全球本土化建筑:定义当代马来西亚身份认同的另一种方式

维罗妮卡·吴,牛颜秀 徐知兰

事实是:每一种文化都不可能支持和承受世界文明的冲击。这就是矛盾:如何在进行现代化的同时,保存自己的根基?如何在唤起沉睡的古老文化的同时,进入世界文明?——保罗·利科[1]

保罗·利科在《历史与真理》(1961)中指出“本土化”与“全球化”的概念都具有独一无二的地位,它们在寻求民族国家身份的过程中逐渐发展。建筑学中有关身份认同的问题一直以来采用修辞隐喻的话语模式。自希腊和罗马时代以来,建筑学的语言一直以风格和潮流来划分类别,如希腊建筑、罗曼建筑、巴洛克建筑、洛可可建筑、哥特建筑、新古典主义建筑、现代建筑、后现代建筑与解构主义等。在西方学术背景中,这些风格术语一直为人们广泛使用,并常用于描述某一特定时代的主导风格。由于殖民地化、全球化和其他零散的经济、政治、社会、文化和技术对建筑产生的迥然不同的影响,这些西方建筑的风格在像马来西亚这样的亚洲国家建成环境的背景中显得尤为突出。

最近10年,马来西亚作为一个带有强烈后殖民地文明烙印的国家正在经历建筑表现手法的范式转变。除了全球关注的可持续发展之外,寻求身份认同也仍是建筑学的推动因素。与所有其他的建筑学手法一起产生的,还有一种地域性的独特设计方法,它更倾向于体现马来西亚本土的身份认同感。地域性的设计思想不仅没有抛弃现代主义和历史设计的思想,并且还关注能在地理、历史、社会和文化层面、在任何特定地点产生影响的建筑学探索。

在迅速全球化的世界里,任何有关建筑学的调查研究都将不可避免地走向对本土文化和环境的思考。在字面意义上,“地域”一词通常用于形容从自身场所产生出来的建筑。1980年代,西方建筑历史学家肯尼斯·弗兰姆普顿在与此稍有不同的层面上定义了地域的含义。弗兰姆普顿将“地域”的概念置于全球化背景下进行考量。通过引述阿尔瓦·阿尔托等建筑师的思想,弗兰姆普顿使亚历山大·楚尼斯和利恩·勒费夫尔的“批判性地域主义”观念大为流行。这种方法是指,在对建筑本土环境的前提作出回应的同时,依然采用最先锋派的现代主义设计手法。它以建筑学的方式,力求在全球化的建成环境中对“场所感”[2]和“身份认同”的问题做出回答。

这便导致了对包括“本土”的含义,以及它如何确立一种表现地域或场所特征的建筑学方法的反思。“全球本土化”[3]这一术语回避了关于将全球和本土作为两个本质上迥然不同的概念的争论,这个术语的产生(在社会学的意义上)限定了全球化趋势与本土化趋势之间复杂的相互影响。本土与全球之间的矛盾产生了另一种建筑学的语言,它既未抛弃现代主义的观念,也未陷入字面意义上对历史的回归。相反,由此产生了能够表现出弗兰姆普顿所谓“具有场所意识的诗意”[4]建筑的多种形式。这一概念推动了与感官相关、思想深刻的作品,包含并表达了本土文化的变化过程,推动环境的可持续发展,也加深了人们对周围世界的认识。在亚洲地区即可见到这种回归场所的思想。

在马来西亚,出现了一些有关全球-本土的辩证关系的线索,作为另一股建筑学思潮。本文试图简短回顾这些全球-本土(“全球本土化”)的建筑,正是它们产生了目前具有场所意识的另一种设计方法。这种方法使本土建筑与西方建筑设计思想及理论并行无碍,并且暗示了设计思想和当代建筑思想的根基在于,在突出强调本土场所意识的同时,仍包含西方现代建筑的理论与思想。

本土特征作为灵感来源

语境的重要性,尤其是本土语境的重要性,已经成为西方建筑学话语模式中的隐喻。建筑理论家诺贝格-舒尔茨将“语境”一词形容为“地方特色”与日常生活中发生的现象,同时也指景观和城市所在的社会环境。通过引用苏珊·朗格(美国符号论美学家)的思想,诺贝格-舒尔茨提出“建筑学属于诗歌的范畴,其目的是帮助人们诗意地栖居”。然而建筑学是一门艰难的艺术。建造实用的城镇和建筑仍不足以构成建筑。只有当“全部环境变得清晰可见”[5]时,建筑才得以诞生。卡斯腾·哈利斯也提出过与之类似的思想,他强调需要“发现邻里社区和地域的重要性……它们将明确展现出自身特点”[6]。

这些思想突出了通过营造特定场所来赋予环境以意义的重要性。只有围绕地段的物质和文化环境、精心设计建筑,才能产生真正度身定制的作品,让现有的建筑环境更为完善。如吴石山(Ng Sek San)设计的双文丹玻璃屋就得到了彼得·斯达伯利在澳洲新南威尔士天堂海滩设计的以色列住宅的启发。其灵感也同样来自附近的旗鱼海番村,只是村舍中的房屋不如玻璃屋的永久稳固。尽管选用不同材料,功能极简的设计思想也仍可使人联想起临时棚屋的本质。建筑设计有意使玻璃屋和土著居民的房屋一样能够轻易拆除和重建。

“诚实的”建筑

为了增强人人平等的观念,建筑强调造价应在人们可承受的范围之内。为了使建筑造价可以承受,它们必须是“诚实的”。然而,什么是“诚实的”建筑?有关马来西亚建筑诚实态度的主题,贯彻了阿道夫·路斯在20世纪宣布的现代主义思想“装饰即罪恶”,正是这一宣言响应了以使用材料的诚实原则为基础的建筑学基本道德标准。笼统地说,这一信条意味着两点:(1)不应以其他材料掩盖建筑结构;或者(2)建筑设计必须与当代精神一致。与之类似的诚实态度也反映在了马来西亚的建筑中,然而其方式却体现在建筑造价的可承受程度及建筑设计对当地环境材料的敏锐度方面。

这种诚实的原则之一就是以一种真实的方式利用当地资源,从而反映因地制宜的建筑设计。例如,使用当地能够找到的材料,使之成为在施工过程中可以使用的原料。这在C'Arch建筑事务所、Khoo Boon Siew、Juteras设计事务所合作的贝隆雨林度假村中就得到了体现。度假村以用从地段原有建筑中拯救下来的废砖砌成的“乱”墙为特色。并且,作为酒店室外设计主要特征的“小树”屏也用当地有利于可持续发展的快速生长的竹子制成[7]。

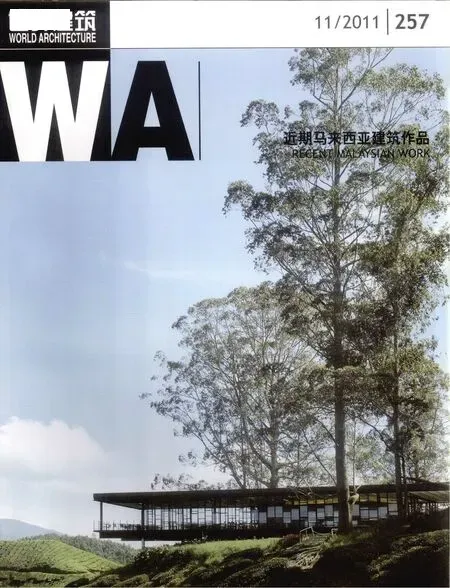

在地段上保留过去自然环境的思想也同样反映在了位于金马伦高原、由ZLG设计事务所设计的Boh茶园中:在大片的茶叶种植园景观上方,是茶园直线延伸的建筑形式,可谓密斯·凡·德·罗现代主义方形建筑的典范。为了利用地段周围凉爽的气候条件,钢框架的主入口立面以圆木间隔填充,而这些木材正是地段上原有的树木。设计者因为预算和地段位置所限而使用简单朴实且易于获得的材料,这一决策也让设计项目拥有了自己的特征和设计精髓[8]。

建构

使用材料的诚实态度产生了体现美感的建筑建构学:这种美感存在于材料组合之中,也存在于细节之中。这一理念在以弗兰姆普顿所述“建构”概念为基础的建筑中得到了体现,它关注建筑学作为建造技术和手艺的层面。设计策略的核心是将建造形式与材料特征视为不断深入发展的形式与空间表现手法中不可分割的一部分[9]。建筑作为手工业的思想又通过探索废旧材料和随手拾得的物件如何能够成为建筑原料的方式得到了进一步拓展,如Building Bloc建筑事务所在兰卡威设计的电线杆住宅。Building Bloc建筑事务所和Wen Hsia等建筑设计师,从吉打州、吉兰丹州和丁加奴州(马来西亚的东北部)的木料场回收到了那些电线杆。主结构框架和屋顶构架也都是从吉打州的一个木料场收集来的5×5见方的电线杆。旧木杆历经时间洗礼后呈现出美丽的色泽,在白蚁侵袭和风雨侵蚀的威胁下仍保持了一定的坚固程度。地板、墙板和屋瓦也都是从其他拆毁的建筑中抢救回来的。这座住宅的建构方式响应了密斯·凡·德·罗“上帝存在于细节之中”的格言。每根柱子都由固定在钢节点柱础上的4根5×5见方的木杆组成。柱础也能够起到隔绝白蚁的作用。住宅的主梁则由3根5×5的方木杆组成。它们有不同的截面,以墩接/嵌接方式连接。

对材料的敏锐感受也同样反映在建筑的地段特征方面。沿着槟榔屿的峇都丁宜沙滩的滨海地区坐落着由GDP建筑师事务所设计的龙柏酒店,其立面设计表现了各种石材的肌理与质感,并形成有呼吸感的建筑表皮。除了有助于自然通风之外,单体建筑的不同形式与它们的分布秩序在某种程度上也清晰地展现出建筑材料丰富多样的纹样图案,也没有对任何装修进行掩饰。这种方法重新肯定了原酒店的精神,即在60多年的时间内,这里建造了3组不同的建筑,形成了目前各种风格混杂的结果[10]。

乡土设计思想的当代阐释

马来西亚建筑将乡土设计原则融入设计之中。广义上说,乡土建筑指原始棚屋。在马来西亚,它通常指传统的马来屋。在凯文·罗设计的百叶窗盒住宅中,他将建筑抬升至与地面有些距离的柱桩上,以此处理有些设计难度的地形,从而无需进行土地平整。他由传统的Kampong村屋获得启发,让出建筑下方的地面作为景观使用。这块开敞的底层地面则为住宅提供了通风条件。双文丹的建筑也与此类似,建筑抬升离地,保护房屋免受打扰和其他因素的危害。传统马来屋的另一个本质特征是“会客空间”,即一种有遮蔽的单侧长廊,用于欢迎客人或与邻居闲聊。在石山建筑事务所设计的淡滨尼一道住宅中,住宅入口便引向一处有低矮木板平台的庭院。

同样,洛克-Wooi建筑事务所设计的建筑师Wooi自宅,则通过尝试重获建筑师本人在吉打州笨筒地区度过童年时光的核心精神,重新阐释了传统的马来屋。Wooi的自宅借用村屋的斜屋顶形式,安装了显眼的锌板伞状屋顶。墙面则由垂直放置的木条构成,以形成与通透可呼吸的村屋类似的空气流动效果[11]。

内外翻转:四墙之外的建筑

空间围合与建筑和自然的关系也是当代马来西亚建筑探索的主题。空间应该封闭在四墙一户之中吗?由于卫生观念的变化和新建筑材料(钢筋混凝土)技术的发明所定义的建筑空间,20世纪现代建筑因此瓦解了四墙一户的空间概念。将建筑空间打开,模糊室内外边界,这促进了自然与建筑之间的象征性关系。并且,西方关于建筑与自然辩证关系的思想在18和19世纪关于花园与乡村住宅的强调中也得到了描绘。源于阿卡迪亚景观透视法的建筑理想在艺术、建筑和文学中都有所体现。

在马来西亚的本土化语境中,建筑学探索了翻转建筑室内外特征的设计思想。在建筑室内外使用树木的方式,也使建筑得以生长。

在八打灵贸易中心(由来自小型项目事务所的凯文·马克·罗与作为当地设计协助单位的Yellil建筑事务所完成),尽管这是一处商业办公楼开发项目,墙面、地面和天花板也几乎都具有自然要素。

……优秀的建筑始于花园。——凯文·马克·罗[12]

穿过更为坚固厚重的混凝土通风砌块立面后,贸易中心出现一座花园庭院,人们能透过一个个办公室隔间的透明内墙看见这座花园。似乎,首先出现在这里的是树木,其次才产生了围合它们的墙体。层层挑空的平台突出了与通风砌块墙面相连的区域,诸多办公室在更高的楼层也拥有了花园空间。树木从地下车库向上生长,经过的每层楼面都呼应了大自然的力量[13]。罗相信,建筑应该与空间的开敞和建筑结构的非建筑化有关。他强调花园不仅仅是优秀建筑作品的点缀,并且,建筑中的非建筑元素也能够产生美感。

全球-本土的辩证关系为马来西亚产生另一种哲学思想和建筑实践铺平了道路。在反驳风格问题的过程中产生了马来西亚当代建筑的新方法,这种方法热情拥抱全球化的设计、传统的设计和本土的设计,并毫无芥蒂地同时接受所有这些观念。而当代建筑思潮和设计理念也并不是空穴来风。它们形成于某些哲学、经济、历史和社会文化影响的共同汇聚之处。尽管建筑的物质空间表现有所不同,其哲学核心仍植根于对因地制宜的建筑思想的关注,回归有关建筑经济、人文和场所的最本质基础。

建筑学关于身份认同的定义争论激烈。何谓身份?又是何者之身份?建筑学的话语模式经常需要面对有关身份认同的问题,就是因为身份认同是转瞬即逝的。因为身份认同由地点和时间所辖,而后两者从未保持不变。为了响应对“此地”与“此时”进行界定的独一无二的地位,全球语境与本土语境的意识也将继续在马来西亚当代建筑身份认同的定义与再定义中漫漫求索。然而,在这些当代建筑手法中,“全球本土化”必然占有一席之地。□

It is a fact: every culture cannot sustain and absorb the shock of modern civilisation. There is the paradox: how to become modern and to return to the sources; how to revive an old,dormant civilisation and take part in universal civilisation.——Paul Ricouer[1]

Paul Ricouer's words inthe History and Truth(1961) point out the unique position of both concepts of 'localness' and 'globalisation' has played out in seeking a national identity. The question of identity in architecture has been a rhetorical discourse. Since the Greek and Romans, the language of architecture has been classified based on styles and trends, for example Greek, Roman,Baroque, Rococo, Gothic, Neo-Classical, Modern,Post-modern and Deconstructivism amongst others.In the Western context, these styles have been widely used and often portrayed as the predominant style used for a specific era of time. Due to the disparate influence of colonialisation, globalisation and other discursive economical, political, social, cultural and technological influences on architecture, these Western styles are eminent amidst the backdrop of built environment in Asian countries such as Malaysia.

In the recent decade, Malaysia being a nation with a strong post-colonial culture is witnessing a paradigm shift in its architectural expressions. In addition to the global concerns of sustainability,the search for identity is still an impetus task for architecture. Amidst other architectural approaches,an alternative approach that is regionally specific emerges which has the propensity to portray a sense of Malaysian identity. While not rejecting modern and historical ideas, the regional ideas focus on architectural explorations that play out the effects of geography, history, society and culture in any one particular place.

In the rapidly globalising world, any investigation of architecture inevitably leads to considerations of local culture and environments. Taken literally, the term 'region' typically denotes architecture derived from its locale. In the 1980s, the architectural historian Kenneth Frampton in the West defined region in a slightly different perspective. Frampton viewed 'region' in a globalised context. Quoting architects such as Alvar Aalto, Frampton popularised Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre's concept of 'critical regionalism'. This approach refers to architecture that responds to its local premise yet in an avant-gardist, modernist approach. It is an approach to architecture that aims to respond to issues of 'placelessness'[2]and 'identity' within the globalised built environment.

This led to a rethink of what it means to be'local' and how it defines an architectural approach that portray the region or place. Avoiding the debates on the concepts of global and local as disparate ideas, the term 'glocalisation'[3]emerges(in sociology) defining a complex interaction between globalising and localising tendencies. The paradox between the local and the global defines an alternative language of architecture that does not reject modern ideas or lapsing into a literal return to history. Rather, a heterogeneous form of architecture that portrays what was termed by Frampton as 'a place-conscious poetic'[4]emerges.The concept fosters thoughtful works that engage the senses, embody and express local cultural processes, promote environmental sustainability,and enhance people's awareness of the world around them. Such returning to place ideas can be seen in the Asian region.

In Malaysia, traces of the global-local dialectic emerge as an alternative strand of thinking about architecture. This essay attempts to offer glimpses

of the character of the global-local ('glocal')architecture that produces the current alternative approach for place-conscious design. It draws parallels between local architecture and Western architectural ideas and theories, and suggests that the fundamental basis of contemporary architectural thinking emphasizes on the local sense of place while embracing theories and ideas of Western modernity.

Local character as inspirations

The importance of context, particularly local context, has been a rhetorical concern in the Western architectural discourse. This notion was described by the architectural theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz as'local character' and the phenomenon of everyday life as well as referring to landscapes and urban milieu.Quoting from Suzanne Langer, Norberg-Schulz argued that 'architecture belongs to poetry, and its purpose is to help man to dwell. But architecture is a difficult art. To make practical towns and buildings is not enough. Architecture comes into being when a 'total environment is made visible'[5]. Similar concerns were raised by Karsten Harries who stressed the need to 'discover the importance of neighborhoods and regions…which will articulate their character '[6].

These ideas emphasized the importance in making the environment meaningful through the creation of specific places. Architecture is carefully planned around the site's physical and cultural context to produce genuinely tailored made work that complements the existing context. For example, Ng Sek San's Sekeping Serendah Glass House is inspired by the small Peter Stuchbury designed Israel house in Paradise Beach, New South Wales. It is also inspired by the nearby Orang Asli village where their architecture is less permanent.Despite the difference in material, the essence of a temporary shelter is evoked as it is designed with only pure necessity in mind. The Glass House is intended to be demolished and rebuilt at ease similar to the aboriginal homes.

'Honest' Architecture

Reinforcing the idea that everyone is equal,architecture emphasizes on affordability. For architecture to be affordable, it has to be'honest'. But what does it mean for architecture to be 'honest'? The theme of honesty in Malaysian architecture carries through the 20th century modernist proclamation of Adolf Loos 'ornament is crime' echoing the basic moral values of architecture based on the principle of honesty of materials. Generally the term is used to mean one of two things: (1) the building does not cover up its structure and pretend to be something it is not;or, (2) the design of the building is coherent with the spirit of the modern age. Similar honesty is portrayed in Malaysian architecture but in a manner which reflects affordability and sensitivity of materials to its local context.

One principle of such honesty is the utilisation of local sources in a truthful manner to reflect a place-specific architecture. For example, the use of locally available materials that may have been made available during the construction works.This is demonstrated in Belum Rainforest Resort by C'Arch Architecture in collaboration with Khoo Boon Siew and Juteras which features the 'huruhara' wallsthat are constructed out of recycled bricks that were salvaged from the existing buildings on site. In addition, the 'sapling' screens that gives the resort its outdoor character is made of fast growing local timbers that are sustainable.[7]

1 文丹旗鱼海番村的典型村舍/Typical Orang Asli house found in Serendah

2 双文丹的玻璃屋/The Glass Shed of Sekeping Serendah

The idea of retaining the nature that once stood on site is also reflected in ZLG Design Boh Tea Centre,Cameron Highlands: the elongated rectilinear form of the Tea Center perch above the landscape of tea plantation exemplifying Mies van der Rohe's modern box architecture. Taking advantage of the cooling climate of the site, its front entrance facade is made of steel frames that are filled with timber logs of trees that once stood on site. The decision to utilize simple, humble and accessible materials due to budget and location constraint has given the project its signature and essence[8].

Tectonics

The honesty of materials results in architectural tectonic that portrays beauty: beauty in composition of materials and beauty in details. Such conception is manifested in architecture based on the notion of 'tectonics' as employed by Frampton which focused on architecture as a constructional craft[9].Design strategies centered on the philosophies of constructional form and material character as integral to an evolving architectural expression of form and space. The idea of architecture as a craft was stretched further by the exploration of used materials and found objects as constructional materials, for example the Telegraph Pole House in Langkawi by Building Bloc. The architects, BC and Wen Hsia, sourced recycled poles in the timber yards of Kedah, Kelantan and Trengganu (the north eastern part of Malaysia). The main structural frame and roof trusses were all 5x5 telegraph poles sourced from a timber yard in Kedah. The old poles are very beautiful found structures that have gone through the patina of time, and have maintained their soundness from impending termite attacks and weathering. The floorboards, wallboards, roof shingles were all salvaged from other buildings that were taken down. The tectonic of this dwelling echoes Mies van der Rohe's dictum of 'God is in the details'. Every column is a composite of 4 numbers of 5x5 poles connected to a steel pin base. The base also acts as a termite shield. The main beams of the house are made from 3 numbers of 5x5 poles.They are connected with scarf joints and multiple sections.

3 由回收石料建成的贝隆雨林度假村酒店入口/The entrance of Belum Resort made of recycled masonry

4 贝隆雨林度假村酒店的“乱”树苗墙/The 'huruhara' tree sapling walls of Belum

5 Boh茶园的圆木立面/The timber log facade of Boh Tea Centre

6 电线杆住宅的结构/The structure of Telegraph Pole House

Sensitivity of materials also reflects the character of the site. Set along the beachfront of Batu Ferringhi in Penang, the Lone Pine Resort by GDP Architects establishes the texture and tactility of various masonry types in its facade design to create a breathable skin. Whilst allowing ventilation, the variety of the single units and the order that it is assembled somehow forms a diversity of textured patterns which are clearly displayed without any finishes to disguise it. This approach reaffirms the spirit of the original hotel that was a jumble of sorts, a result of three sets of buildings in all, constructed over a period of sixty years.[10]

Contemporary interpretations of vernacular ideas

Malaysian architecture incorporates vernacular principles into their designs. Broadly defined,vernacular architecture refers to primitive shelter.In Malaysia, it commonly refers to the traditional Malay House. In Kevin Low's Louvrebox House,he raised the building on stilts to counter the challenging terrain without flattening the land.Inspired by the traditionalkampung house, he liberates the ground below for landscaping. This open lower ground allows for ventilation through the house. It is similar for Sekeping Serendah which is raised off the ground as protection from intruders and the elements. Another traditional Malay House essence is the 'Serambi' or the shaded open-sided verandah that is for greeting visitors or chatting with a neighbour. In Sek San's Jalan Tempinis Satu home, the entrance leads into a courtyard with a low timber deck.

7 龙柏酒店:通风砌块立面/Lone Pine Hotel: Vent block facade

8 龙柏酒店使用的各种通风砌块与砌砖工艺/The variety of ventilation blocks and brickwork used throughout the Lone Pine

In the same line, the Wooi House by Loke Wooi Architect reinterprets the traditional Malay House in attempt to recapture the soul of his childhood experiences of growing up in Pendang, Kedah. The Wooi House lends the idea of the kampong house's slanted roof by fitting a prominent umbrella roof made of zinc. The walls are constructed of timber strips that are placed vertically to allow air flow similar to that of a kampong house which is porous and breathable.[11]

Inside-out, Outside-in: Architecture beyond the four walls

The issue of enclosure and the relationship with nature were questions that contemporary Malaysian architecture explored.Should space be enclosed in four walls and a door? Unlike the 20th century modern architecture tore apart the concept of four walls and a door in defining architectural space due to influences of the concept of hygiene, the invention new construction material(reinforced concrete) and technology. The opening up of architecture to blur boundaries of inside and outside seeks to promote the symbiotic relationship between nature and architecture. Furthermore,Western ideas of the dialectic between architecture and nature were portrayed in the 18th and 19th centuries' emphases on gardens and the country houses. The idealisation of architecture from the perspective of the Arcadian landscapes was evident in art, architecture and literature.

In the local context, architecture explores the idea of turning architecture inside-out and outside-in. The use of trees outside and inside of architecture also allows architecture to grow.

In the PJ Trade Centre (designed by Kevin Mark Low of Small Projects, with Yellil Architect as the Architect of record), there is a natural element onalmost all four walls, floor and ceiling despite being a commercial office development.

9 一幢传统村屋的室外元素/The external elements of a traditional kampong house

10 百叶窗盒住宅正立面/Front elevation of the Louvrebox House

11 村屋的会客空间/The serambi of a kampong house

12 淡宾尼一道的入口庭院/The entrance courtyard of Jalan Tempinis Satu

…good architecture begins with the garden.——Kevin Mark Low[12]

After the more solid concrete ventilation block facade, the Centre reveals a garden courtyard which is visible through the more transparent inner walls of the offices. It seems as if the trees were put in place first and the walls came up around them.The sky terraces punctuate the area bridging the ventilation block screen and the offices provide a garden space at higher levels. This is empowerment of nature is echoed by trees growing out from the basement car park floors through each level.[13]Low believes that architecture should be about unclosure of space and the unarchitecture of buildings. He stresses that the garden is not merely designed around good architecture and beauty can come from non-architectural components of a building.

The global-local dialectic has paved way for alternative philosophical concern and practice of architecture in Malaysia. Rebutting the questions on style, there emerges an alternative approach to contemporary Malaysian architecture that embraces the global, the traditional and the local and perceives such concepts as not mutually exclusive. Contemporary architectural thoughts and ideas do not emerge from a vacuum. Rather,they are formed by a convergence of philosophical,economical, historical and socio-cultural influences.Despite the different physical manifestations of architecture, the core philosophy stems from the concerns of place-specific architecture that returns to the fundamental basis of architecture economy,humanity and place.

The definition of identity in architecture is a polemic issue. What identity? Whose identity?The architectural discourse is constantly faced with the problem of identity because identity is transient. Identity is governed by place and time which are never static. In order to respond to the unique position of defining the 'here' and 'now',the awareness of the global context and the local context will continue to forge path in defining and re-defining the identity of contemporary Malaysian architecture. One of the contemporary approaches to architecture is indeed 'glocal'.□

注释/Notes:

[1] RICOUER, P. (1961) 'Universal Civilization and National Cultures'. In History and Truth, trans. Chas.A. Kelbley. Evanston: Northwestern University Press,1965: 276-277.

[2] In the book Place & Placelessness (1976), Edward Relph defined placelessness as environments that lack a sense of identity.

13 洛克住宅的斜屋顶/The slanted roof of Loke Residence

14 木条墙面/The timber strip walls

15 八打灵再也贸易中心的挑空平台/The sky terraces of PJ Trade Centre

16 从地下车库生长出来的树木/The trees growing through the basement car park levels

17 玻璃墙面使门厅向庭院花园敞开空间/The glass walls opening up the lobby to the courtyard garden

[3] GIDDENS, A. 1990, The consequences of modernity, Oxford: Polity Press.尽管很难追踪到“全球本土化”术语在原日语中的首位使用者,英语中的首位使用者是罗兰·罗伯森教授。他是一位英美社会学家,从英国移居美国,并在美国宾夕法尼亚州的匹兹堡大学度过了大部分学术生涯。罗伯森原来在社会学中的研究方向是宗教社会学、社会学理论和文化社会学,其研究也涉猎比较社会学和现代化研究领域。/Although it would be difficult to trace the first user of the term 'glocalisation' in its original Japanese usage, the first time the term was used in English can be attributed to Professor Roland Robertson, a British/American sociologist,who migrated from United Kingdom to the United States where he spent most of his academic career at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.Robertson's original interests in sociology were in the areas of sociology of religion, sociological theories and cultural sociology. He also ventured into areas of comparative sociology and modernization studies.

[4] FRAMPTON, K. 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture:The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. New York: The MIT Press: 27.

[5] NORBERG-SCHULZ, C. 1996. 'The Phenomenon of Place (1976)'. In Theorizing A New Agenda For Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995. Nesbitt, K. (ed). Princeton Architectural Press: 426.

[6] HARRIES, K. 1996. 'The Ethical Function of Architecture (1975)'. In Theorizing A New Agenda For Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995. Nesbitt, K. (ed). Princeton Architectural Press: 396.

[7] OOI, Lina. C'Arch Architects: Belum Rainforest Resort.

[8] BALSUTO, David. 2008. Boh Tea Centre/ZLG Design.

[9] FRAMPTON, K. 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture:The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. New York: The MIT Press.

[10] GDP Architects on Lone Pine Resort. http://www.gdparchitects.com/projects/category/hotel/lone-pine-hotel.html

[11] YOONG, Yvonne. 2005. 'Wooi's Wow Factor'. In New Straits Times, February 19.

[12] LOW, Kevin Mark. Small projects, http://www.small-projects.com/#

[13] TONG, Ching Thing. 'The Bare Mark' Space Out Magazine.