验前概率联合冠脉CT造影对于稳定型冠心病的诊断价值

周 伽,杨俊杰,周 迎,杨晓波,张华巍,陈韵岱

1解放军总医院 心内科,北京 100853;2南开大学医学院,天津 300071

验前概率联合冠脉CT造影对于稳定型冠心病的诊断价值

周 伽1,2,杨俊杰1,周 迎1,杨晓波1,2,张华巍1,陈韵岱1

1解放军总医院 心内科,北京 100853;2南开大学医学院,天津 300071

目的比较升级的Diamond-Forrester法(updated Diamond-Forrester method,UDFM)和Duke临床评分(Duke clinical score,DCS)对于冠心病的评估准确性,并进一步分析验前概率与冠脉CT造影(computed tomographic coronary angiography,CTCA)联合应用的诊断准确性。方法纳入2012年1月- 2013年12月因稳定型心绞痛在解放军总医院心内科先后行CTCA和传统冠状动脉造影(conventional coronary angiography,CCA)的患者523例,分别用UDFM和DCS估算每例患者患冠心病的验前概率。以CCA结果为金标准,分析验前概率、CTCA及两者联合应用对冠心病的诊断准确性。理论验后概率根据贝叶斯公式进行计算。结果523例患者中有385例(74%)CCA结果为阳性。与UDFM相比,DCS将更多的CCA结果阳性患者分入高验前概率组(46% vs 23%,P<0.000 1)。DCS的ROC曲线下面积明显大于UDFM[0.77(0.73,0.82) vs 0.71(0.66,0.77),P=0.000 9]。根据DCS估算结果划分的低、中和高3个验前概率亚组中,CTCA的敏感性、特异性、阳性预测值及阴性预测值分别是94%、98%和97%,94%、87%和55%,91%、94%和93%及96%、96%和77%。中验前概率亚组的理论验后概率十分接近实际验后概率(阳性:94.7% vs 93.6%,阴性:3.7% vs 4.0%)。结论对于稳定型心绞痛患者,DCS比UDFM更适用于冠心病验前概率的估算。将按DCS估算的验前概率与CTCA联合应用,能够有效提高CTCA的诊断准确性,并避免过度检查。

冠心病;冠脉CT造影;验前概率;贝叶斯定理

传统冠状动脉造影(conventional coronary angiography,CCA)是诊断冠心病的金标准,但是作为一种有创检查,其昂贵的费用以及术中、术后并发症不能被忽视。已有多项大型、前瞻性研究证明,以CCA为金标准,冠脉CT造影(computed tomographic coronary angiography,CTCA)具有良好的诊断准确性,特别是近乎100%的阴性预测值,提示CTCA可以作为CCA的无创“看门人”[1-4]。然而,CTCA也有其局限性,如较大的辐射剂量及造影剂的使用可能会对患者造成损害[5],其诊断准确性也受多种因素影响,如心率、体质量及血管的钙化情况[6-7]。具有怎样临床特征的病人最适合进行CTCA检查?目前,在低中患病率人群中,验前概率与CTCA联合应用的临床价值已得到证实[3,8-10]。本实验旨在研究在高患病率人群(如因稳定型心绞痛而进行CCA检查的患者)中验前概率与CTCA诊断准确性是否存在密切联系。我们选择两种应用最广泛的验前概率评估模型,分别是升级的Diamond-Forrester法(updated Diamond-Forrester method,UDFM)[11]和Duke临床评分(Duke clinical score, DCS)[12]。已有多项研究证明,二者在中低患病率人群中具有较高的评估准确性[10-11,13-14],并且在最近发布的多个指南中[15-17],二者也作为评估验前概率的首选模型。我们将探索这两种模型在高患病率人群中联合应用CTCA的临床诊断价值。

对象和方法

1研究对象 本研究共纳入2012年1月- 2013年12月因稳定型心绞痛入我科就诊并于2周内先后行CTCA和CCA的患者523例。排除标准:不稳定型心绞痛和心肌梗死,冠脉的血运重建史(包括冠脉介入治疗和冠脉旁路移植手术),肾功能受损(血清肌酐>120μmol/L),心功能Ⅲ或Ⅳ级(NYHA分级),非窦性心律(房颤和频发性室性早搏等),严重的主动脉疾病以年龄超过90岁。

2患者数据分析 典型的稳定型心绞痛主要有以下3个特征:1)具有特定性质和位置;2)由劳累、体力运动或情绪激动诱发;3)经休息或使用硝酸酯类药物可于数分钟至十数分钟内缓解。如果符合以上3个特征中的2个则定义为不典型心绞痛,符合1个或均不符合则定义为非心绞痛[18]。通过电子病历系统收集患者的相关临床资料,分别根据UFDM和DCS计算每例患者的验前概率并分为低(<30%)、中(30% ~ 70%)和高(>70%) 3组[11-12]。当利用DCS估算验前概率时,>70岁的患者按照70岁(DCS的上限年龄)计算。

3冠脉图像采集分析 所有患者均接受西门子第2代双源CT(Somatom Definition flash)扫描。图像分析由两位有经验的阅片医师(一位放射科医师和一位心内科医师)独立进行,结论不一致时由二者协商决定。所有CCA图像均利用德国西门子数字血管造影机采集,由1名有经验的且对CTCA结果不知情的心内科医师分析。所有患者的冠脉根据最新的分段标准[19]进行分析,直径>1.5 mm的节段按照以下标准进行分类:无狭窄,1% ~ 49%狭窄,>50%狭窄。阳性患者定义为至少有一节段血管狭窄>50%。以CCA为金标准,利用四格表计算CTCA的敏感性(sensitivity,Se)、特异性(specificity,Sp)、阳性预测值(positive predictive value,PPV)、阴性预测值(negative predictive value,NPV)及95%置信区间(confidence interval,CI)。根据贝叶斯公式,验后比=验前比×似然比。

4统计方法 计量资料用或者中位数(25%百分位数-75%百分位数)表示,两组间差异比较用独立样本t检验或Kruskal-Wallis检验。计数资料用频率(百分比)表示,两组之间差异比较用χ2检验或费舍尔精确检验。用Kappa分析评价UDFM和DCS之间的分组一致性。受试者工作特征曲线用来比较两种评估方法的准确性[20]。Mantel-Haenszel检验用来比较不同亚组之间Se、Sp、PPV和NPV的变化趋势。所有统计均由SAS9.2软件完成。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

1基线临床资料 共纳入523例患者,平均年龄61±9岁,58%为男性,52%临床症状表现为典型心绞痛。其中385例CCA结果为阳性,性别、心率、吸烟史、心电图改变和心绞痛类型在两组患者(CCA结果阳性和阴性)中的差异有统计学意义。见表1。

2模型比较 根据UDFM,22%、53%和25%的患者分别被分入低、中和高验前概率亚组,而DCS将更少的病人分入低验前概率组(15%)和中验前概率组(31%)(图1A)。与UDFM相比,DCS将更多的阳性患者分入高验前概率组(46% vs 23%,P<0.000 1)(图1B)。以CCA为金标准,利用ROC曲线比较UDFM和DCS的准确性,得到的DCS的ROC曲线下面积(AUC)明显大于UDFM[0.77(0.73,0.82) vs 0.71(0.66,0.77),P=0.000 9]。

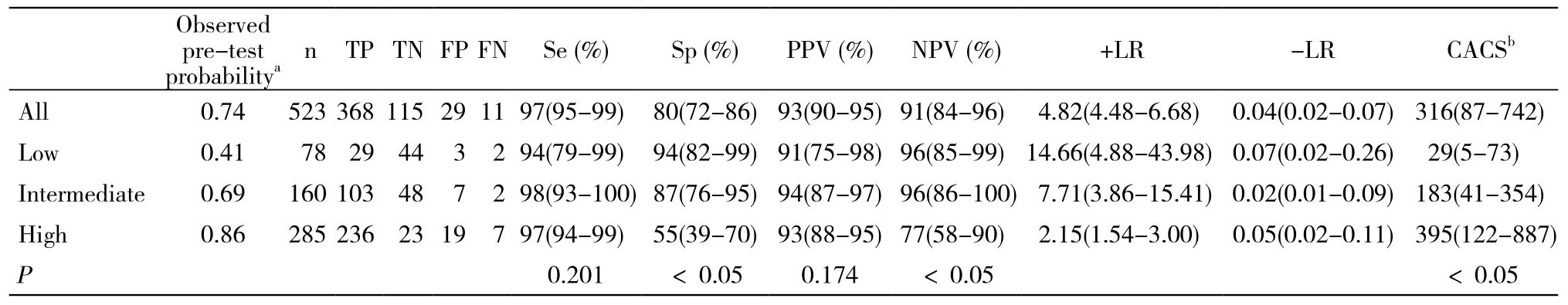

3CTCA诊断准确性分析 以CCA为金标准,CTCA能够准确地诊断出大部分阳性患者(真阳性值=368),这使得CTCA表现出较高的Se(97%,95% ~ 99%)和PPV(93%,90% ~ 95%)。随着验前概率的增加,Sp和NPV都呈现降低的趋势(P<0.05)。见表2。不管是在全部患者中还是在3个不同验前概率亚组中,理论验后概率都很接近实际验后概率,在中验前概率亚组中尤为突出(阳性:94.7% vs 93.6%,阴性:3.7% vs 4.0%)。见表3。

表1 两组稳定型心绞痛患者基线资料比较Tab. 1 Comparison of baseline characteristics of symptomatic patients according to CCA

表2 以CCA为对照分析低、中和高验前概率亚组中CTCA的诊断准确性Tab. 2 Diagnostic accuracy of CTCA in low, intermediate, and high subgroups according to pre-test probability compared with CCA

表3 不同亚组内阴性和阳性CTCA结果对验后概率的影响Tab. 3 Impact of CTCA on post-test probability

图 1 在稳定型心绞痛患者中UDFM和DCS的比较Fig. 1 Comparison of UDFM and DCS in symptomatic patientsA: More than half (53%) of the patients were classified as intermediate pre-test probability group using UDFM, compared with 54% as high using DCS. The bars indicated the 95% CI.aP<0.05, vs UDFM. B: The CCA results revealed that most (74%) of the patients had≥50% stenosis.aP<0.05, vs UDFM

讨 论

作为一种无创影像学检查手段,CTCA的在冠心病诊断中的应用越来越广泛。但如何在实际临床实践中正确使用CTCA仍存在争议。本研究结果证实了在冠心病高发人群中,DCS是一种更准确的验前概率评估方法,并且在验前概率的指导下应用CTCA能够有效提高其诊断准确性,从而避免过度检查。

本研究中,以CCA结果为对照,DCS对验前概率的估算具有较高的准确性。但在另一些研究中,DCS被认为会过高估计验前概率[21-22]。正如Diamond和Kaul[23]所说的“不同的渔网捕到不同的鱼”,验前概率评估模型在不同的研究中表现不同,其原因可能是研究人群之间存在差异。DCS是在一个具有较高患病率(168例患者中有106例CCA结果为阳性)的人群中建立的[12],在患病率较低(23%[21]和31%[22])的研究人群中对DCS进行外部验证,DCS将会过高估计冠心病的患病可能。因此,对于验前概率评估模型的使用,应当注意根据研究人群的临床特点进行谨慎选择。

已有多项研究证明,验前概率可以影响CTCA的诊断准确性[4,17,23]。在我们的研究中,各亚组中不同的Sp和NPV也支持这一观点。我们认为,各亚组假阳性值的不同是引起上述差异的主要原因,而假阳性值主要受冠脉钙化的程度影响。冠脉钙化本身就是一个独立的冠心病危险因素,它与冠心病的验前概率之间存在较强的相关性[24-26],因此高验前概率亚组的平均钙化积分较大;而冠脉钙化引起的高密度伪影会使CTCA过高估计狭窄的严重程度而出现假阳性结果[5-7]。因此在本研究中,高验前概率亚组中出现了更多的假阳性结果。

验前概率能够对CTCA的诊断准确性产生影响,根据贝叶斯定理,它应该是理论验后概率的重要决定因素。在本研究中,各亚组中阳性的CTCA结果都能够将理论验后概率提高到与实际验后概率接近的程度,即阳性的CTCA结果基本可以明确冠心病的存在。但是阴性的CTCA结果在不同的亚组中却有不同的理论验后概率。在中验前概率亚组中,阴性的CTCA结果将理论验后概率降至3.7%,十分接近实际验后概率。因此,对于该类患者,阴性的CTCA结果能够可靠地排除掉患冠心病的可能,不必进行进一步的检查。但是在低验前概率亚组中,阴性的CTCA结果仅将理论验后概率降至7.9%,远大于实际验后概率,这表明即使CTCA得到了一个阴性的结果,仍不能完全排除冠心病的存在,需要更为精准的进一步检查。在高验前概率亚组中,阴性CTCA结果对应的理论验后概率为21%,临床诊断价值更小。根据贝叶斯定理,除了各亚组之间验前概率的差异,较高的阴性似然比(negative likelihood ratio,-LR)是得到较高理论验后概率的重要原因。-LR是反映一项检查诊断准确性的重要指标,-LR越低说明诊断准确性越高。因此,在高验前概率亚组中,诊断准确性受冠脉钙化的影响,CTCA表现出一个较高的-LR是不难理解的。但是低验前概率亚组中CTCA的-LR仍然较高,这可能与本研究入选人群和样本量限制有一定关系,需要进一步的研究进行验证。

本研究的局限性:1)本研究是一个单中心回顾性研究,不可避免地存在选择偏倚。因此,下一步应当进行多中心、前瞻性和大样本量的研究以获得更有说服力的结论。2)冠脉狭窄程度仅通过肉眼观察重建图像来判定,诊断结果存在观察者间的差异[27]。但是通过运用多种图像重建技术以及安排2名以上医师进行互盲的分析诊断,这种变异对研究结果的影响已被降至最低。3)受到各种因素(尤其是钙化斑块)的影响,一部分冠脉节段存在严重的伪影,致使管腔狭窄程度评估受限。我们采取的策略是将所有无法评估狭窄程度的节段都按狭窄>50%记录,因为在实际临床实践中对于阳性或者无法评估的冠脉节段,往往都需要进行进一步的检查。这种策略使得本研究中有关CTCA诊断准确性的各项指标能更真实地反映临床实际情况。

总而言之,我们的研究表明,在因稳定型心绞痛而住院的患者中,按DCS估算具有中验前概率(30% ~ 70%)的患者进行CTCA检查获益更大。对于此类患者,阴性的CTCA结果能可靠地排除患病可能,从而可以有效避免过度检查。

1 Arbab-Zadeh A, Hoe J. Quantification of coronary arterial stenoses by multidetector CT angiography in comparison with conventional angiography methods, caveats, and implicationsp[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2011, 4(2):191-202.

2 Alani A, Nakanishi R, Budoff MJ. Recent improvement in coronary computed tomography angiography diagnostic accuracy[J]. Clin Cardiol, 2014, 37(7): 428-433.

3 Van Werkhoven JM, Heijenbrok MW, Schuijf JD, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice multislice computed tomographic coronary angiography in patients with an intermediate pretest likelihood for coronary artery disease[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2010, 105(3):302-305.

4 Gueret P, Deux JF, Bonello L, et al. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography coronary angiography (from the Prospective National Multicenter Multivendor EVASCAN Study)[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2013, 111(4):471-478.

5 Prat-Gonzalez S, Sanz J, Garcia MJ. Cardiac CT: indications and limitations[J]. J Nucl Med Technol, 2008, 36(1): 18-24.

6 Kruk M, Noll D, Achenbach S, et al. Impact of coronary artery Calcium characteristics on accuracy of CT angiography[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2014, 7(1): 49-58.

7 Voros S. What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of volumetric CT scanning?[J]. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2009,3(2):67-70.

8 Cheneau E, Vandat B, Bernard L, et al. Routine use of coronary computed tomography as initial, diagnostic test for angina pectoris[J]. Arch Cardiovasc Dis, 2011, 104(1): 29-34.

9 Meijboom WB, Van Mieghem CA, Mollet NR, et al. 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with high,intermediate, or low pretest probability of significant coronary artery disease[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007, 50(15):1469-1475.

10 Wasfy MM, Brady TJ, Abbara S, et al. Comparison of the Diamond-Forrester method and Duke Clinical Score to predict obstructive coronary artery disease by computed tomographic angiography[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2012, 109(7):998-1004.

11 Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, et al. A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation,updating, and extension[J]. Eur Heart J, 2011, 32(11): 1316-1330.

12 Pryor DB, Shaw L, Mccants CB, et al. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease[J]. Ann Intern Med, 1993, 118(2): 81-90.

13 Jensen JM, Voss M, Hansen VB, et al. Risk stratification of patients suspected of coronary artery disease: Comparison of five different models[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2012, 220(2): 557-562.

14 Jensen JM, Ovrehus KA, Nielsen LH, et al. Paradigm of pretest risk stratification before coronary computed tomography[J]. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2009, 3(6):386-391.

15 Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, et al. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/ HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America,Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography,Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014, 63(4):380-406.

16 Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/ PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease a report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines, and the American college of physicians,American association for thoracic surgery, preventive cardiovascular nurses association, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, and society of thoracic surgeons[J]. Circulation,2012, 126(25): E354-U191.

17 Task Force Members, Montalescot G, Sechtem U, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology[J]. Eur Heart J, 2013, 34(38):2949-3003.

18 Somerville W. Tetralogy versus tetrad and a wish for the new journal[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1983, 1(2): 574.

19 Raff GL, Abidov A, Achenbach S, et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary computed tomographic angiography[J]. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2009, 3(2):122-136.

20 Hanley JA, Mcneil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve[J]. Radiology,1982, 143(1): 29-36.

21 Kumamaru KK, Arai T, Morita H, et al. Overestimation of pretest probability of coronary artery disease by Duke clinical score in patients undergoing coronary CT angiography in a Japanese population[J]. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2014, 8(3):198-204.

22 Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG, et al. Prediction model to estimate presence of coronary artery disease: retrospective pooled analysis of existing cohorts[J]. BMJ, 2012, 344:e3485.

23 Diamond GA, Kaul S. Gone fishing!: on the “real-world” accuracy of computed tomographic coronary angiography: Comment on the“Ontario multidetector computed tomographic coronary angiography study”[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2011, 171(11):1029-1031.

24 Rozanski A, Gransar H, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of coronary artery Calcium scanning on coronary risk factors and downstream testing the EISNER (Early Identification of Subclinical Atherosclerosis by Noninvasive Imaging Research) prospective randomized trial[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011, 57(15): 1622-1632.

25 Elias-Smale SE, Proença RV, Koller MT, et al. Coronary Calcium score improves classification of coronary heart disease risk in the elderly: the Rotterdam study[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010, 56(17):1407-1414.

26 Madhavan MV, Tarigopula M, Mintz GS, et al. Coronary artery calcification: pathogenesis and prognostic implications[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014, 63(17):1703-1714.

27 Choudhary G, Atalay MK, Ritter N, et al. Interobserver reliability in the assessment of coronary stenoses by multidetector computed tomography[J]. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 2011, 35(1): 126-134.

Diagnostic accuracy of pre-test probability combined with computed tomographic coronary angiography in patients suspected for stable coronary artery disease

ZHOU Jia1,2, YANG Junjie1, ZHOU Ying1, YANG Xiaobo1,2, ZHANG Huawei1, CHEN Yundai1

1Department of Cardiology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China;2School of Medicine, Nankai University, Tianjin 300071, China

CHEN Yundai. Email: cyundai@medmail.com.cn

ObjectiveTo compare the performance of updated Diamond-Forrester method (UDFM) and Duke clinical score (DCS) in patients with stable angina pectoris and assess the combined application of pre-test probability and computed tomographic coronary angiography (CTCA) in these patients.MethodsFive hundred and twenty-three symptomatic patients who underwent both CTCA and conventional coronary angiography (CCA) in 2 weeks in Chinese PLA General Hospital from January 2012 to December 2013 were enrolled in this study. The pre-test probability was determined using UDFM and DCS for each patient. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were used to compare two models. The diagnostic accuracy of CTCA for detecting coronary artery disease (CAD) was compared with CCA. The estimated post-test probability was calculated by Bayesian statistics.ResultsOf the 523 patients, 385 (74%) were positive tested by CCA. Compared with UDFM, DCS reclassified more positive patients into high group (46% for DCS vs. 23% for UDFM, P<0.000 1). The areas under ROC curves (AUC) for DCS was significantly greater than that for UDFM [0.77 (0.73, 0.82) vs 0.71 (0.66, 0.77), P=0.000 9]. In patient-based evaluation by CTCA, three pre-test probability groups according to DCS revealed a sensitivity of 94%, 98% and 97%, a specificity of 94%, 87% and 55%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 91%, 94% and 93%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96%, 96% and 77%, respectively. The estimated post-test probabilities corresponded well with the observed one, especially for the intermediate estimated pre-test probability group (positive: 94.7% vs 93.6%, negative: 3.7% vs 4.0%).ConclusionCompared with UDFM, DCS has a better performance in calculating pretest probabilities in patients with stable angina pectoris. In addition, the combined application of DCS and CTCA can avoid unnecessary tests.

coronary disease; coronary computed tomographic angiography; pre-test probability; Bayesian theorem

R 814.42

A

2095-5227(2015)04-0313-05

10.3969/j.issn.2095-5227.2015.04.004

时间:2015-01-04 11:33

http://www.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3275.R.20150104.1332.006.html

2014-09-23

北京市科委首都临床特色应用研究(Z141107002514103)

Supported by the Study on the Application of Capital, Clinical Characteristics(Z141107002514103)

周伽,男,在读硕士。研究方向:冠脉CT的临床应用。Email: zhoujiasirius@126.com

陈韵岱,女,主任医师,主任,博士生导师。Email: cy undai@medmail.com.cn