Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience with 100 patients

Lei Xin, Yuan-Xiang He, Xiao-Fei Zhu, Qun-Hua Zhang, Liang-Hao Hu, Duo-Wu Zou, Zhen-Dong Jin, Xue-Jiao Chang, Jian-Ming Zheng, Chang-Jing Zuo, Cheng-Wei Shao, Gang Jin, Zhuan Liao and Zhao-Shen Li

Shanghai, China

Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience with 100 patients

Lei Xin, Yuan-Xiang He, Xiao-Fei Zhu, Qun-Hua Zhang, Liang-Hao Hu, Duo-Wu Zou, Zhen-Dong Jin, Xue-Jiao Chang, Jian-Ming Zheng, Chang-Jing Zuo, Cheng-Wei Shao, Gang Jin, Zhuan Liao and Zhao-Shen Li

Shanghai, China

BACKGROUND:Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is increasingly recognized as a unique subtype of pancreatitis. This study aimed to analyze the diagnosis and treatment of AIP patients from a tertiary care center in China.

METHODS:One hundred patients with AIP who had been treated from January 2005 to December 2012 in our hospital were enrolled in this study. We retrospectively reviewed the data of clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging examinations, pathological examinations, treatment and outcomes of the patients.

RESULTS:The median age of the patients at onset was 57 years (range 23-82) with a male to female ratio of 8.1:1. The common manifestations of the patients included obstructive jaundice (49 patients, 49.0%), abdominal pain (30, 30.0%), and acute pancreatitis (11, 11.0%). Biliary involvement was one of the most extrapancreatic manifestations (64, 64.0%). Fifty-six (56.0%) and 43 (43.0%) patients were classified into focaltype and diffuse-type respectively according to the imaging examinations. The levels of serum IgG and IgG4 were elevated in 69.4% (43/62) and 92.0% (69/75) patients. Pathological analysis of specimens from 27 patients supported the diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, and marked (>10 cells/HPF) IgG4 positive cells were found in 20 (74.1%) patients.Steroid treatment and surgery as the main initial treatments were given to 41 (41.0%) and 28 (28.0%) patients, respectively. The remission rate after the initial treatment was 85.0%. Steroid was given as the treatment after relapse in most of the patients and the total remission rate at the end of follow-up was 96.0%.CONCLUSIONS:Clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging and pathology examinations in combination could increase the diagnostic accuracy of AIP. Steroid treatment with an initial dose of 30 or 40 mg prednisone is effective and safe in most patients with AIP.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:642-648)

autoimmune pancreatitis;

immunoglobulin G4;

steroid treatment

Introduction

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is an unique form of pancreatitis characterized by elevated levels of serum immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4), prominent infiltration of IgG4 positive plasma cells in multiorgans, and good response to steroid treatment.[1]Since the pancreatitis associated with obstructive jaundice and hypergammaglobulinemia was first reported by Sarles et al,[2]there has been gradual progress in understanding this rare pancreatic disease. This disease was termed as autoimmune pancreatitis in 1995 by Yoshida et al.[3]Now, AIP is mainly recognized to be part of a systemic fibroinflammatory syndrome complex known as IgG4-related disease. Moreover, type 2 AIP, characterized by intraductal neutrophilic infiltration and no IgG4 elevation, has been reported worldwide.[4]Although there has been increasing awareness of AIP over the last decade and an International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for AIP has been reached,[1]the differential diagnosis between AIP and pancreaticcancer, management of relapse after initial steroid treatment and long-term prognosis of AIP still require further study.

The incidence of chronic pancreatitis (CP) is rising rapidly in recent years in China,[5]and the number of AIP patients is theoretically considerable according to the reported AIP/CP ratio.[6]But there are only a few reports on Chinese population.[7-10]The present study aimed to systematically analyze the clinical features, diagnosis, management and outcomes of a large number of patients with AIP at a tertiary care center in China.

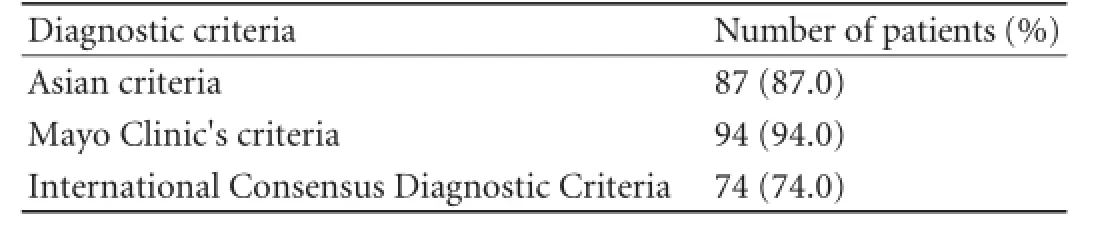

Table 1.The proportion of these 100 AIP patients meeting the three criteria

Methods

Patients

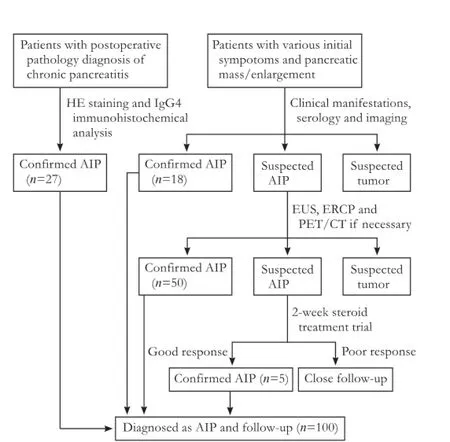

Using the search terms "autoimmune pancreatitis", "lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis" and "chronic pancreatitis with autoimmune diseases", we identified patients with suspected AIP in the medical records of Shanghai Changhai Hospital between January 2005 and December 2012. The records of patients with pathological diagnosis of CP after surgery from January 2005 to December 2012 were also reviewed. In these patients, pancreatic specimens must be sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and IgG4 immunohistochemical analysis was made. AIP was diagnosed according to the Asian diagnostic criteria,[11]Mayo Clinic's HISORt criteria[12]or ICDC,[1]and it was confirmed by the follow-up data. Finally, 100 patients were enrolled in the study (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Changhai Hospital.

Data collection

Clinical manifestations, imaging studies, laboratory tests, pathological diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of the patients were retrieved from the database or via follow-up. Clinical manifestations included main symptoms and extrapancreatic manifestations. Extrapancreatic lesions included biliary involvement, retroperitoneal fibrosis, lachrymal gland swelling, sialadenitis, inflammatory bowel disease, etc. Because the imaging data of some patients were not available for detailed analysis, the imaging manifestations of biliary involvement were only classified into the biliary stricture located in the lower part of the common bile duct or in the hilar/intrahepatic bile duct. Laboratory tests included biochemical tests, autoimmune antibodies, IgG, IgG4, CA19-9, etc. The upper limits of normal serum IgG and IgG4 were 15.0 g/L and 2.0 g/L, respectively. The systematically reviewed pre- and posttreatment imaging examinations included computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging/cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and18F-FDG PET/CT. AIP patients were classified into focal-type and diffuse-type according to the imaging examinations. Focal or mass-forming lesion was defined as focal-type and the swollen pancreas extending from the pancreatic head to tail was defined as diffuse-type.[13]

The treatment of the patients included use of steroid, surgery, ERCP biliary drainage, percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD), and nonspecified medication. Initially, oral prednisone of 30 or 40 mg was given for 4 weeks according to patient's body weight, and the dose was tapered by 5 mg every one or two weeks. Maintenance steroid treatment or discontinuation after the initial treatment depended on the outcomes. Surgeries were considered when typical AIP features were absent and malignancy could not be ruled out. Non-specified medication included oral pancreatic enzyme supplements, ursodeoxycholic acid,and other adjuvant medications. Response or remission was defined as the disappearance of symptoms and imaging manifestations in a short-term or long-term follow-up after the initial treatment, respectively.[14,15]Relapse was defined as reappearance of symptoms with the development of pancreatic and/or extrapancreatic abnormalities in imaging examinations and/or laboratory tests after initial resolution.[14,15]

Fig. 1.The flow chart of diagnosis of 100 AIP patients.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using Student'sttest. Proportions were compared using Fisher's exact test and the Chi-square test. Nonparametric quantitative variables were compared using the Mann-WhitneyUtest. APvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical manifestations

In the 100 patients with AIP, 89 men and 11 women with a male to female ratio of 8.1:1. The median age of the patients at onset was 57 years (range 23-82). The most common manifestation was obstructive jaundice (49 patients, 49.0%); 5 patients showed spontaneous remission and relapse of jaundice. The other manifestations included abdominal pain (30 patients, 30.0%), acute pancreatitis (11, 11.0%), steatorrhea (4, 4.0%), and new onset diabetes mellitus (1, 1.0%). Pancreatic mass or enlargement shown incidentally by imaging examinations in 5 asymptomatic patients was eventually diagnosed as AIP (Table 2).

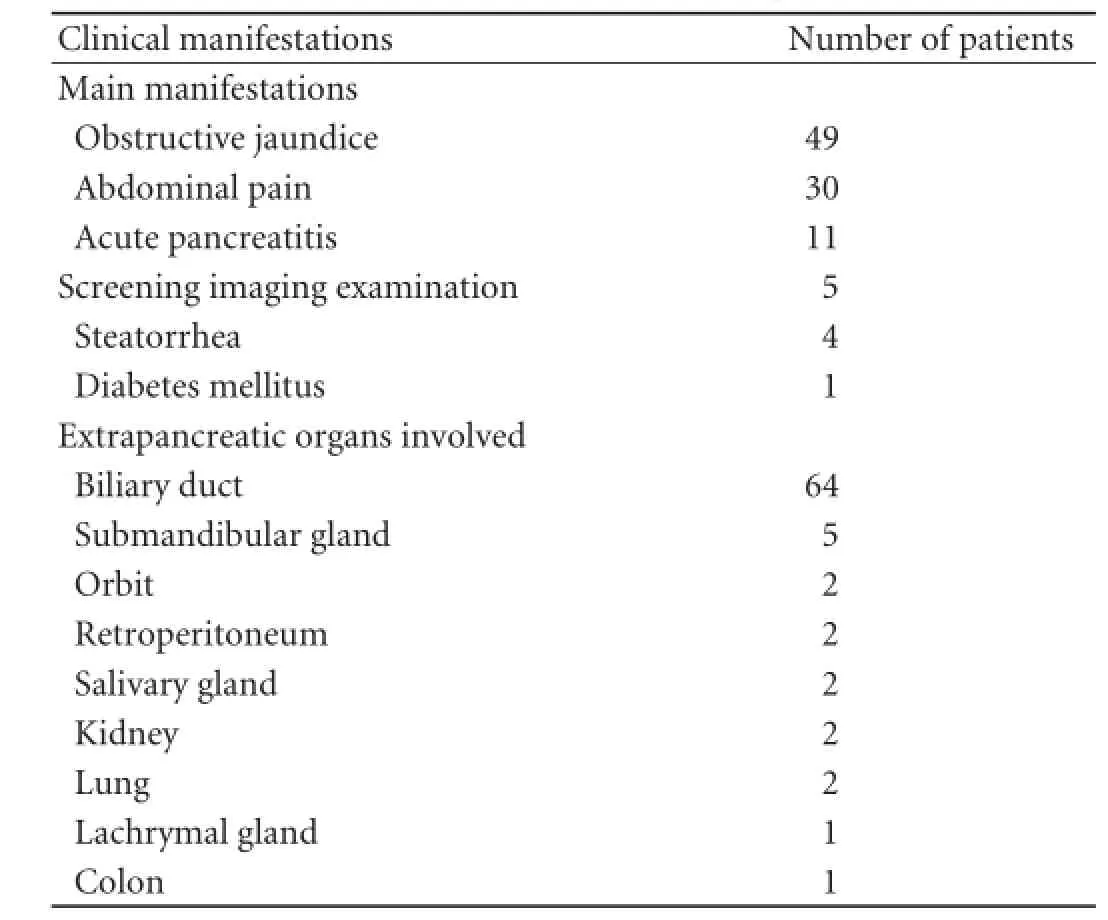

Table 2.The clinical manifestations of 100 patients with AIP

Eighty-one extrapancreatic lesions were observed in 77 (77.0%) patients. Biliary involvement was the most common extrapancreatic manifestation (64 patients, 64.0%). Forty-two (65.6%) patients had biliary stricture in the lower part of the common bile duct and 22 (34.4%) in hilar/intrahepatic bile ducts. Swelling submandibular glands were found in 5 patients and 2 of them were proved to have chronic sclerosing inflammation. Orbit swelling, retroperitoneal fibrosis, chronic sclerosing sialadenitis, interstitial nephritis and interstitial lung disease were found in 2 patients. Ulcerative colitis and swelling lachrymal gland were found in 1 patient (Table 2).

Imaging examinations

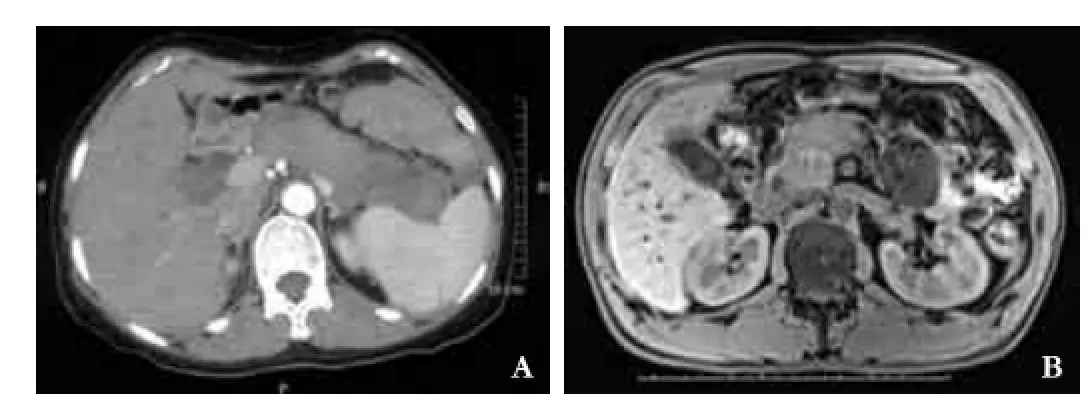

According to the pre-treatment CT or MRI examinations, 56 (56.0%) patients were classified into focal-type with the lesion mainly located in the head or the uncinate process (44 patients), the body (8), and the tail (4). Forty-three (43.0%) patients were classified into diffuse-type with sausage-shaped enlargement of the pancreas (Fig. 2). Moreover, the main imaging manifestation of one patient was multiple pancreatic pseudocysts.

Detailed data of enhanced CT were collected from 60 patients. Diffuse enlargement with delayed enhancement was found in 29 (48.3%) and rimlike enhancement in 16 (26.7%) patients. Focal enlargement with delayed enhancement was found in 31 (51.7%) patients and pancreatic calculi in 2 (3.3%) patients. Pancreatic pseudocysts were observed in 3 (5.0%) patients with a maximum diameter of 10.5 cm, and significant enlargement of peripancreatic lymph nodes were observed in 7 (11.7%) patients. Moreover, compression of the splenic vein was seen in 5 (8.3%) patients, two of whom had gastric varices. Retroperitoneal fibrosis was found in 2 (3.3%) patients with the involvement of the abdominal aorta and the left kidney in one patient, respectively.

Detailed data of the pancreatic duct were collected by MRCP/ERCP from 25 patients. A long stricture of the pancreatic duct (>1/3 length of the main pancreaticduct) or multiple strictures without marked upstream dilatation were seen in 7 (28.0%) and 3 (12.0%) patients, respectively. Marked upstream dilatation (duct size >5 mm) upon stricture was seen in 4 (16.0%) patients.

Fig. 2.A: The CT image of diffuse-type AIP with sausage-like pancreas;B: the MRI image of focal-type AIP with swelling in pancreatic head.

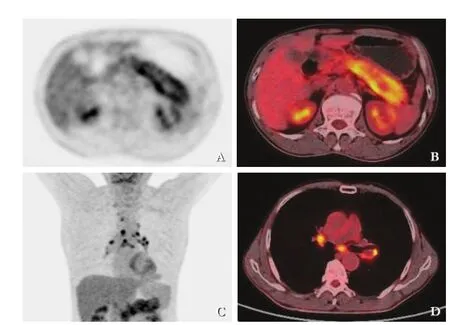

PET/CT was performed in 15 patients. The maximum standardized uptake value was increased in the whole pancreas in 13 (86.7%) patients and in focal lesions of the pancreas in 2 (13.3%) patients (Fig. 3). Extrapancreatic lesions with increased FDG uptake were found in 8 (53.3%) patients.

Laboratory tests

Serum IgG level increased to >15.0 g/L in 43 (69.4%) of 62 patients. Serum IgG4 level increased to >2.0 g/L in 69 (92.0%) of 75 patients, and among them, 56 (81.1%) patients showed that IgG4 was higher than 4.0 g/L. Both IgG and IgG4 were measured in the 56 patients, the positive rate of IgG4 was higher than that of IgG (92.9% vs 71.4%,P=0.008). Autoimmune antibodies were measured in 35 patients. Antinuclear antibody, anti-SSA antibody, and anti-SSB antibody were positive in 6 (17.1%), 4 (11.4%) and 3 (8.6%) patients respectively, and all the patients with positive autoimmune antibodies showed an elevated level of serum IgG4. Moreover, the levels of total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, serum IgE, and CA19-9 were increased in 54.1% (53/98), 33.7% (33/98), 28.2% (22/78), and 52.3% (45/86) patients, respectively.

Pathology

HE staining and IgG4 immunohistochemical analyses of specimens of 27 patients supported the diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis and none of them showed granulocyte epithelial lesions. Marked (>10 cells/HPF) IgG4 positive cells were found in 20 (74.1%) patients (Fig. 4). EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and biliary brush cytology during ERCP were performed in 45 (45.0%) and 5 (5.0%) patients, respectively. None of the cytology examinations showed malignant or atypical cells.

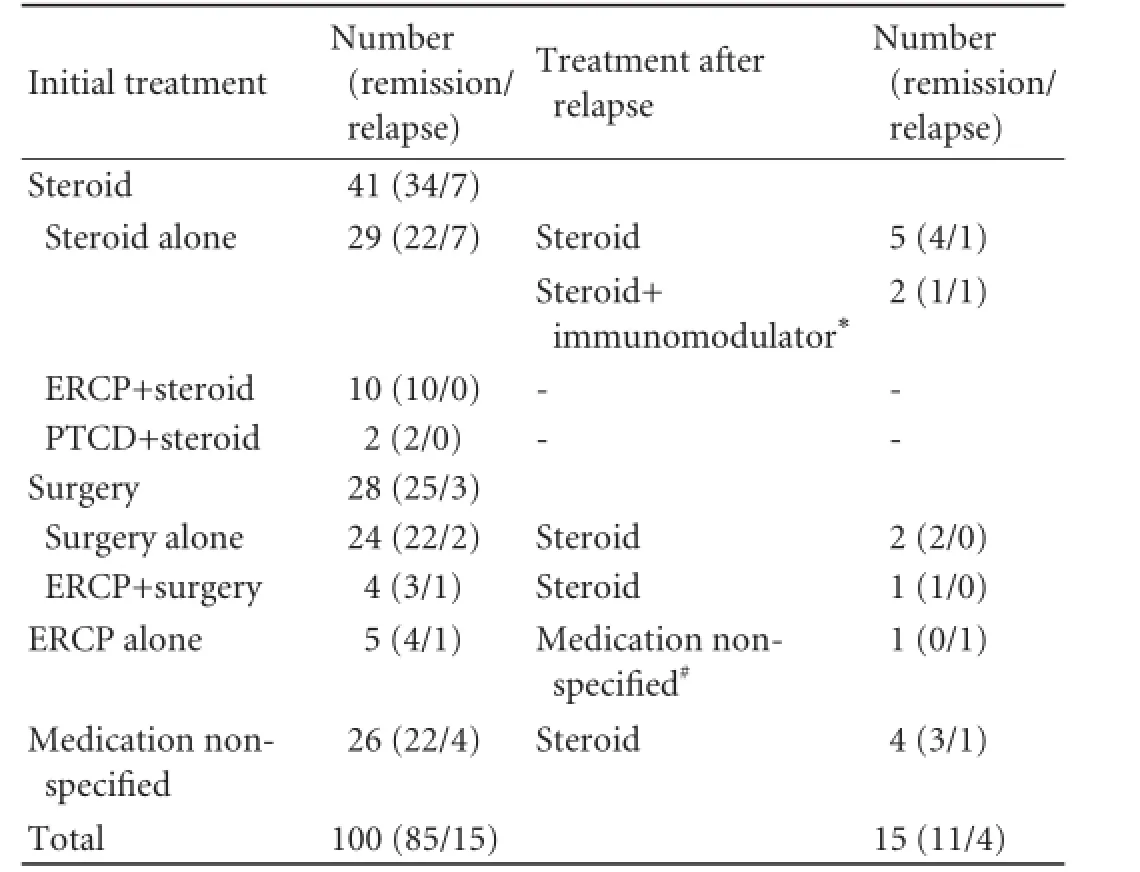

Treatment and follow-up

The mean follow-up duration was 494.0±271.5 days. The main treatment and outcomes of 100 patients with AIP at the end of follow-up are shown in Table 3. Steroid treatment was given to 41 (41.0%) patients as the main initial treatment, with 10 and 2 receiving ERCP biliary drainage or PTCD before steroid treatment, respectively. The initial dose of prednisone was 30 mg in 35 (85.4%) and 40 mg in 6 (14.6%) patients. The median duration of prednisone treatment was 14 weeks (range 10-42) and the response rate was 100.0% after the first course of treatment. The most common regimen was 30 mg asthe initial dose which was tapered 5 mg every 2 weeks and discontinued after 14 weeks (28 patients, 68.3%). Twenty-eight patients (28.0%) received surgeries as the main initial treatment for suspected malignancy, with 4 receiving preoperative ERCP biliary drainage. The surgical procedures included pancreatoduodenectomy (19 patients), distal pancreatectomy combined with splenectomy (7), radical resection of hilar cholangiocrcinoma (1), and choledochojejunostomy (1). The operative rate in patients of focal-type was higher than that of diffuse-type (44.6% vs 7.0%, OR=10.8 [3.0-38.9], P<0.001). Moreover, 5 (5.0%) patients received ERCP biliary drainage alone and 26 (26.0%) patients received non-specified medication.

Fig. 3.The PET/CT image of an AIP patient showed pancreas enlarged with increased diffuse FDG uptake and hilum of lungs and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 4.The pathological findings of AIP.A: HE staining showed the appearance of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis;B: The IgG4 staining showed a large amount of IgG4 positive cells.

Table 3.The main treatment of 100 patients with AIP until followup endpoint

After the initial treatment, remission and relapse occurred in 85 (85.0%) and 15 (15.0%) patients. The relapse rates of patients receiving steroid treatment, surgery, ERCP biliary drainage and non-specified medication as the main initial treatment were 17.1%, 10.7%, 20.0% and 15.4%, respectively. Steroid treatment was given as the treatment after relapse in 93.3% of the patients and the total remission rate until follow-up was 96.0%.

Minor complications related to steroid treatment included mild abdominal discomfort, insomnia, mild increase of blood glucose and others, and they were improved as steroid was tapered. Major complications occurred in one patient. He was given a standard steroid regimen with 30 mg prednisone as the initial dose and the symptoms reappeared 5 months after discontinuation of the treatment. He was re-treated with the same regimen of steroid. During the second course of treatment, he complained of abdominal pain, a sign of erosive gastritis shown by later gastroscopy. The patient was infected with herpes simplex virus. He was recovered after use of proton pump inhibitor and anti-virus medication.

Discussion

This study enrolled a largest series of AIP patients in China and systematically analyzed the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. The clinical features of these patients were consistent with the reports from other countries.[6,12,13]The combination of clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging and pathological examinations could increase the diagnostic rate of AIP. The fixed steroid regimen with an initial dose of 30 or 40 mg prednisone was effective in most patients with low rates of replase and complications.

The most common manifestation of AIP is obstructive jaundice, which mimics pancreatic cancer in its acute phase. In our study, obstructive jaundice was the main symptom in 49.0% of AIP patients, and 5 patients showed spontaneous remission and relapse of jaundice. The other manifestations included abdominal pain (30.0%) and symptoms related to acute pancreatitis (11.0%), steatorrhea (4.0%) and diabetes mellitus (1.0%). As diagnostic clues and evidence, extrapancreatic lesions are important and considered to be common in type 1 AIP. A Japanese survey[6]on 540 AIP patients revealed that the incidences of sclerosing cholangitis, sialadenitis, enlargement of mediastinal/abdominal lymph nodes and retroperitoneum were 53.4%, 14.1%, 12.8% and 8.1%, respectively. Another Korean survey[16]on 118 patients showed that the incidences of sclerosing cholangitis, sialadenitis, enlargement of mediastinal/ abdominal lymph nodes and retroperitoneum were 81%, 7%, 10% and 13%, respectively. However, the incidence of extrapancreatic lesions was lower than that of sclerosing cholangitis in our study. There are two possible explanations for this finding. First, the incidence of extrapancreatic lesions was lower in Chinese patients with AIP. In another report from China, the extrapancreatic lesions only included cholangitis (64.3%, 18/28) and retroperitoneal fibrosis (10.7%, 3/28),[8]which should be verified further. Secondly, we might ignore potential extrapancreatic lesions in the diagnostic process, especially in patients who underwent pathological examinations after surgery. Considering the importance of extrapancreatic lesions in the diagnosis of AIP, imaging or pathological examinations should be performed in patients with possible extrapancreatic involvement.

CT and MRI are main pancreatic parenchymal imaging techniques and play an essential role in the diagnosis of AIP. According to the ICDC, diffuse enlargement of the pancreas with delayed enhancement is a typical sign while segmental/focal enlargement with delayed enhancement is indeterminate/suggestive sign of imaging. However, the number of patients with focal-type AIP (56 patients) was more than that of diffuse-type (43 patients) in our study. This may demonstrate a real incidence of focal-type AIP in China or potential selection bias. As EUS-FNA and surgeries were used preferentially in patients with focal pancreatic lesion, the diagnosis of diffuse-type AIP might be underestimated in this study. In the ICDC, pancreatic calculi and pseudocysts are recognized as atypical manifestations, which were consistent with the results of our study. In the 60 patients with detailed data of enhanced CT, pancreatic calculi and pseudocysts were found in 2 (3.3%) and 3 (5.0%) patients, respectively. Dilation of the pancreatic duct was also recognized as a rare manifestation of AIP and used to differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancer. In our study, marked upstream dilatation (duct size >5 mm) upon stricture was seenin 16.0% (4/25) patients. In another study, imaging examinations of 45.5% (10/22) type 1 AIP patients revealed dilation of the pancreatic duct.[9]

Opinions on the ERCP diagnosis of AIP are different.[17-19]According to the study from Mayo Clinic, about 70% of suspected patients could be diagnosed with type 1 AIP non-invasively,[18]indicating that ERCP is not necessary for most of the patients. However, the Japanese consensus guidelines recognize ERCP as a mandatory diagnostic method.[19]The ICDC incorporated both opinions and the pancreatic ductal imaging in ERCP was considered as a diagnostic method. We consider that ERCP not only plays a role in the diagnosis of AIP but also shows the involvement of the biliary duct. In our study, the low proportion of patients receiving ERCP/MRCP contributed to the misdiagnosis of malignancy, especially in patients with focal AIP. The invasiveness of ERCP and the development of 3D MRCP enable MRCP to be an alternative of ERCP.

IgG4 is the only serum marker for type 1 AIP in the ICDC, and the sensitivity of IgG4 elevation varies between 44%-95% in different settings.[13,20-22]Moreover, marked elevation of IgG4 (>2 times upper limit of normal) is strongly suggestive of AIP in patients with obstructive jaundice/pancreatic mass.[1]In our study, IgG4 elevation to >2.0 and >4.0 g/L was observed in 92.0% and 74.7% patients. The relatively high proportion of elevated IgG4 patients indicated the importance of this marker in our clinical practice and the possible missing of patients with normal serum IgG4 level. Autoimmune antibodies were excluded from the ICDC because of their low diagnostic value. In our study, the positive rates of antinuclear antibody, anti-SSA antibody and anti-SSB antibody were relatively low. We consider that autoimmune antibodies only play a suggestive role when serum IgG4 is not available.

Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis is a pathological feature of type 1 AIP. However, the pathological evidence is difficult to obtain with mini-invasive technique. EUS-FNA is routinely used for the differentiation of AIP from pancreatic cancer. But its capability of providing adequate tissue samples for histopathological evaluation of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis is still controversial,[23,24]and most studies suggested that pancreatic core biopsies can be used when histopathological diagnosis of AIP is required.[25]In our study, EUS-FNA was performed in 45 (45.0%) patients and no specimen was adequate for histological evaluation.

Another subtype of AIP with neutrophilic infiltration in the epithelium of the pancreatic duct as a main pathologic manifestation has been increasingly reported in recent years. It is called type 2 AIP. According to the reports from different regions, type 1 AIP is the more common form worldwide and appears to be the exclusive subtype in Asia, but type 2 AIP seems to be common in Europe.[13,17]In our study we did not find any type 2 AIP and the reasons are as follows: first, the incidence of type 2 AIP is low in Asia.[6,26]in the previous reports from China, only a few patients were diagnosed as having type 2 AIP,[9]much less than those with type 1 AIP; second, type 2 AIP is difficult to diagnose because extrapancreatic involvement is rare, and specific serum markers are not available, and routine EUS-FNA or other biopsy techniques cannot obtain adequate tissues for histological diagnosis. Hence, patients with type 2 AIP are not easy to diagnose unless by surgery.

AIP is highly responsive to steroid treatment. However, 15% to 60% patients will relapse either during steroid tapering or after discontinuation.[27,28]In the present study, steroid was given to 41 patients as the main treatment, with an initial prednisone dose of 30 mg in 35 (85.4%) and 40 mg in 6 (14.6%) patients, respectively. The response rate was 100.0% and the relapse rate was 17.1%. In another study from two centers in China, the initial prednisone dose was 30 mg in 18 (64.3%) and 40 mg in 10 (35.7%) patients, and the the relapse rate was 28.6%.[8]These two preliminary studies suggested the relatively good response to steroid in Chinese patients with AIP. Major complications after steroid treatment were rarely reported previously.[20]In our study, one patient with erosive gastritis and infected with herpes simplex virus, which may be related to the infection during the steroid treatment.

In conclusion, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging and pathological examinations could increase the diagnostic rate of AIP and prevent patients from unnecessary operation. Steroid treatment with an initial dose of 30 or 40 mg prednisone is effective and safe in most Chinese patients with AIP.

Contributors:XL, HYX, and ZXF contributed equally to this work. ZQH and LZS proposed the study. LZ and LZS designed the study. XL, HYX and ZXF collected data and wrote the first draft. HLH,ZDW and JZD are responsible for the whole performance of the study. CXJ and ZJM reviewed the specimen from EUS-FNA or surgeries. ZCJ and SCW reviewed the imaging of AIP patients. JG provided the data about surgeries. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the study and to further drafts. LZS is the guarantor.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81270541) and Disciplinary Joint Research Projects of Changhai Hospital (CH125510312).

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Changhai Hospital.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011;40: 352-358.

要借助互联网的优点,把电视台节目的传播做到最大化,全面提高节目的传播度,使节目的受众群体不再是电视机前的用户,更要让互联网用户也能够及时获取电视节目中的信息,从而提高电视节目的影响力,扩宽受众群体。要加快节目的更新换代,发挥优势,打造节目品牌,立足眼前,放眼社会现象,结合当代形式,结合各个社交平台,例如微博、豆瓣、知乎等新媒体,在其中寻找大众接受并喜爱的节目题材,不能一味地选择抄袭优秀节目,获取流量,要做有想法、有创新、有责任感的新节目,为大众带来优良的电视节目的同时传播正确的价值观与人生观。?

2 Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, Guien C. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas--an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis 1961;6:688-698.

3 Yoshida K, Toki F, Takeuchi T, Watanabe S, Shiratori K, Hayashi N. Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:1561-1568.

4 Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, Sugumar A, Clain JE, Levy MJ, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:140-148.

5 Wang LW, Li ZS, Li SD, Jin ZD, Zou DW, Chen F. Prevalence and clinical features of chronic pancreatitis in China: a retrospective multicenter analysis over 10 years. Pancreas 2009;38:248-254.

6 Kanno A, Nishimori I, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Kuriyama S, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas 2012;41:835-839.

7 Song Y, Liu QD, Zhou NX, Zhang WZ, Wang DJ. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience from China. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:601-606.

8 Liu B, Li J, Yan LN, Sun HR, Liu T, Zhang ZX. Retrospective study of steroid therapy for patients with autoimmune pancreatitis in a Chinese population. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:569-574.

9 Zhang X, Zhang X, Li W, Jiang L, Zhang X, Guo Y, et al. Clinical analysis of 36 cases of autoimmune pancreatitis in China. PLoS One 2012;7:e44808.

10 Zhang MM, Zou DW, Wang Y, Zheng JM, Yang H, Jin ZD, et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasonography in the diagnosis of IgG4-negative autoimmune pancreatitis: A case report. J Interv Gastroenterol 2011;1:182-184.

11 Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, Kim MH, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, et al. Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus of the Japan-Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2008;43:403-408.

12 Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4: 1010-1016.

13 Frulloni L, Scattolini C, Falconi M, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Manfredi R, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: differences between the focal and diffuse forms in 87 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2288-2294.

14 Ghazale A, Chari ST. Optimising corticosteroid treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2007;56:1650-1652.

15 Kim HM, Chung MJ, Chung JB. Remission and relapse of autoimmune pancreatitis: focusing on corticosteroid treatment. Pancreas 2010;39:555-560.

16 Kamisawa T, Kim MH, Liao WC, Liu Q, Balakrishnan V, Okazaki K, et al. Clinical characteristics of 327 Asian patients with autoimmune pancreatitis based on Asian diagnostic criteria. Pancreas 2011;40:200-205.

17 Lerch MM, Mayerle J. The benefits of diagnostic ERCP in autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2011;60:565-566.

18 Sah RP, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis: an update on classification, diagnosis, natural history and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012;14:95-105.

19 Kamisawa T, Okazaki K, Kawa S, Shimosegawa T, Tanaka M; Research Committee for Intractable Pancreatic Disease and Japan Pancreas Society. Japanese consensus guidelines for management of autoimmune pancreatitis: III. Treatment and prognosis of AIP. J Gastroenterol 2010;45:471-477.

20 Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K, Nishino T, Watanabe H, Kanno A, et al. Standard steroid treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2009;58:1504-1507.

21 Raina A, Yadav D, Krasinskas AM, McGrath KM, Khalid A, Sanders M, et al. Evaluation and management of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience at a large US center. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2295-2306.

22 Song TJ, Kim MH, Moon SH, Eum JB, Park do H, Lee SS, et al. The combined measurement of total serum IgG and IgG4 may increase diagnostic sensitivity for autoimmune pancreatitis without sacrificing specificity, compared with IgG4 alone. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1655-1660.

23 Kanno A, Ishida K, Hamada S, Fujishima F, Unno J, Kume K, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis by EUSFNA by using a 22-gauge needle based on the International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76: 594-602.

24 Imai K, Matsubayashi H, Fukutomi A, Uesaka K, Sasaki K, Ono H. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy using 22-gauge needle in diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:869-874.

25 Detlefsen S, Mohr Drewes A, Vyberg M, Klöppel G. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis by core needle biopsy: application of six microscopic criteria. Virchows Arch 2009; 454:531-539.

26 Ryu JK, Chung JB, Park SW, Lee JK, Lee KT, Lee WJ, et al. Review of 67 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis in Korea: a multicenter nationwide study. Pancreas 2008;37:377-385.

27 Hart PA, Kamisawa T, Brugge WR, Chung JB, Culver EL, Czakó L, et al. Long-term outcomes of autoimmune pancreatitis: a multicentre, international analysis. Gut 2013;62:1771-1776.

28 Sugumar A. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2012;41:9-22.

Received May 2, 2013

Accepted after revision November 15, 2013

Author Affiliations: Department of Gastroenterology (Xin L, Zhu XF, Hu LH, Zou DW, Jin ZD, Liao Z and Li ZS), Department of Pathology (Chang XJ and Zheng JM), Department of Nuclear Medicine (Zuo CJ), Department of Radiology (Shao CW), and Department of General Surgery (Jin G), Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433, China; Department of Surgical Oncology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China (He YX); Department of General Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China (Zhang QH) Corresponding Author: Prof. Zhao-Shen Li, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, 168 Changhai Road, Shanghai 200433, China (Tel: +86-21-31161335; Fax: +86-21-55621735; Email: zhaoshenli@hotmail.com)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60263-0

Published online May 29, 2014.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- A new approach for Roux-en-Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Surgical treatment of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: an underestimated malignant tumor?

- Comparison of brush and basket cytology in differential diagnosis of bile duct stricture at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- A selective approach to the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients and its outcome

- Effect of the number of positive lymph nodes and lymph node ratio on prognosis of patients after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia arising from an ectopic pancreas in the small bowel