A selective approach to the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients and its outcome

Omar J Shah, Irfan Robbani, Parveen Shah, Sadaf A Bangri, Irfan J Khan, Mohammad Y Bhat and Manmohan Singh

Kashmir, India

A selective approach to the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients and its outcome

Omar J Shah, Irfan Robbani, Parveen Shah, Sadaf A Bangri, Irfan J Khan, Mohammad Y Bhat and Manmohan Singh

Kashmir, India

BACKGROUND:Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a high risk, complex, technically challenging operation associated with significant perioperative morbidity and mortality. This study on the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients is based on our experience in a period of nearly 13 years.

METHODS:The study was conducted on two groups of patients: group A included 42 patients who were treated between January 2000 and September 2005 and group B included 134 patients who were treated between October 2005 to October 2012. Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative details of all these patients were collected, tabulated and analyzed to assess the impact of the selective approach introduced in the department with effect from October 2005.

RESULTS:Intraoperative details revealed highly significant differences in the management of the two groups of patients in respect of operative time (250.4 vs 126.6 minutes;P<0.001), operative blood loss (1070.2 vs 414.9 mL;P<0.001) and intraoperative blood transfusion (1.4 vs 0.2 units;P<0.001). Variations between the two groups in the frequency of complications were found to be statistically insignificant. However, the difference between the two groups in the overall morbidity of patients (47.6% vs 26.1%;P=0.009) and the length of their hospital stay (11.8 vs 7.8 days;P<0.001) were significant.CONCLUSION:A selective approach applied to the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients is a step in the right direction.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:628-633)

pancreaticoduodenectomy;

superior approach technique;

Whipple's operation

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is the only effective surgical option available for the management of pancreatic and periampullary malignancy although it is considered a high risk surgical procedure with considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality. Given the limited number of long-term survivors among PD patients, it is imperative that its postoperative morbidity and mortality was reduced to the extent possible. In this connection, the empirical relationship established by Luft and colleagues[1]and another study[2]between higher surgical volume and lower postoperative mortality holds promise.

With this end in view, it was in October 2005 that the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology was created within the surgical division of Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS) in the Indian valley of Kashmir. And a team of skilled and experienced hepatopancreato-biliary surgeons was constituted out of the in-service manpower of the surgical division of SKIMS and entrusted with responsibility of establishing and organizing the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology on modern lines for extending tertiary care services to deserving patients and in the process growing into a high volume center registering a declining postoperative morbidity and mortality trend.

Methods

The patients of periampullary cancer who had undergone PD in SKIMS before and after the creation of the Department of Surgical Gastroenterologyconstituted the material for this study. To study the impact of selective approach introduced by the department after October 2005, all the patients that were treated between January 2000 and September 2005 were included in group A and the rest who were treated between October 2005 and October 2012 in group B. To facilitate objective assessment of the treatment modalities applied to the two groups of patients, all the necessary information was retrieved from the records section of the department. The information consisted of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative details of patients. This information was analyzed and tabulated to facilitate a comparative assessment of the kind of treatment received by the two groups as also the outcome of the selective treatment extended to group B patients. Group A consisted of 42 patients and group B 134; 26 patients in group A were treated by classical Whipple's procedure and the remaining 16 patients were subjected to classical pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenostomy (PPPD) procedure. In group A, pancreaticojejunostomy was performed by duct to mucosa (38 patients) or invagination (4 patients) method; end to side gastrojejunostomy was performed in a retrocolic or antecolic fashion. All the patients in group B were treated by a single team with a modified PPPD approach, developed by our group and here referred to as the superior approach technique.[3]This technique involves early ligation and division of gastroduodenal and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries.

In group B, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was carried out by invagination method in all patients. No pancreatic stent was used; after end to side hepaticojejunostomy, an antecolic duodenojejunostomy was carried out. Bedsides duodenojejunal anastomosis, pyloric dilatation was performed by metal sizers of 28-34 mm in diameter.

Five patients who had two staged PD were excluded from the study; no patient received prophylactic octreotide or neoadjuvant therapy. None of the patients underwent extended lymphadenectomy or portal vein resection. Postoperative complications were classified as per Clavien and Dindo criteria.[4,5]Accordingly a postoperative pancreatic fistula was defined as a drain output of a measurable volume of fluid appearing on or after the third postoperative day, with amylase content three times greater than the serum amylase level. Pancreatic fistulas were graded as A, B and C as per the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF).[6]Delayed gastric emptying was pronounced where there was a need for a nasogastric tube for 3 days or a need for its reinsertion after the third postoperative day or the patient was unable to tolerate solid food after the seventh postoperative day.[7]

Mortality and morbidity rates were computed on the basis of deaths and complications occurring within 30 days of surgery. Post discharge follow-up schedule of patients comprised three monthly clinic reviews in the first two years, half yearly reviews in the subsequent three years and yearly follow-up visits thereafter. All statistical tests were performed with statistical software (SPSS version 16) including the independent t test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was made with and without Yate's continuity correction. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The age and gender distribution of patients in both groups was similar. There were 25 male and 17 female patients in group A and 79 male and 55 female patients in group B. The age of patients ranged between 42 and 83 years in group A and between 40 and 83 years in group B. The mean age of patients was 62.3 years in group A and 60.7 years in group B. All these differences were statistically insignificant. The preoperative profile of patients is presented in Table 1. This table gives information on the distribution of various types of periampullary adenocarcinoma between the two groups, their American Society for Anesthesiologists (ASA)risk scores, and their co-existing medical conditions. Obviously, the two groups of patients are similar in all respects and well-matched; minor variations, if any, are statistically insignificant. It may be added here that the mean preoperative levels of hemoglobin and albumin were 9.7 mg/dL and 3.3 mg/dL in group A and 9.6 mg/dL and 3.4 mg/dL in group B, respectively. Biliary stenting was performed in 6 patients in group A and 15 patients in group B.

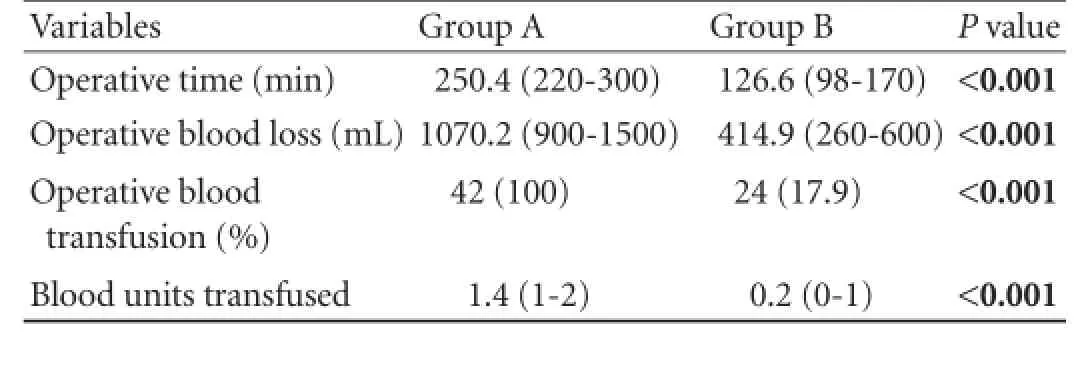

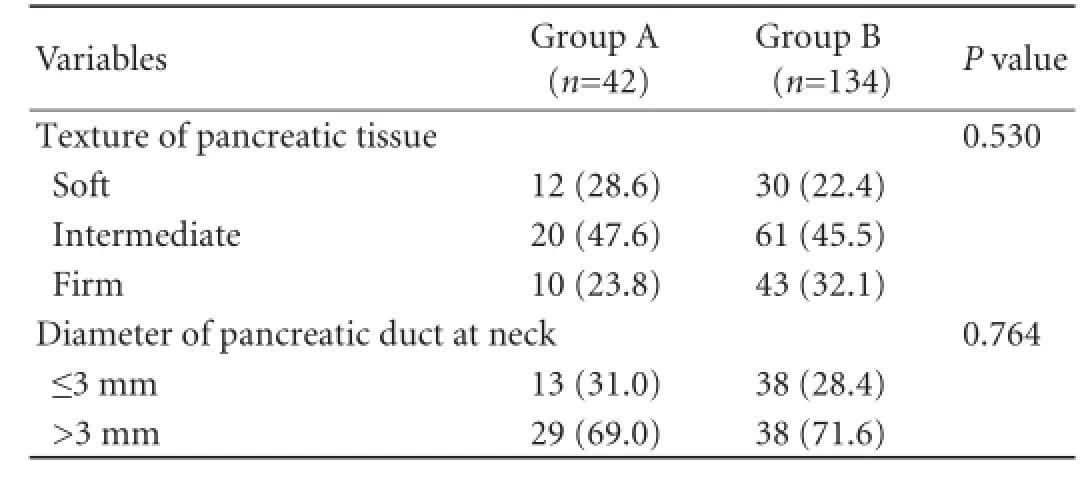

Intraoperative details of patients relating to operative time, operative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion and the diameter of the pancreatic duct are presented in Table 2. All these differences between the two groups were statistically highly significant (P<0.001). The intergroup differences in the texture of the affected pancreatic tissue and the diameter of pancreatic ducts at their neck levels were statistically insignificant (Table 3).

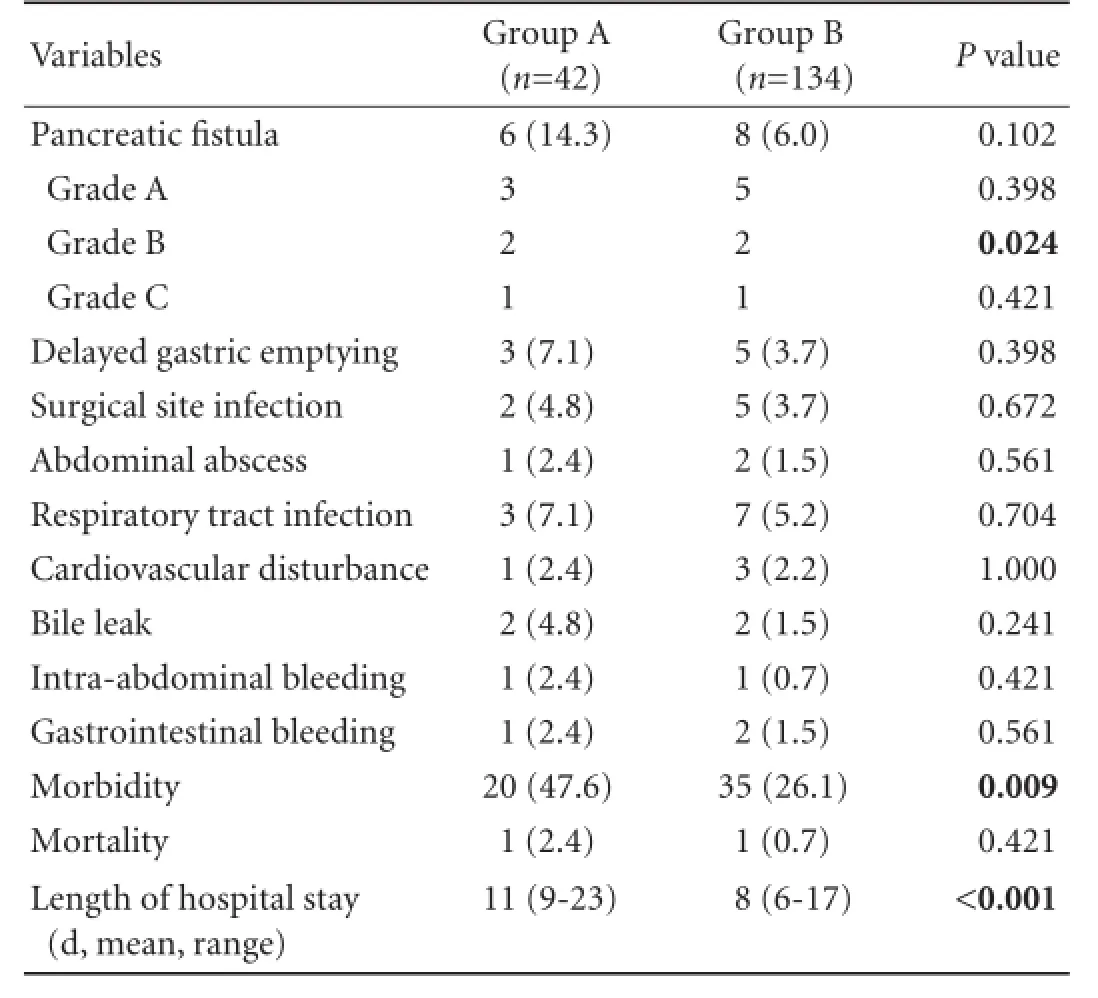

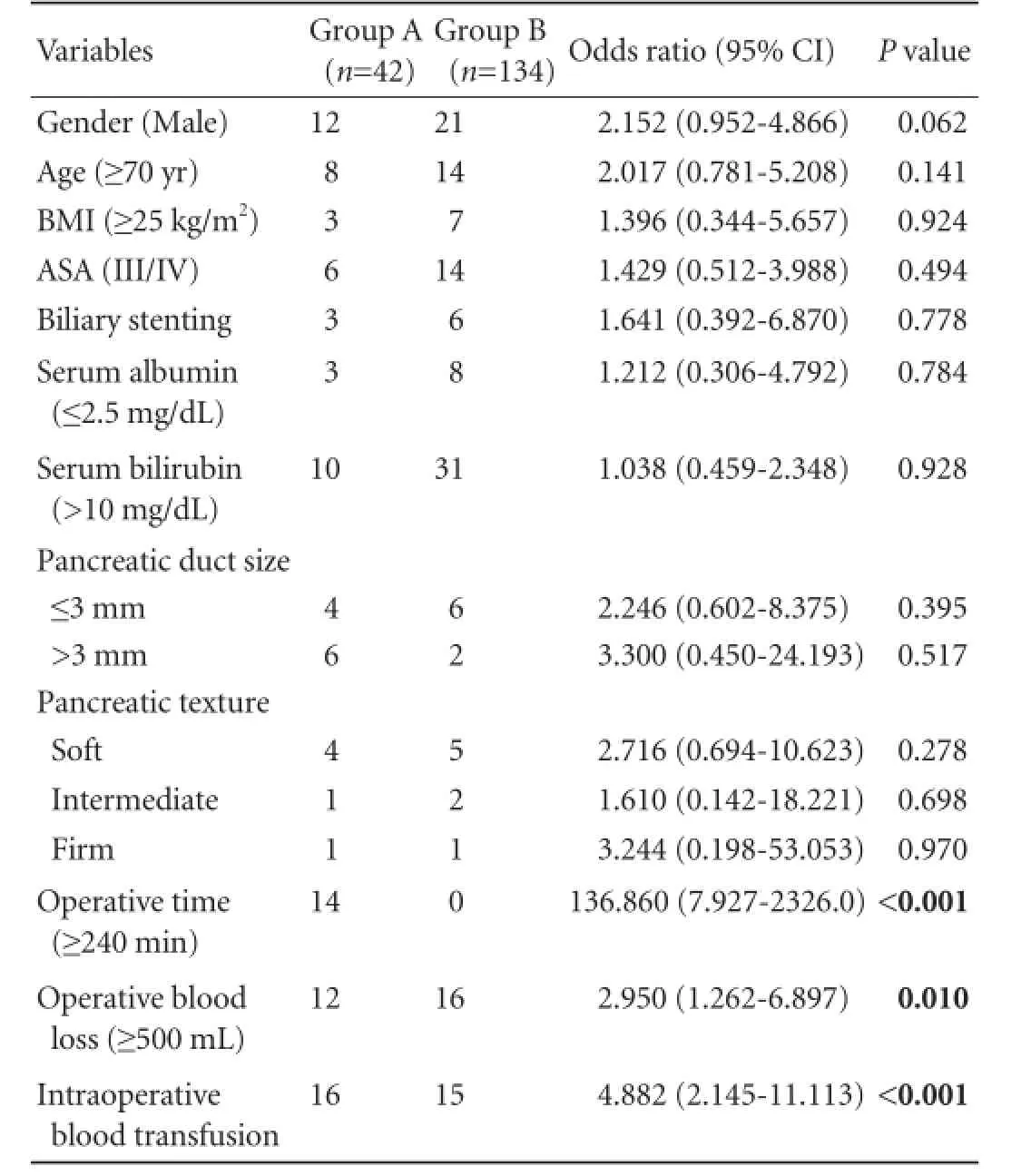

The postoperative complications in the two groups of patients including delayed gastric emptying, infection at the surgical site and the appearance of pancreatic fistulas, bile leak, intra-abdominal bleeding, abdominal abscess, respiratory tract infection and cardiovascular disturbance are given in Table 4. The majority of types of complications in both groups were similar and the variations between the two groups were found to be statistically insignificant. However the overall morbidity in group B was found statistically significant when compared with group A (26.1% vs 47.6%;P=0.009). The length of hospital stay ranged between 9-23 days in group A and between 6-17 days in group B patients. The differences in the rate of overall morbidity and the length of hospital stay were statistically significant. Univariate analysis of factors associated with complications revealed that operative time, operative blood loss and requirement of blood transfusion were statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 2.Intraoperative profile

Table 3.Particulars of affected pancreas (n, %)

Table 4.Postoperative profile (n, %)

Table 5.Univariate analysis of factors associated with complications between the two groups

Discussion

Despite a history of more than 100 years, PD remains a formidable and lengthy procedure with substantial risks. Although the mortality rate related to this operation has dramatically reduced from more than 20% in the 1970s to less than 3% at present, the morbidity has remained relatively consistent at approximately 40%.[8-10]PD continues to remain associated with challenging postoperative complications. Among these, delayed gastric emptying known to occur in 15%-45% of patients after PPPD is a frustrating problem usually faced by surgeons.[11,12]The factors responsible for this complication are multiple and include postoperative sepsis, appearance of biliary or pancreatic fistulas, decreased plasma motilin concentration and the nature of surgical procedure applied to patients.[13]The denervation and devascularization of the pylorus during PD can lead to pylorospasm which can delay gastric emptying. However, if pyloric dilatation is performed during surgery, it can temporarily weaken the grip of pyloric muscle and allow smooth passage of food during the postoperative period.[14]Manes et al[15]reported a decrease in the incidence of delayed gastric emptying with pyloric dilatation. Antecolic duodenojejunostomy facilitates increased mobility of the stomach and provides an anatomical barrier against the pancreas.

Encouraging results have been achieved in this direction as reflected in several reports. In our study, the frequency of postoperative complications was not materially different between the two groups of patients except for postoperative morbidity rate and the length of hospital stay of patients; both of which were significantly less among group B patients. The steady improvement shown by our team in the management of patients with periampullary cancer is due to several factors, the most important being our switch over from the classical PPPD operation to a modified PPPD technique referred to as a superior approach technique. This technique was developed and standardized by our department after October 2005. Other factors contributing to improved performance are dedication and commitment of our surgical and supportive staff as also our adherence to a standardized patient management protocol. This is in tandem with the global phenomenon of growing subspecialty based surgical practice, regionalization of apical surgical care and establishment of high volume centers in response to increasing patient volumes. Birkmeyer and colleagues[16]demonstrated the relationship between hospital volume and surgical mortality for complex surgical procedures including PD which has been confirmed several times with reported mortality rates of less than 4% in high volume centers versus over 12% in low volume centers.[16-18]High volume centers offer high quality patient care through specially trained and technically competent surgeons using advanced technology in the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative settings with commendable results. In high volume centers, increasing surgeon frequency is directly related to increasing hospital volume. More recent analyses of the volume-outcome relationship have shown that surgeon characteristics and system resources, not merely hospital volume, are the underlying factors that determine the outcome and are more likely to be present at a high volume center.[19,20]It seems that both hospital volume and surgeon volume interact synergistically towards an improved outcome.

Greater surgeon frequency or experience has been shown to be associated with shorter length of stay, lower patient morbidity and mortality and of course decreased hospital charges.[21,22]These factors are independent of hospital volume; experience of surgeons determines the quality of patient outcome. According to Schmidt et al,[23]surgeons with less experience (less than 50 PDs) perform with more complications, more operative blood loss and more operative time than those with more experience (more than 50 PDs). Kennedy et al[24]reported that surgeons with 10 or more PDs experience per year performed much better in terms of morbidity than surgeons with less experience.

A US study covering 39 hospitals has classified hospitals into 3 categories on the basis of their frequency of PD operations and their associated mortality. According to this classification a hospital conducting more than 20 PD cases per year with a mortality of 2.2% is a high volume center; a hospital conducting 6-20 PD cases per year with a mortality of 12% is a medium volume center; and a hospital conducting 1-5 cases of PD per year with a mortality of 19% is a low volume center.[25]As per to this classification, by performing 15 PD operations per year, our department falls in the category of medium volume centers; and by having a mortality rate of 1.1%, it excels even the performance of a high volume center.[26,27]

By introducing a modified technique of PD, our team has succeeded in reducing intraoperative blood loss in diminishing intraoperative blood transfusion requirement and in shortening the operative time undertaken. All these differences between the two groups were highly significant. Nevertheless, the experience and competence of operating surgeons and the role of non-technical skills in the management of patients cannot be underestimated. Lack of team work,[28]lack of decision making[29]and behavior failure[30]rather thandeficiency in technical experience are being reported as contributing positively to poor surgical outcome. These intangible non-technical factors are regarded as important, and sometimes even more important, in ensuring optimum surgical outcome. We feel that dedication and commitment of surgical team are equally desirable attributes that can contribute to better performance.

It is clear, therefore, that subspecialization of surgical services and regionalization of care reserving complex surgical procedures for distinct centers improve the outcome of PD and reduce the associated morbidity and mortality of patients. These centers should excel in the quality of team work, intensive care management and interventional radiology support. This will ensure selective surgical approach to the patients suffering from periampullary cancer.

Acknowledgement:We thank Rayees A Dar, Statistician SKIMS, who performed statistical analysis for this paper.

Contributors:SOJ proposed the study. SOJ, RI and KIJ performed research and wrote the first draft. SP, BSA, BMY and SM collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SOJ is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:The study is approved by the Institutional Ethical Board.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1364-1369.

2 de Wilde RF, Besselink MG, van der Tweel I, de Hingh IH, van Eijck CH, Dejong CH, et al. Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality. Br J Surg 2012;99:404-410.

3 Shah OJ, Gagloo MA, Khan IJ, Ahmad R, Bano S. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comparison of superior approach with classical Whipple's technique. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:196-203.

4 Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery 1992;111:518-526.

5 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

6 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

7 Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761-768.

8 Crile G Jr. The advantages of bypass operations over radical pancreatoduodenectomy in the treatment of pancreatic carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1970;130:1049-1053.

9 Herter FP, Cooperman AM, Ahlborn TN, Antinori C. Surgical experience with pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Ann Surg 1982;195:274-281.

10 Poon RT, Fan ST. Decreasing the pancreatic leak rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Adv Surg 2008;42:33-48.

11 Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreatico duodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg 1997;226:248-260.

12 Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Kaufman HS, Coleman J. One hundred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without mortality. Ann Surg 1993;217:430-438.

13 Tani M, Terasawa H, Kawai M, Ina S, Hirono S, Uchiyama K, et al. Improvement of delayed gastric emptying in pyloruspreserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 2006;243:316-320.

14 Kim DK, Hindenburg AA, Sharma SK, Suk CH, Gress FG, Staszewski H, et al. Is pylorospasm a cause of delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy? Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:222-227.

15 Manes K, Lytras D, Avgerinos C, Delis S, Dervenis C. Antecolic gastrointestinal reconstruction with pylorus dilatation. Does it improve delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy? HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:472-476.

16 Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128-1137.

17 Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on inhospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 1999;125:250-256.

18 Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2128-2137.

19 Joseph B, Morton JM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Rubinfeld I, Faraj C, Velanovich V. Relationship between hospital volume, system clinical resources, and mortality in pancreatic resection. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:520-527.

20 Teh SH, Diggs BS, Deveney CW, Sheppard BC. Patient and hospital characteristics on the variance of perioperative outcomes for pancreatic resection in the United States: a plea for outcome-based and not volume-based referral guidelines. Arch Surg 2009;144:713-721.

21 Rosemurgy A, Cowgill S, Coe B, Thomas A, Al-Saadi S, Goldin S, et al. Frequency with which surgeons undertake pancreaticoduodenectomy continues to determine length of stay, hospital charges, and in-hospital mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:442-449.

22 Rosemurgy AS, Bloomston M, Serafini FM, Coon B, Murr MM, Carey LC. Frequency with which surgeons undertake pancreaticoduodenectomy determines length of stay, hospital charges, and in-hospital mortality. J Gastrointest Surg2001;5:21-26.

23 Schmidt CM, Turrini O, Parikh P, House MG, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, et al. Effect of hospital volume, surgeon experience, and surgeon volume on patient outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg 2010;145:634-640.

24 Kennedy TJ, Cassera MA, Wolf R, Swanstrom LL, Hansen PD. Surgeon volume versus morbidity and cost in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy in an academic community medical center. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1990-1996.

25 Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg 1995;221:43-49.

26 Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. Hospital volume influences outcome in patients undergoing pancreatic resection for cancer. West J Med 1996;165:294-300.

27 Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg 2000;232:786-795.

28 Christian CK, Gustafson ML, Roth EM, Sheridan TB, Gandhi TK, Dwyer K, et al. A prospective study of patient safety in the operating room. Surgery 2006;139:159-173.

29 Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Rogers SO, Zinner MJ, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:533-540.

30 Bogner M, ed. Misadventures in health care. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004.

Received July 10, 2013

Accepted after revision March 31, 2014

Author Affiliations: Departments of Surgical Gastroenterology (Shah OJ, Bangri SA, Khan IJ, Bhat MY and Singh M), Radiodiagnosis & Imaging (Robbani I) and Pathology (Shah P), Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Kashmir, India

Omar J Shah, MD, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Kashmir, India (Tel: +91-0194-2463774; Fax: +91-0194-2471898; Email: omarjshah@yahoo.com)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60262-9

Published online May 29, 2014.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- A new approach for Roux-en-Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Surgical treatment of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: an underestimated malignant tumor?

- Comparison of brush and basket cytology in differential diagnosis of bile duct stricture at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- Effect of the number of positive lymph nodes and lymph node ratio on prognosis of patients after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience with 100 patients

- Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia arising from an ectopic pancreas in the small bowel