EGC survivors following ESD were recruited by phone. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinhua Hospital [Approval No. (2022)Lunshendi (211)]. All participants provided informed consent. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients underwent ESD for EGC at Jinhua Hospital; (2) Pathology after ESD revealed high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia,intramucosal carcinoma, or submucosal invasion < 500 µm; and (3) Participants were willing to take part in this study.The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients were unable to complete the questionnaire survey due to their inability to write or psychological diseases; and (2) Patients who underwent further gastric surgery.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was self-designed based on previous studies[12,13] and contained 40 questions in four categories in Chinese, including personal information (18 questions), knowledge (5 questions), attitude (6 questions), and practice (11 questions). The knowledge category scored 0-5 points, with 1 point awarded for each correct answer and 0 points for each wrong or unclear answer. The attitude category scored 6-30 points, with 5 points for a positive attitude and 1 point for a negative attitude. The practice category scores ranged from 0-11. Answers of “yes” were given 1 point, whereas answers of “no” were given 0 points. Cronbach’s α of the questionnaire was 0.841. Patients were recruited by telephone calls from the hospital. Patients who agreed to participate in this study were surveyed when they came to the hospital for follow-up.After the questionnaire survey was completed, investigators assessed the completeness, internal continuity, and rationality of the questionnaire. In cases where the questionnaire was incomplete, we contacted the patient by phone and,if necessary, assisted their family in answering it. Twenty-five patients did not come for follow-up. A cut-off point of at least 70% was used to categorize good knowledge, positive attitude, and good practice[14].

Sample size

Due to the lack of relevant literature, the sample size was calculated based on an anticipated proportion of 50% of ECG survivors engaging in monitoring EGC, with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error[15,16]. As a result, we determined that a sample size of 384 was required.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If conforming to the normal distribution, they were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between two groups using the Student’st-test. If not conforming to the normal distribution, they were expressed as medians (ranges) and compared between two groups using the Mann-WhitneyU-test. As for continuous variables among three or more groups, they were compared using the analysis of variance (a normal distribution with equal variance) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (skew distribution or unequal variance). Correlations were tested using Spearman’s test. Categorical variables were expressed asn(%). The influencing factors of proactive practice (categorized according to at least 70%) were explored using multivariate logistic regression.Variables withP< 0.05 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Two-sidedPvalues < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

RESULTS

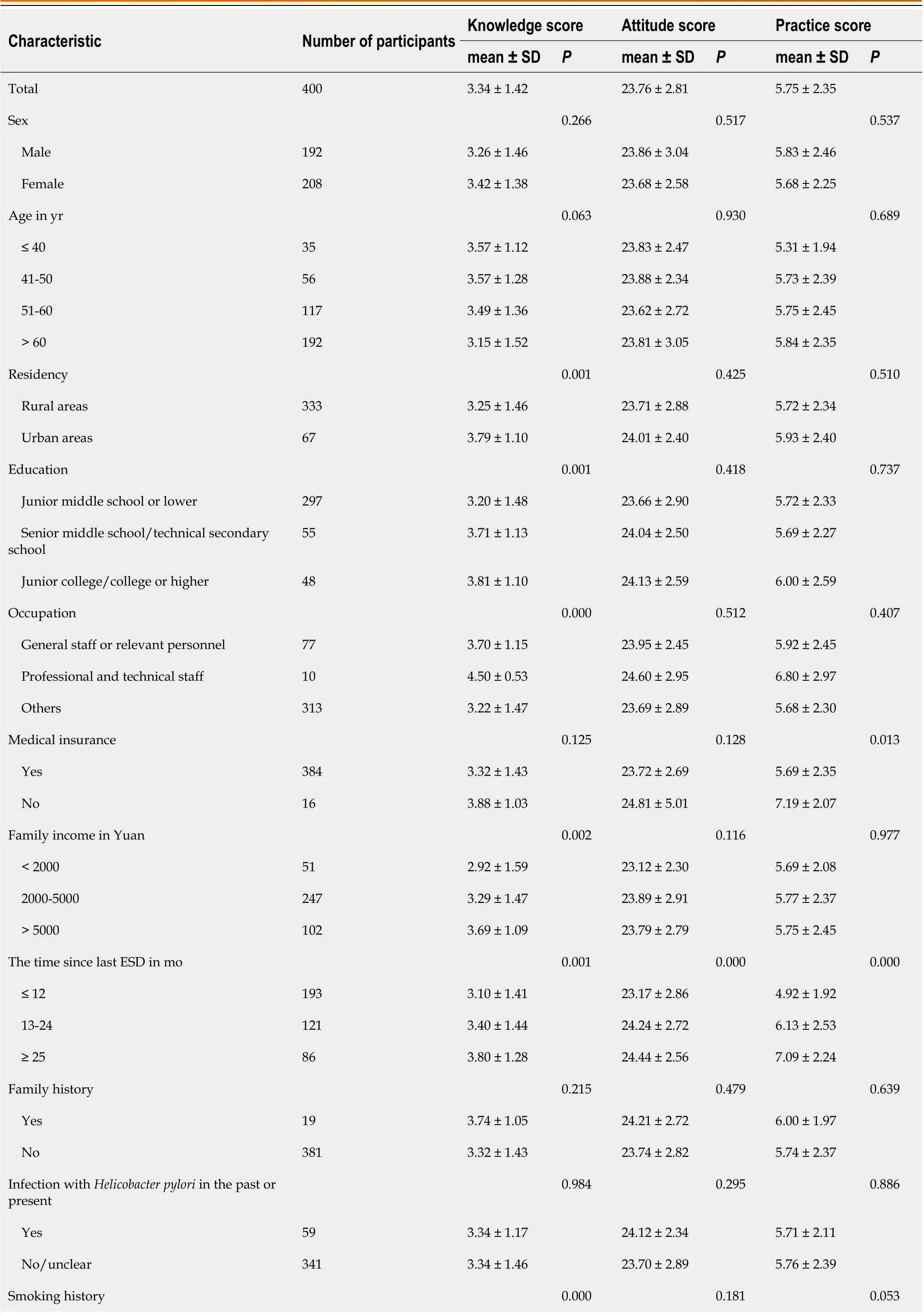

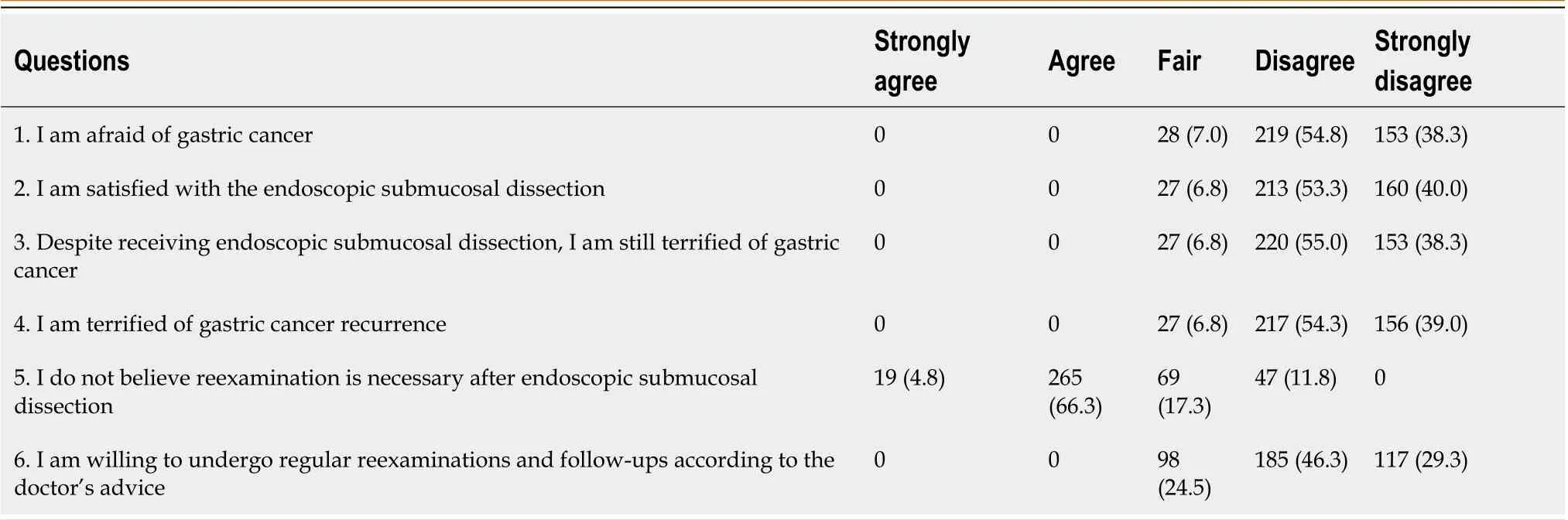

The KAP scores were 3.34 ± 1.42 (66.8%), 23.76 ± 2.81 (79.2%), and 5.75 ± 2.35 (52.3%), respectively (Table 1). Knowledge scores were significantly higher for participants from urban areas, with higher education levels, with professional or technical occupations, with higher family incomes, with a longer time since the last ESD, and without smoking or alcohol use history (allP< 0.05). The participants with a longer time since the last ESD and without alcohol drinking had significantly more positive attitudes regarding monitoring gastric cancer after ESD (bothP< 0.01). Compared to their counterparts, patients with medical insurance, with a longer time since their last ESD, and who did not smoke or drink alcohol were more likely to practice well in monitoring cancer recurrence after ESD (allP< 0.05). The distribution of knowledge scores showed that over 80.0% of patients were aware that follow-up, reexamination, and cessation of smoking and drinking alcohol following ESD are necessary, while less than 20.0% knew that gastric cancer will relapse after ESD (Figure 1). In the attitude assessment, 66.3% of participants believed that reexamination after ESD is not necessary, and none wanted to undergo regular follow-ups after ESD (Table 2). According to the practice assessment(Table 3), over 80.0% of patients followed a low-salt diet, stopped drinking alcohol, and took dietary supplements or Traditional Chinese Medicine after ESD. A surprising 96.5% of patients gained or lost more than 5 kg after ESD, with only 18.0% of them exercising regularly.

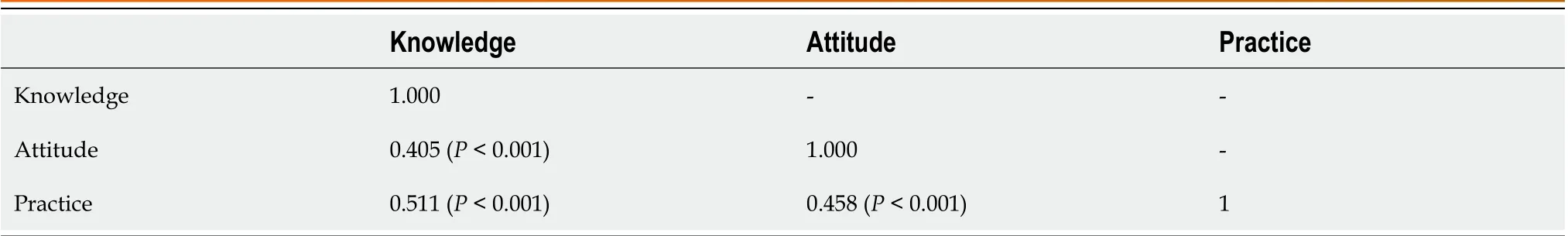

Table 4 shows significant positive correlations between knowledge-attitude, knowledge-practice, and attitude-practice,with correlation coefficients of 0.405, 0.511, and 0.458, respectively (allP< 0.0001). The multivariate analysis further revealed that knowledge scores [odds ratio (OR) = 1.916; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.424-2.578;P< 0.001], attitude scores (OR = 1.253; 95%CI: 1.124-1.396;P< 0.001), and the duration since the last ESD of 13-24 mo (vs≤ 12 mo since the last ESD; OR = 3.296; 95%CI: 1.761-6.172;P< 0.001) and ≥ 25 mo (vs≤ 12 mo since the last ESD; OR = 5.768; 95%CI: 2.963-11.226;P< 0.001) were independent predictors of proactive practice (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine KAP regarding monitoring of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD. In terms of monitoring gastric cancer recurrences after ESD, participants’ average KAP scores indicated inadequate knowledge, good attitude, and poor practice. Significant and positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitude, knowledge and practice, and attitude and practice. Sufficient knowledge, a positive attitude, and at least 12 mo since the last ESD were independent predictors for correct practice. The lack of knowledge and insufficient practice in monitoring cancer recurrence may explain 89.2% (43/400) of pathologically confirmed early tumors after ESD.

In our study, KAP scores were significantly higher among patients with a longer time since ESD, indicating that these patients have more time to gain knowledge and improve their attitude and practice related to monitoring cancerrecurrences. Cancer survivors with higher education and higher income were more likely to have the screening for second cancer or cancer recurrence[13]. In our study, in addition to the duration since the last ESD, residency, education,occupation, family income, and history of smoking or alcohol use were significantly associated with knowledge about monitoring cancer recurrences. Over 80% of the participants agreed that reexamination, follow-up, and quitting smoking and alcohol drinking are necessary after ESD. Surprisingly, less than 20% of participants correctly answered the question regarding the possibility of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD. Insufficient knowledge about cancer relapse may delay early detection of cancer recurrence, even if awareness may induce psychological stress that contributes to cancer incidence and progression[17]. Therefore, increasing awareness of cancer recurrence among EGC survivors is vital.

Table 1 Participant’ demographics and knowledge, attitude, and practice scores regarding gastric cancer recurrence after endoscopic submucosal dissection

ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; SD: Standard deviation.

Table 2 Questions and answers of attitude assessments, n (%)

Figure 1 Distribution of knowledge scores. K: Knowledge; K1: The gold standard for monitoring gastric cancer is gastroscopy; K2: Gastric cancer will not relapse after endoscopic submucosal dissection; K3: Follow up is still necessary after an operation; K4: It is not necessary to quit smoking or drink alcohol after surgery; K5: There is no need for reexamination after surgery. “1” indicates correct, while a “0” indicates wrong or unclear.

For patients with EGC after curative ESD, annual or biannual surveillance esophagogastroduodenoscopy and abdominal computed tomography are recommended for at least 5 years[18]. In spite of the fact that the majority of theparticipants were within 2 years of their last ESD, only 28.5% had yearly reexaminations by abdominal and chest computed tomography scans. It was interesting to note that over 80% of patients were aware of follow-up, reexamination,and cessation of smoking and drinking alcohol following an ESD. This paradox indicates that monitoring EGC recurrences after ESD requires putting knowledge into practice.

Table 4 Pearson correlation analysis between knowledge, attitude, and practice of monitoring gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection

Despite the overall unsatisfactory practice score, we noticed some highlights. After ESD, 83.5% of the participants followed a low-salt diet, and 84.3% of the participants quit smoking and drinking alcohol. These actions may reduce the risk of recurrence of gastric cancer since high salt intake, heavy smoking, and combined smoking and alcohol exposure are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer[19,20].

We noticed that higher knowledge and attitude scores were generally accompanied by increased practice scores.Pearson correlation analysis showed that knowledge-attitude, knowledge-practice, and attitude-practice were positively correlated, consistent with similar studies[21,22]. Moreover, multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that knowledge, attitude, and duration since the last ESD were independent predictors of practice. Therefore, providing patients with more time and improving their knowledge is a potentially effective way to promote practice in monitoring gastric cancer recurrence after ESD.

The discrepancy between a positive attitude, inadequate knowledge, and poor practice can be attributed to several factors. First, there may be a lack of awareness and education about the specific details and importance of post-ESD care.While participants may have positive attitudes based on a general understanding that monitoring is necessary, they lack in-depth knowledge about the specific actions required for effective monitoring and preventing cancer recurrence.Second, misconceptions or misunderstandings about post-ESD care may contribute to the disparity. Participants may hold positive attitudes but have incorrect beliefs or assumptions about the necessity of certain practices or the risks involved. Third, limited access to educational materials, healthcare professionals, and facilities providing post-ESD care,especially among participants from rural areas or lower socioeconomic backgrounds, can contribute to inadequateknowledge and poor practice. Furthermore, ineffective communication and a lack of clear instructions from healthcare providers can hinder the translation of positive attitudes into practical actions. Addressing these factors requires comprehensive efforts to facilitate the translation of positive attitudes into informed knowledge and effective practices.

Table 5 Influencing factors of proactive practice

CI: Confidence interval; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; F: Female; M: Male; OR: Odds ratio.

The KAP concerning the monitoring of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD holds significant clinical implications.Primarily, it identifies patient understanding, attitudes, and behavioral gaps that can be addressed to enhance patient outcomes and decrease recurrence rates. Furthermore, understanding the KAP of patients allows for a more personalized approach to patient education and intervention strategies, helping to bridge the gap between positive attitudes and effective practices, especially in areas like follow-up schedules and lifestyle adjustments. Lastly, studying KAP has essential implications for resource allocation and healthcare policy, as it underlines areas of need such as patient education, access to healthcare services, and efficient communication between healthcare providers and patients.

In this study, data were collected by self-reporting, which might be less reliable than medical records and laboratory measurements due to self-reporting bias. In addition, as this study was conducted in Zhejiang, China, the results do not reflect the KAP of monitoring cancer recurrence globally. To better understand the KAP of monitoring gastric cancer recurrence around the world, more studies in more areas with larger sample sizes are needed.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the KAP of monitoring gastric cancer recurrences after ESD was assessed for the first time in EGC survivors following ESD. Participants showed a positive attitude toward monitoring gastric cancer recurrence after ESD, but more efforts are needed to improve their knowledge and practice.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Yang XY carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript; Wang C, Hong YP,and Zhu TT proposed the questionnaire and revised it; Qian LJ was the pathologist who participated in collecting pathological data;Hong YP and Teng LH performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design; Ding J reviewed the literature and contributed to revising the article; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supported bythe Basic Public Welfare Research Program of Zhejiang Province, No. LGF19H160022; and the Key Project of Jinhua Social Development, No. 2018-3-001f.

Institutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinhua Hospital [Approval No.(2022) Lunshendi (211)].

Informed consent statement:All participants provided oral informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to report.

Data sharing statement:No additional data are available.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Xiao-Yun Yang 0000-0002-9164-5573; Cong Wang 0000-0003-1531-3176; Yi-Ping Hong 0000-0003-1043-7145; Ting-Ting Zhu 0000-0002-6068-1501; Lu-Jia Qian 0000-0001-8548-0717; Yi-Bing Hu 0000-0002-9821-6699; Li-Hong Teng 0000-0003-4439-1472; Jin Ding 0000-0003-0748-4362.

S-Editor:Chen YL

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Zhang XD

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年8期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年8期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Initial suction drainage decreases severe postoperative complications after pancreatic trauma: A cohort study

- Vascular complications of chronic pancreatitis and its management

- Historical changes in surgical strategy and complication management for hepatic cystic echinococcosis

- Post-transplant biliary complications using liver grafts from deceased donors older than 70 years:Retrospective case-control study

- Goldilocks principle of minimally invasive surgery for gastric subepithelial tumors

- Prognosis after splenectomy plus pericardial devascularization vs transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for esophagogastric variceal bleeding